Theater Review: Learning the Language of “Tribes”

Dramatist Nina Raine probes the complex nature of tribal affinities, delicately examining how precariously communication depends on whether people listen to one another carefully, or not.

Tribes by Nina Raine. Directed by M. Bevin O’Gara. Staged by the SpeakEasy Stage Company at the Stanford Calderwood Pavilion, Boston Center for the Arts, Boston, MA, through October 19.

By Iris Fanger

The American Heritage Dictionary defines “tribe” as “a group having a common distinguishing characteristic.” Playwright Nina Raine’s perceptive and poignant drama “Tribes” explores the concept of tribe, starting with its resonance in the make-up of a family — dysfunctional as it is — then widening her quest to encompass a larger tribe, the world of the hearing impaired. The common thread, uniting the specific and the universal, is the complexity of human communication, the gulf between those who can take part and those who can’t. We ache for Billy, the hearing-impaired youngest sibling, who is so often left out of the conversations.

Dramatist Nina Raine probes the complex nature of tribal affinities, delicately examining how precariously communication depends on whether people listen to one another carefully, or not. The domestic ties that bind or chafe — woven deeply into the common rituals of family life — only add to the layers of confusion and yearning. Tribes won Olivier and Evening Standard nominations for best play at its’ London premiere and the Drama Critics Award for Best Foreign Play and the 2012 Drama Desk Award.

For the SpeakEasy Stage production, director M. Bevin O’Gara has followed in the steps of the New York presentation, staging the play in the round. The audience feels the same confusion as Billy because some of the dialogue is lost when actors turn their backs, even though many of their lines are projected on screens placed at four corners of the stage. The lighting is often dim, further reducing the ability to make out the actors’ facial expressions. However, the emotions and animosities come through — no problem — as each of the characters, fueled by his or her own ego, tries to best the other via anarchistic king-of-the-mountain combat.

Billy was taught to lip read rather than depend on sign language because his father, Christopher, a pompous scholar and author, was determined to keep him out of the deaf community. Beth, Billy’s mother, serves as the stalwart peacemaker for the entire family, trying to make nice no matter the afflictions that beset her other children. There’s Daniel, who retreats into his head where he hears voices, and Ruth, a failed opera singer. Now returned from university, Billy completes this tiny tribe which lives together at home.

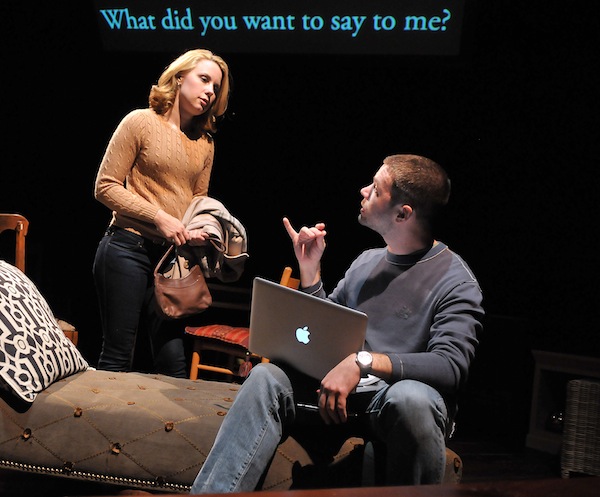

Erica Spyres and James Caverly in TRIBES at the SpeakEasy Stage Company. Photo: Craig Bailey/Perspective.

The fireworks begin when Billy meets Sylvia at a party and falls for her. Sylvia, who can hear but grew up with a deaf father and mother, is now losing her own hearing because of a genetic condition. She’s caught in a painful trap: she learned to sign in order to communicate with her parents, but she is frantic to escape her fate. When she and Billy move into an apartment together, she teaches him sign language, giving him entry into the deaf community, where he feels more at home than ever before. Raine adds a number of plot complications that, in the second act, sometimes grow beyond comprehension, but the performances by the excellent company of six actors are so lucid that it hardly matters.

At the center, alone, stands the hearing impaired actor, James Caverly, a two-year veteran of the National Theater of the Deaf, who plays Billy. His performance is a luminous mix of courage, exploration, humor and good sense, making him a linchpin for the ensemble. The fact that he shares the condition of deafness with the character he portrays only adds to our empathy. Patrick Shea who has been missing from our stages for too long, is cast as the self-serving Christopher, an entitled patriarch who does not understand why his judgment is being questioned. Nael Nacer as the tormented Daniel transforms before our eyes, tested by having to deal with losing everything he values and everyone he loves. Adrianne Krstansky undercuts Beth’s sweetness with a wry irony, while Kathryn Miles turns Ruth into a perpetually exploding bomb. Erica Spyres as Sylvia makes us share her dilemma, which is expressed both through language and the evocative gestures of signing. I dare say you will not soon forget the final moments of Act I when Spryes turns the consequences of her loss into a coup de theatre of searing emotional intensity.

Raine’s play also delves into the age-old complications between fathers and sons and their expectations of each other, and the relationship between brothers who dearly need each other for emotional support. Faced with losing Billy as his comrade, Daniel retreats into darkness, only to be redeemed at the end of this compelling play in a reconciliation of Biblical power that is enhanced by signing.

Iris Fanger is a theater and dance critic based in Boston. She has written reviews and feature articles for the Boston Herald, Boston Phoenix, Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, and Patriot Ledger as well as for Dance Magazine and Dancing Times (London).

Former director of the Harvard Summer Dance Center, 1977-1995, she has taught at Lesley Graduate School and Tufts University, as well as Harvard and M.I.T. She received the 2005 Dance Champion Award from the Boston Dance Alliance and in 2008, the Outstanding Career Achievement Award from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts. She lectures widely on dance and theater history.