Book Review: The Ecstasy and Agony of WBCN

By Adam Ellsworth

I found myself most interested by the fact that so many of the changes that took place at WBCN made absolute sense to me, even if I had an aesthetic beef with them.

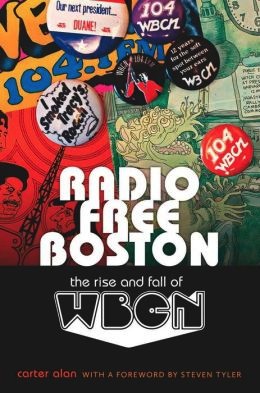

Radio Free Boston: The Rise and Fall of WBCN by Carter Alan (forward by Steven Tyler) Northeastern University Press, 352 pp., $25.95.

It probably goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: they don’t make radio stations like WBCN anymore.

At least it goes without saying if you’re older than 40.

For the rest of us, the idea that WBCN was special once upon a time might be actual news.

In the late ’90s and into the new century, when we youngsters were listening, “The Rock of Boston” was just another station that played Limp Bizkit. The nicest thing you could say about ‘BCN at that point was that it was almost, but not quite, as obnoxiously vulgar as WAAF.

It’s meathead musical decisions like giving airtime to the titans of nu-metal that Carter Alan had in mind when he included “and Fall” in the subtitle of his new book, Radio Free Boston: The Rise and Fall of WBCN. This shouldn’t detract, however, from the fact that the “Rise” part was pretty spectacular. Alan was himself a DJ at WBCN for nearly 20 years (he’s currently at WZLX), but to his credit, he hasn’t written a memoir, or an over the top love letter. Instead he’s written a book that is incredibly well researched, deeply interviewed, and as close to being “down the middle” as is possible for a writer who was involved in much of the action. My only real quibble with Radio Free Boston is that Alan points to the station breaking Aerosmith as a good thing. I think we’d all be better off if that never happened.

Putting questions of musical taste aside, what Alan has done with Radio Free Boston, whether he intended to or not, is give the entire history of commercial radio, from the days when nobody listened to FM, to the present, when most people don’t even know that AM exists. He does this without ever writing about anything that isn’t directly related to WBCN. Such a narrow focus on the micro, I know from my journalism school days, is “wrong,” and yet it works perfectly here. Perhaps it’s just that the saga of ‘BCN touches on so much of radio, American, and musical history that the macro is implied.

Now then, a few facts. WBCN (standing for “Boston Concert Network) was not always a rock station. It began life in 1958 playing classical music. Mitch Hastings started the station, and while he isn’t much more than a significant footnote to our rock and roll story, he’s a hugely important figure in the development of FM radio. It was he who was a pioneer in realizing that while hardly anyone broadcast on the FM band, it offered a far cleaner sound than AM. Being a practical sort, Hastings knew that the only way for FM radio to take off was to invent an FM radio specifically for cars (hard to believe now, but these radios didn’t always come standard). So, along with an engineer from Raytheon, he went off and created just such a device. He also had a hand in inventing an FM transistor radio. Market for his vision created, only then did he get into station ownership, beaming static-free classical music out from the Hub of the Universe.

Despite that crisp FM sound, WBCN was no cash cow. Enter Ray Riepen, “the hippie entrepreneur,” as he’s described in Radio Free Boston. Riepen hailed from Kansas City but moved to the area to attend Harvard Law School in the mid-’60s. While he was a fairly clean-cut grad student, he was also intrigued by the countercultural revolution that was blossoming around him. Riepen’s interests in this new youth culture were genuine, but he also knew an opportunity when he saw one, so in 1967 he opened what would become Boston’s premiere rock club, the Boston Tea Party. Riepen soon passed on the chore of managing the venue, first to Steve Nelson (these days, president of the Music Museum of New England), and then to Don Law (these days, master of the Boston concert universe). Freed of worrying about the Tea Party day-to-day, Riepen turned his sights to radio, after reading that an FM station in San Francisco was having moderate success playing rock music. If it could happen in San Francisco, he figured, it could happen in Boston. After all, as he’s quoted in Radio Free Boston, “There were 84,000 students here and they were all starting to smoke dope. They were obviously hipper than the assholes running broadcasting in America.”

Indeed. Riepen began looking for an FM station that was already in operation but could use some new listeners (i.e., one that had nothing to lose), which led him to WBCN. The rest, as they say, is history. At 10 p.m. on March 15, 1968, the classical music stopped, and “Mississippi Harold Wilson” (real name Joe Rogers) dropped the needle on “Nasal Retentive Calliope Music” by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, leaving it on just long enough to make clear to everyone listening that for the next seven hours, something very different would be happening over at WBCN. Next up was Cream’s “I Feel Free,” and a whole night full of the latest in ’60s rock and roll. At 5 the next morning, right on schedule, the classical music returned, but by May of ’68, Riepen and his salespeople had done such a good job securing advertising dollars for the overnight hours that Mitch Hastings and the station’s board of directors turned the controls over to the rock and rollers full-time. “The American Revolution,” as the station referred to itself, had begun. Roll over Beethoven.

