Book Review: The Leonard Bernstein Correspondence — A Tour of Twentieth Century Cultural History

By Helen Epstein

So is the book worth reading? Depends how interested you are in twentieth century cultural history, in music and creative genius, in marriage and sexuality, in what people allow themselves to be conscious of and what they block out.

The Leonard Bernstein Letters, edited by by Nigel Simeone. Yale University Press, 606 pages, $38.

Reading this correspondence between twentieth century musical genius Leonard Bernstein and his many friends feels like legitimized voyeurism to me, even if most of it was written decades ago. It embodies sixty years of American cultural history around a complex and controversial man torn between conflicting loyalties to career, family, ambition, politics, and sexuality, and his wife, lovers, collaborators and friends.

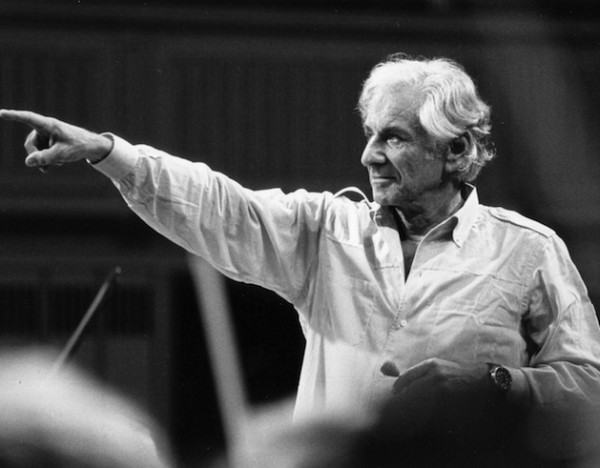

I grew up in Manhattan in the 1950s and ’60s, when Bernstein was the local hero. Handsome, articulate, exciting – he dazzled us kids when he conducted his Young People’s Concerts in the afternoons and dazzled the adults with his podium acrobatics at night. Though born in Lawrence, Massachusetts (in 1918) and educated at Boston Latin and Harvard, he quickly became identified with New York.

His Jewish identity and the anti-semitism he faced in Boston had a lot to do with that, as did the opportunities NYC offered. He arrived in 1939 and by 1943, became part of a coterie of theater collaborators including choreographer Jerome Robbins and lyricists Betty Comden and Adolf Green and garnered an appointment as Assistant Conductor of the New York Philharmonic. That fall of 1943, at the last minute, he replaced an ailing Bruno Walter at a concert and –- aged 25 –made the front page of the New York Times.

Europeans were soon raving about this rare American pianist/conductor in what was then a largely Eurocentric classical music culture. Jews noted that he hadn’t changed his name like so many other performers of that time. Lenny conducted orchestras at La Scala and in Vienna, but also in a DP camp for Holocaust survivors, and in the newly-declared state of Israel during the 1948 war. In the United States, his televised appearances on the national CBS Omnibus series, established him as music professor to the nation, who lectured in plain English but with the inside knowledge of a composer. And who, seemingly on the side, was producing a string of masterpieces for theater, ballet, and the movies — Fancy Free, On the Town, Candide, West Side Story, On the Waterfront.

His personal life was as frenetic as his professional one. In his teens and twenties, Bernstein had many male lovers but, the year he turned 33, he decided to marry the Chilean-born actress Felicia Montealegre whom he met through Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau. He became the father of three children with an ever-more complicated set of relationships and lives.

By 1981, when I was writing about his conducting seminar at Tanglewood for the Sunday New York Times, I met a ribald, paunchy middle-aged man who acted like a teenager. He had turned 63 that summer, his wife had died of cancer, his children were grown, and Lenny was driving around the Berkshires in his beige Mercedes convertible festooned with ornamental young men.

My editors wanted me to get him to talk about his homosexuality – still news for some people in 1981. I wanted to know more about the roots of his extraordinary energy and productivity as pianist, conductor, composer, teacher — and his almost religious ability to inspire people. In our interview (published in the Soho Weekly News), he talked about his parents, the 1930s in Boston, teaching, and the ruinous impact of technology on American culture, quoting entire paragraphs of books he loved by heart (Moby Dick was one). One of the Tanglewood students I interviewed said, “He makes me remember why I wanted to become a musician.” I thought: he makes me remember why I want to be a writer.

