Visual Arts Review: “Dilated Biography — Contemporary Cuban Narratives”

LCurator Jorge Antonio Fernández succeeds, for the most part, in creating a stimulating show that is held together by formal and conceptual associations, not just political concerns.

Dilated Biography: Contemporary Cuban Narratives at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (SMFA), Boston, MA, through October 19th.

By Kevin Hong

Curator Jorge Antonio Fernández Torres has organized a tight, two-room show at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, around the concept of the “dilated biography,” a term inspired by Cuban artist Severo Sarduy. According to Sarduy, one’s biography occurs before birth, and throughout life it expands or dilates. There is a structuralist flavor to this claim that Torres picks up on and uses to approach works of art, which have lives of their own. He writes, “They have started out from a code, a sort of index where individuality also constructs fiction and creates its own invention.” The form and content of works of art, like ourselves, are to some extent predetermined by the deeply-engrained cultural practices that precede them. But the “dilation” that follows a creative act denotes the complication and extension of meaning that occurs when a work of art leaves the artist’s studio and comes into contact with the world. Every point of connection between the piece and some other entity — viewer, gallery space, another work — elaborates its significance.

This connectivity is paramount to Torres and his show, which brings together fifteen Cuban artists in an attempt to represent the diversity of Cuban identity. As the curator writes, “Cuba is, was, and always will be a trans-territorial space of mutations, identities and expansions.” More specifically, the exhibition “is not limited to a region or age group, nor does it emphasize any particular style or method. The only discernible common factor lies in the individual poetics.” With a small space and nineteen pieces of art, the curator’s job, which has always consisted in directing physical and intellectual traffic, is complicated by the task of making incredibly different kinds of art hang together. He is further challenged by the fact that many of the works’ nuances will be lost on its American audience. Torres is sensitive to these problems, and he succeeds, for the most part, in creating a stimulating show that is held together by formal and conceptual associations, not by historical or political connotations. “Curatorial decisions are not to be regarded as attempts to make the exhibition more understandable,” Torres writes. Rather, “Our purpose here is to … look for the infinite number of meanings to activate the idea as a visual resource.”

Of the works in the first half of Dilated Biography, Wildredo Prieto’s “Politically Correct” is the smallest and perhaps the most radical. A viewer may not even notice the watermelon cube, which sits unobtrusively on the carpeted floor, but upon closer notice, one discovers that the red flesh of the watermelon is crawling with fruit flies.”Politically Correct” presents the watermelon at its least melon-y: its green rind has been reduced to a thin support, its roundness has been supplanted by a geometric order, and it has been placed in front of an audience for the purpose of optic, not gastric, consumption. One realizes that only the fruit flies, unaware of the social or political orders that govern human and artistic behavior, deal with the object as it is meant to be dealt with. Prieto ridicules the arbitrary rules that direct our interactions, thereby opening up possibilities for different kinds of creative engagement.

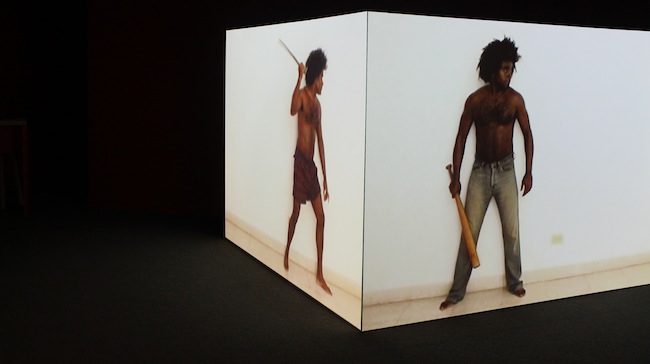

A larger work across the room echoes the strict geometry of Prieto’s cube. This one glows: Alexandre Arrechea’s “White Corner” is an installation that involves two walls and a double projection. The walls come together to form a corner, and each projection is a video of Arrechea himself — in one, projected on the left wall, he holds a machete, and in another, shown on the right wall, he holds a baseball bat. The two bare-chested Arrecheas edge toward each other, then edge away; each senses the other’s unnerving presence around the corner. At times Arrechea will raise his machete, and at times Arrechea will ready his bat. Neither ever strikes, too afraid to encounter the enemy. In “White Corner,” Arrechea turns himself into the Other; each of his characters “project” a personality and ideology onto the other. The viewer, standing on one side of the wall, experiences one Arrechea’s fear as he advances toward his object of hatred. Standing back, though, the viewer sees two projections of characters approaching each other — characters that look surprisingly similar.