All of this, not to mention the whole first half-decade or so of ‘BCN’s existence, is of course entertaining stuff and exactly as revolutionary as the station itself claimed, but it’s also already well established (and the subject of an upcoming documentary by former station intern turned on-air talent Bill Lichtenstein). It’s everything that comes next in the story that makes Radio Free Boston such a fascinating read, as we see the station change (often begrudgingly) with the times. Some of these changes are good (the introduction of punk to the playlists), some of them not so good (both the morning AND afternoon shifts taken up by “shock jock”-style talk shows in the first years of the twenty-first century). Along the way, there are heroes (Charles Laquidara), villains (Opie and Anthony), and genuinely decent music fans who are often forced to make decisions they don’t like for purely business reasons (Oedipus).

I found myself most interested by the fact that so many of the changes that took place at WBCN made absolute sense to me, even if I had an aesthetic beef with them. For example, in the earliest years of the station, the DJs could literally play whatever they wanted, and they often did. The results could be thrilling, and a much needed respite from the predictability of Top 40 radio. Or, as Alan is more than willing to acknowledge, they could be completely self-indulgent. That’s why when WCOZ came along in the ’70s there were stretches when they wiped the floor with ‘BCN in the ratings. It’s not that ‘COZ had more musical knowledge or better taste. Actually, they had less musical knowledge and worse taste! But they knew what most people wanted to hear, and it wasn’t a long forgotten B-side by a band that was too out there to be really enjoyed by the masses anyway. This may be troubling to a music geek like me, and it’s easy to blame “the suits” for reining in the DJs, but that was and still is the reality of the market.

At times, WBCN did go too far to chase ratings (playing the aforementioned Limp Bizkit and co., for example), but it’s still true that the freedom to play whatever the hell you want must be used wisely, or you’ll be the only one actually listening. Ultimately, ‘COZ went off the air decades before ‘BCN did, but not before the former caused the latter to make some very real changes to their approach. This story would repeat itself over the years with WZLX and WAAF (and to a lesser extent WFNX, my all-time favorite Boston radio station, if only by default) playing the role of scrappy upstart out to steal ‘BCN’s listeners.

When the end finally came, in August 2009, WBCN wasn’t really WBCN anymore anyway. It was the end of an era, but it was more than time to turn out the lights. In a confusing transaction that Alan doesn’t even attempt to explain the minutiae of (I don’t blame him), WBCN, “The Rock of Boston,” turned into WBZ-FM, “The Sports Hub” (that ‘BCN was on 104.1 FM and WBZ on 98.5 FM isn’t worth exploring here). Ironically, the “Sports Hub” has been the biggest success story in Boston radio of the past few years, first nipping at the heels of the long entrenched local sports radio powerhouse WEEI, and then finally overtaking them in the ratings. As a result, WEEI has had shake-up after shake-up to stay competitive. As a loyal “Sports Hub” listener, I love it. But after reading Radio Free Boston, there’s a tiny part of me that feels bad for WEEI. They were trendsetters after all. They invented the sports radio market in Boston, paving the way for 98.5 to march in and trounce them. Then again, that’s radio. Change with the times, or get out of the way.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has a MS in Journalism from Boston University and a BA in Literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.

nice piece. but as someone who well remembers wbcn, i recall there was a political dimension to the station, represented by commentators like danny schecter, “news dissector.” that was part of the station’s identity & appeal. any mention of it in the book?

Harvey, fantastic point. The book does talk about this. As a matter of fact, the news/politics side got smaller as the years went on, just as the music got more and more “mainstream.”

Thanks, Adam, for calling Charles Laquidara a “hero,” because he was my “hero” too, for putting me on the air for his delightfully loony show. Circa 1979, I was a film critic for the The Real Paper, Charles invented this few-minute section for his morning program called “Dueling Critics,” utilizing the “Dueling Banjo” music from Deliverance. I’d do my part from my home, in my PJs, calling in on the phone. It was tongue-in-cheek Ebert-Siskel. One of us would lead with a several-minute review of a current movie. The other would follow with an attack on the review and on the credibility and credentials of the so-called reviewer: “I can’t believe what a pompous, stupid commentary,etc.” When the reviewing was over, and Charles had put on a song, he’d call me back and we’d laugh at our insults. It was, as they say, all in jest, and, hopefully, fun for the audience to hear pretentious film criticism punctured by both of us.

Sounds like it was fun Gerald!