So I was very interested in this collection of letters. Biographies and memoirs of Bernstein — there have been many — don’t encompass his infinite variety. I thought a large chorus of narrators might, but I discovered that the curator/editor can shape the record of a life as powerfully as a biographer.

Leonard Bernstein’s correspondence was so wide-ranging that several very different collections could be culled from it. Nigel Simeone (a British musicologist and author of Leonard Bernstein: West Side Story) explains that the 650 letters published in his annotated collection are but a tiny fraction of roughly 10,000 Bernstein wrote and received. Some excerpts have been previously published, but some appear here for the first time and have a cumulative effect. “You save every scrap of correspondence,” one of his longest correspondents, lyricist Betty Comden notes, “from Koussevitzky’s pages on life, music, and your career – to Auntie Clara’s hot denunciations of meat.”

Leonard Bernstein with schoolchildren in the 1950s. The author thinks she is the girl second from the right.

Simeone organizes the letters into eight roughly chronological sections, each preceded by a short introduction. The first is written by a 14-year-old Lenny to Helen Coates, his piano teacher from 1932 until 1935 and secretary from 1944 to 1989. The last – four days before his death in October of 1990 — is from fellow conductor Georg Solti (originally Stern), a Hungarian Jew who, in the 1950s, advises him on relations with Viennese Philharmonic members who were Nazis during the war. In between are relatively superficial letters from Bernstein and some startlingly profound and insightful ones from his correspondents.

In the early letters, Bernstein seems no different from other ambitious, self-absorbed and self-dramatizing young men of his time. “God damn it Aaron, Why practice Chopin Mazurkas? Why practice even the Copland Variations?” he writes to Aaron Copland in one of the few letters included that describe world events. “The week has made me so sick, Aaron…With millions of people going mad — madder every day because of a most mad man strutting across borders – with every element that we thought had refined human living and made what we called civilization being actively forgotten….what chance is there?”

Yet in Simeone’s selection of letters, there is no indication that Bernstein ever thought seriously of fighting the Nazis. Several of his friends did and other musicians seem far more plugged into reality. “Nice that you’ve been able to finish pieces in these troublous times. (I haven’t been able to do much more than read newspapers),” Copland wrote Bernstein in August of 1939. After the fall of France in 1940, Bernstein writes to composer David Diamond that a friend is “terribly upset about France, more than all of us, because her home town and mother are involved. A ghastly business.”

I was particularly struck by letters after American entry to the war, when the young Bernstein, Robbins, and Adolf Green went about their work in a creative bubble while the second world war disrupted other people’s lives. On the Town is about sailors on a 24-hour furlough in New York, but unlike many of his peers Bernstein (at least as evidenced in this collection of letters) seemed never to have considered joining the military. He expresses sympathy when friends are drafted. When called before an army medical board for the first time in the fall of 1941, he writes to Copland: “God, I have a lucky star! Not so much the asthma either (tho that was the legal excuse) as the fact that the particular doctor who examined me insisted on preserving the cultural foundation of the USA, not killing all the musicians. And so I am in class IV. Go, attend to your career, said the great M.D. and that will be yr greatest service. Osanna in excelsis!”

Two years later, in September of 1943, two years after his first draft examination and after several of his friends were shipped overseas, he writes to Koussevitzky, “An amazing thing has happened! Thursday night I was deferred for all time from the army….I am happy to say that because of the spirit of the Medical Board I feel no guilt whatsoever at my deferment.”

Perhaps he discussed his reasons in other letters or talked about them in psychoanalysis (there is a letter from his analyst after the end of the war inquiring “How do you feel about the Peace?”). The main item on his analytic agenda, however, seems to have been his intimate life. He and clarinetist David Oppenheim shared New York analyst Marketa Morris, whom they called “The Frau” and with whom Lenny worked for at least five years. In 1942, he wrote to Copland that “The Frau sessions have borne some fruit. Little green fruit, of course, but fruit. The main thing being that I can’t kid myself anymore. Kid myself, that is, into thinking that I have a closeness with someone when it is all really wishful thinking, or induced, or imagined, or escape from being alone with myself, etc….and then this wish for closeness always manifests itself in a sexual desire, the more promiscuous the better – giving rise to experiences like being taken (by pfb – Paul Bowles –) to a Bain Turc (or is it Turque?) and seeking out the 8th street bars again.”