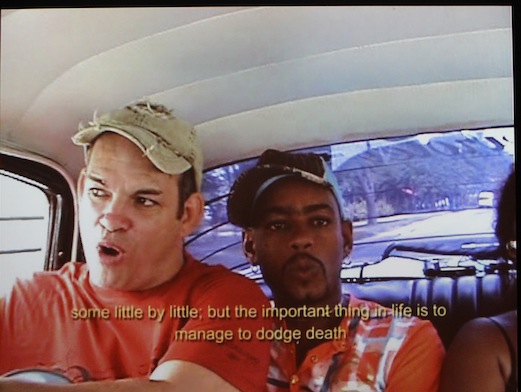

More generally, Prieto’s and Arrechea’s work represent two different forms of connection. The fruit flies’ haphazard flight paths intersect with one another, all converging on the watermelon cube in a sort of microcosm of human activity; “White Corner” dramatizes a single point of encounter which comes to stand for a larger struggle. The first work in the second half of Dilated Biography offers a touching synthesis of these interactions. “Possible Destinations” by Luis Gárciga is a video in which the artist drives a taxi, conveying passengers to their destinations along the streets of Havana. Gárciga offers free transportation in exchange for an answer to the questions: “Where would you like to get in life? Where would you like to get?” The camera focuses only on the passengers, capturing a wide range of responses that highlight the diversity of Cuban identity. Like Prieto’s aleatory flies, each traveler is picked up by chance and also has his or her own practical destination, which the viewer never sees or hears about. But what one hears from the passengers is so personal and thoughtful that one feels emotionally connected to them. “My destination is the spiritual,” one says. “I don’t have a fixed course,” says another, “I don’t know where I’m going.” The travelers sketch out individual biographies which, together, form a larger narrative for Cuba itself.

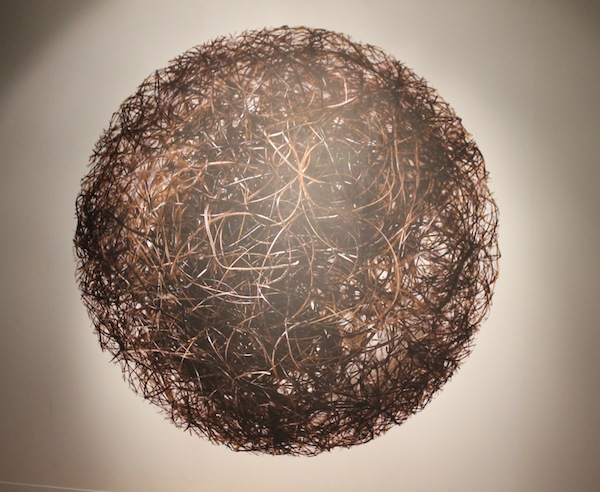

While Luis Gárgica’s video piece documents the aspirations of Cuba’s denizens, Tony Labat’s “Hairball (Pendejo)” presents a dramatically different record of the individual. The work consists of a digital wallpaper print of a perfect sphere of pubic hair, enlarged to take up an entire wall. The hair, which appears to have been carefully gathered and arranged, is not a verbal biography but a physical archive, a manifestation of a period of a human life. On one hand, Labat romantically mythologizes the minute details (vulgarities, one could argue) of one’s existence. The twining of the hair also indicates the complexity and profundity of individual experience, a theme central to all the other works discussed. Seen differently, the whole notion of biography is questioned and ridiculed. While the viewer has some sense of the depth of this “pubic sphere,” the two-dimensionality of the digital print and the wall destroy the illusion. It is impossible to truly gain access to any representation of individuality, especially since what the viewer is looking at is so absurdly insignificant. In this case, the romanticizing viewer is truly the pendejo, seduced by a sentimental reading of the work, or perhaps unwilling to see the truth.

If Labat’s work refuses the viewer’s entry into its interiority, Torres’s work as a curator does the opposite. These carefully selected works (many more of which have not been mentioned) rub together in surprising ways, stimulating ideas that have been lying dormant. Ultimately, at least for American viewers, this exhibition is less about Cuba than it is about different ways to approach “individual poetics”; knowledge of Cuban history or contemporary politics is completely unnecessary to appreciate the voices that have been brought together. If anything, Torres invites you to add your own voice to the mix, a mix which he has described as highly conflicted, one which nevertheless “represents the coexistence of different memories.” This includes your own: such is the process of biographical dilation.

Works discussed:

Politically Correct, Wilfredo Prieto, 2009

Watermelon cube, dimensions variable

White Corner, Alexandre Arrechea, 2006

Installation with video, 55 x 55 inches each

Possible Destinations, Luis Gárciga, 2009

Video, 10 minutes

Hairball (Pendejo), Tony Labat, 2013

Digital wallpaper print, 8 x 8 feet

Kevin Hong is a junior at Harvard University, where he concentrates in History of Art and Architecture. He reads fiction for the Harvard Review and is blog editor of the Harvard Advocate. Kevin was born in Chicago, Illinois, and currently resides in Needham, Massachusetts.