Such letters are not numerous in this collection, perhaps because Copland and Bernstein were all too aware of their destructive potential both at the time and in the future. The mentor notes “Dear Pupil, What terrifying letters you write: fit for the flames is what they are. Just imagine how much you would have to pay to retrieve such a letter forty years from now when you are conductor of the Philharmonic… I mustn’t forget to burn them.”

Copland is the only correspondent to whom Bernstein confides the entirety of his personal and professional life. He censors and compartmentalizes when he corresponds with mentors Dimitri Mitropolou and Serge Koussevitzsky; collaborators Marc Blitzstein, Robbins, Comden and Green, Lillian Hellman, Arthur Laurents; composer colleagues David Diamond, William Schuman (later Poulenc, Milhaud, Messaien, and Stockhausen); his family and friends.

His classmates and friends are usually far more interesting and insightful, if sometimes brutal. “As an honest human being and a conscientious composer it would seem that you should not be satisfied with your music until it has a little bit of the real Lenny in it—and not just a rehash of Hindemith and Copland,” writes Shirley Gabis, one of the many female letter writers in this collection, after she hears a recording of his Clarinet Sonata in 1944. “And Lenny, believe me when I tell you that although you are headed for a brilliant career, it will never be a great one. Your driving ambition to be the most versatile creature on earth will kill any possibility of you becoming a truly great artist in any one of the talents you possess…and don’t write clarinet sonatas that make any serious musician think you an utter fool – it’s not fair to yourself because you’re not really an utter fool.”

Bernstein had other startlingly candid female correspondents. His secretary Helen Coates was one. The journalist Martha Gelhorn whom Bernstein met in Cuernava was another. Comparing Bernstein to her ex-husband Hemingway in 1959, she writes that he “was interested in everyone but there was a bad side. It was like flirting. Like you, in fact, he has the excessive need to be loved by everyone, and specially by all the strange passing people whom he ensnares with that interest, as you do with your charm, though in fact he didn’t give a fart for them.”

But Bernstein’s most intimate relationships with women were with his wife Felicia and his younger sister Shirley. “Sweedie,” reads a typical letter from Israel:

I arrived in Jewland yesterday, a hulk of a once proud ship, ridden with intestinal bugs of some sort. The three weeks in Italy were screaming successes, but a nightmare of impossible schedules, cold rainy weather and diarrhea…How strange that you should have written just now of Felicia! Ever since I left America she has occupied my thoughts uninterruptedly, and I have come to a fabulously clear realization of what she means – and has always meant – to me. I have loved her, despite all the blocks that have consistently impaired my loving-mechanism, truly & deeply from the first. Lonely on the sea, my thoughts were only of her. Other girls (and/or boys) meant nothing. Even the automatic straining toward general sexuality of the moment –which had always carried a big stIck with me , was of no importance. I have been consistently aware of the great companionship of this girl…I’ve never felt so strongly as these weeks in Italy how through I am with the conductor-performer life (except where it really matters) and how ready I am for inner living, which means composing and Felicia.

A few days later Bernstein writes from Tel Aviv:

Shalom Shvestoah…I have been engaged in an imaginary life with Felicia, having her by my side at the beach as a shockingly beautiful Yemenite boy passes –inquiring into that automatic little demon who always springs into action at such moments –then testing: if Felicia were there..But now I feel such a certainty about us – I know there’s a real future involving a great comradeship, a house, children, travel, sharing, and such a tenderness as I have rarely felt…

The Bernstein-Montealegre correspondence reproduced in this collection is bland by comparison, except for an early and remarkable statement of resolve from his wife, 30-year-old Felicia:

Darling, If I seemed sad as you drove away today it was not because I felt in any way deserted but because I was left alone to face myself and this whole bloody mess which is our ‘connubial’ life… First: we are not committed to a life sentence –nothing is really irrevocable, not even marriage (though I used to think so. Second: you are a homosexual and may never change – you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? Third: I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the L.B. altar. (I happen to love you very much – this may be a disease and if it is, what better cure?).

If the drama of Bernstein’s private life was not tense enough at this time, he is also contending with the blacklist. In June of 1950, his name had appeared in Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, a “resource” for employers that named 151 actors, writers, and musicians as politically subversive. Vacationing in Cuernavaca, Mexico, he met several victims of the blacklist, including Academy Award-winning film director Robert Rossen. “He is lonely and restless and beset with all the problems of a martyr and hero without being either of them,” he writes his sister in May of 1951:

He is wretchedly lost, having lost Hollywood, and makes braver speeches than he feels. I think he may go back and face the Committee next week…He feels finished in the States. It’s a mess, and I am so sorry for him. It can also happen to all of us, so we better start preparing our blazing orations now. Maltz is also living here (Cuernavaca has become a great haven for these poor guys)…Dimitryk has certainly made a ghoul of himself: and the boy in the biggest jam right now seems to be Garfield. He will wind up in a great perjury mess if he doesn’t watch out. It may already be too late. Actually, I suppose, there is nothing to be done when your life and career are attacked but strike back with the truth and go honestly to jail if you have to. This dandling about to save a career can neither save the career nor make for self-respect. I hope I am as brave as I sound from this distance when it catches up with me.

Bernstein was nowhere close to brave when it caught up with him. He wasn’t subpoenaed by the HUAC, but when he submitted his passport for renewal in April of 1953, he heard nothing back. The composer knew exactly what that meant. Composer Marc Blitzstein was his long-time friend and his new-born daughter’s godfather; Bernstein had produced his radical musical The Cradle will Rock as a Harvard undergrad. Colleagues, including internationally-acclaimed performer Paul Robeson’s career had all but come to an end when, two years earlier, the State Department refused to renew Robeson’s passport (as per a 1950 law limiting issuance of passports to “persons supporting the Communist movement”) unless he signed a loyalty oath to the United States and disavowed Communism. Robeson refused, and engaged in a legal battle that would drag on until 1958. Bernstein sought legal counsel and, in August of 1953, did what Robeson would not: he went to Washington, and filed an affidavit of disavowal.

The tone of that affidavit (which Simeone includes in its 3000-word entirety) is markedly different from Bernstein’s even most formal letters and was probably doctored by lawyers. The 35-year-old wunderkind postures and grovels, portraying himself as a head-in-the-clouds artiste, unaware of politics. Compared to what we have learned since about other responses — Arthur Miller also had his passport withheld for a time – Bernstein’s affidavit makes for very uncomfortable reading beyond the standard formula:

Although I have never, to my knowledge, been accused of being a member of the Communist Party, I wish to take advantage of this opportunity to affirm under oath that I am not now nor at any time have ever been a member of the Communist Party or the Communist Political Association…

He described his connections to organizations deemed subversive by the Attorney General, as

of a most casual and nebulous character. Almost without exception, their very names are practically unknown by me except in the vaguest kind of way. In fact, in now attempting to recall them and my connection with them, I have had to rely on the memory of my secretary…I never could claim any exact knowledge as to their objectives or purpose except the humanitarian, benign or cultural one mentioned at the moment I was accosted by some person or scanned the letter or other sugar-coated communication soliciting funds, the use of my name or my services as a musician and conductor….

Like almost every other person who has achieved some prominence, I have received hundreds and perhaps thousands of letters in the past ten years soliciting my assistance in one form or another…Those asking for the use of my name as a sponsor would usually be accepted on the basis of the prominence of the person soliciting me or the fact that other well known persons, not known by me to be suspect, had previously agreed to the use of their own names. The fallacy of this procedure in evaluating an organization has been demonstrated in too many cases…

Bernstein then enumerates various organizations with which his name has been linked – the American Committee of Yugoslav Relief, the National Negro Congress, the American Committee for Spanish Freedom, the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade – about which he claims to know nothing. In the last case he writes, “I believe that Paul Robeson communicated with me about the use of my name on this occasion. I met Mr. Robeson one time while we were both backstage during a concert.”

This nadir in Bernstein’s life has been described by Barry Seldes in his 2009 book Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician. Paul Robeson is the only name he names, but it still makes for dispiriting reading. Bernstein, a gay man when that was a serious professional liability, a Jew when anti-semitism was rampant, and a “progressive” with many friends who were Party members, must have known that the FBI was trailing him. In a 2009 New Yorker piece, Alex Ross writes that Bernstein’s FBI file is 800 pages long. Some of Bernstein’s closest artistic collaborators – the On the Waterfront trio Elia Kazan, Jerome Robbins and Lee J. Cobb, for example – named names but many others – including his beloved (gay) mentor Aaron Copland – did not.

After the ordeal was over, in a letter to his younger brother Burton, Bernstein wrote only that he had been “insanely lucky” to obtain the legal services of “Jim McInerney, formerly head of Criminal Investigation in the Dept of Justice – an old Commie chaser – just the right person to have on my side. It was worth the whole ghastly and humiliating experience just to know him, as well as the $3500 fee. Yes, that’s what it costs these days to be a free American citizen.”

Bernstein’s affidavit not only secured his ability to meet his international engagements but paved the way for the first step of his television career (starting with musical lecture-demonstrations on the CBS program Omnibus in 1954) and his eventual appointment as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic. Five days after Bernstein got his new passport, he wrote composer David Diamond that he was at Tanglewood between finishing up a Brandeis music festival and taking off to conduct in Brazil, Israel, and Italy: “Very hard to know how to balance one’s life & work.”

The rest of the collection documents that exhausting balancing act.

Simeone includes correspondence from all the competing people who claimed his attention: family members including his parents; impatient and often disappointed collaborators such as Marc Blitzstein (Threepenny Opera and Regina) Lillian Hellman (Candide), Betty Comden (Wonderful Town); Arthur Laurents, Jerome Robbins, and Stephen Sondheim, who would work on West Side Story for nearly eight years. Simeone devotes too many pages to this and to the development of the Chichester Psalms. More interesting are the many letters from anxious contemporary composers – Poulenc, Milhaud, Messaien, Cage, Carter, Stockhausen, William Schuman, Gunther Schuller –who argue with Bernstein about his musical choices or instruct him on how to conduct their music according to their precise guidelines and with the musicians they favor.

There’s an overabundance of lovey-dovey letters between Bernstein and his wife Felicia Montealegre while they are courting and married; none foreshadow their bitter separation in 1976 aside from an oblique reference in a New Year’s card to Bernstein’s secretary Helen Coates: “At this very crucial turning point in both our lives my annual wishes for a happy new year carry very special weight.”

The collection begs other questions. Simeone includes some missives responding to letters not in the edition and others posing questions that raise our interest in a response. The editor does his best to fill in the blanks with introductions to each section and he refers readers to the many excellent Bernstein biographies and memoirs by many of the letter writers themselves. But it’s insufficient. Just reading the letters becomes exhausting. The number of correspondents keeps growing: Bernstein’s creative output – Mass, Songfest, the ballet Dybbuk, and the musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue with Alan Jay Lerner, the opera A Quiet Place – continues unabated, despite negative or indifferent critics, as does his conducting and teaching.

So is the book worth reading? Depends how interested you are in twentieth century cultural history, in music and creative genius, in marriage and sexuality, in what people allow themselves to be conscious of and what they block out. One of the most elegant and empathic letters in the collection is from fellow pianist/conductor/composer Andre Previn, who performed with Bernstein on the latter’s 60th birthday and was alarmed by his state of mind:

I’ve been an admirer and follower and, in a more remote way, a disciple since I first heard you make music in San Francisco in 1950 with the Israel Philharmonic. You’ve touched, directly or circuitously, a great many musical decisions of mine, but what’s more important, the lives and ambitions of every conductor in this country…Therefore, if you were to succumb to a depression, however temporary, that would keep you from your usual frighteningly energetic achievements, you’d be letting down an amazing number of musicians. You’ve kept those of us who grew up in the same years as you feeling young; you’ve kept those older than you correctly infuriated; and you’ve been a lighthouse of constancy to all those 20-year-old current phenomena. As a friend, I can see that this is a burden you might not want right now, but as a member of that weird band who feel that a day without music is an irresponsible waste, I have to tell you that you’re stuck with it…

I recently saw a screening of re-mastered print of West Side Story in the Shed at Tanglewood, where Bernstein spent some of his happiest summers, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra providing musical accompaniment. It was a stunning experience and one whose memory seems to incorporate all the many disparate angles in this collection of letters. Imperfect as the selection may be, it offers up a vivid portrait in the words of people who believed, like Martha Gelhorn, “What I write you here is, as you can understand, secret and between us only and forever.”

Hear Leonard Bernstein’s daughter Jamie talk about the letters.

Authors of Leonard Bernstein biographies include: Burton Bernstein, Joan Peyser, Meryle Secrest, Humphrey Burton, Barry Seldes, John Gruen, Schuyler Chapin. Jack Gottlieb, Jonathan Cott.

Helen Epstein spent a summer interviewing and observing Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood in 1981. Her profile “Listening to Lenny” appears in Music Talks from Plunkett Lake Press.

Tagged: Culture Vulture, Nigel Simeone, The Leonard Bernstein Letters