Visual Arts Review: “Historias: Latin American Works on Paper” — An Invitation to Expand Your Horizons

Many artistically inclined people would probably cite Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera as the region’s representative artists. That is a shame, because the breadth of contemporary Latin American visual art, as shown in this splendid exhibition, is vast.

Historias: Latin American Works on Paper. At Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, R.I. Through January 5, 2014.

by Adara Meyers

“Choose your words wisely.” That adage assumes an increasingly prickly relevance as citizens around the world deal with political movements that create (or try to keep up with) boundaries in a world that is dominated by evolving jargon and socially driven technology. One need only look back at the last few years in U.S. history (not to speak of centuries of violent upheaval) to understand just how fundamentally present borders are in our lives — in the physical, ideological, and ephemeral categories that stoke hotly debated issues such as immigration reform, inform notions of personal safety and self-governance, and influence media conglomerates’ marketing analytics.

It could be argued that culturally laden categorization — who is near and who is far, what is uniform and what is “other” — has become more central than ever in contemporary art and creative praxes. The dazzling aesthetic range exhibited by the fifty-six pieces in Historias: Latin American Works on Paper at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum dramatizes the engrossing and conflicting territories of development, destruction, and shared humanity.

From the hallway, the exhibit, neatly tucked into a two-room gallery, looks staid. But any notion of decorum vanishes quickly. At a glance, you experience, head-on, a torrent of Latin American dreams and political perspectives expressed through vibrant, albeit painful, images. There’s Colombian printmaker Guillermo Silva Santamaria’s Crucifix and Execution by Firing Squad, etchings with starkly violent figures highlighted in eerily hued aquatint. Mexican photographer Marcela Taboada’s Solitude is an arresting portrait of a young person’s face and torso ambiguously compressed by the hands of an unseen elder.

The exhibition is at times both grisly and beautiful, public and private, reflecting curator Alison Chang’s vision, which reflects a belief that the personal can serve as a lens to extend cultural understanding far beyond its geographic and temporal limitations. The wall text introducing the show makes the point directly: “The word historias — with its dual meaning of both ‘histories’ and ‘stories’ — evokes the rich cultural histories of Latin America’s diverse populations and the role that storytelling and oral history plays in the transmission of the past.”

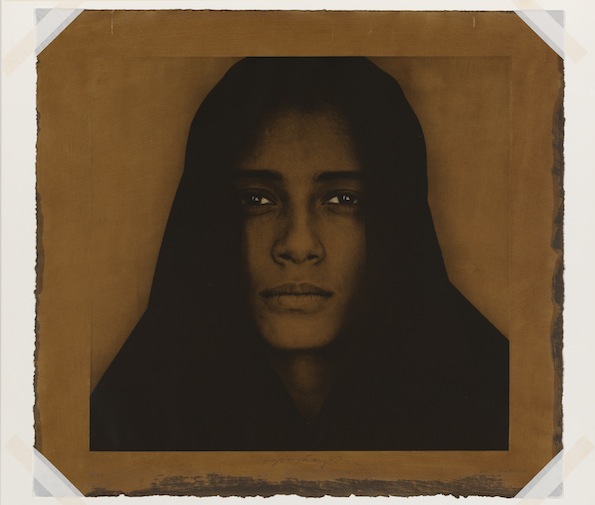

Luis González Palma, “The Silence” (“El Silencio”), 1998. Nancy Sayles Day Collection of Modern Latin American Art. © Luis González Palma.

As the exhibition’s title suggests, all of the works were created in two-dimensional media, but those that immediately drew me in were ones with movement and performance at their cores, such as Peruvian photographer Javier Silva Meinel’s Waca Wacas y Perro, Paucartambo, Cuzco, Peru. Shot in 1996, the print deftly captures both the disquieting aftermath of colonialism in Andean history as well as modern representational conflict in daily life. The positioning and costuming of the three dancers, foregrounded by an errant dog, left me wondering about what kind of prior interaction (if any) they had with such characteristically Western spaces as a commercial photography studio or proscenium theatre. Where does authenticity start and stop — and how is it defined — in the context of a performance tradition born from the ashes of religious coercion?

I moved on to examine an entrancing four-piece photogravure series of untitled works by another Peruvian photographer, Milagros de la Torre. I was transfixed by its stillness and power, which was rooted in an atmosphere of bygone daily activity. Articles of clothing loom in austere darkness; I imagined a number of scenarios: it was the scene of a crime, an estate sale, a forbidden closet, a box of long-forgotten photographs. De la Torre, the child of a major police chief during the era in which Richard Nixon first declared America’s War on Drugs, grew up with an acute threat of insecurity and fear.

Given the growing awareness of gender parity in the visual art market as well as the culture at large, I was disappointed that of the twenty-seven artists represented in the exhibition, only six are female. I yearned for more works by women exploring female perspectives on the challenges of political activism and economic disparity; artists working in this vein include Mexican photographers Daniela Rossell (whose 2001 series, Ricas y Famosas, was on view at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art last year) and Lola Álvarez Bravo, a pioneering figure who turned her creative lens on daily street life and strife. An exhibition dedicated to the multifaceted nuances of Latin American representation through personal testimony and historical narrative is well poised, for example, to illuminate how life-or-death tensions in earlier centuries of war and poverty are influencing women’s struggles with issues such as domestic violence and drug trafficking.

Don’t get me wrong: women’s art should not be confined to meditations on victimhood. In fact, a huge strength of the exhibition is the number of its works that combine social commentary in pointedly personal narratives. Women exploring the latter, such as the aforementioned de la Torre series and Argentinian printmaker Liliana Porter’s four-print series of tiny toys and objects, provide some of the highlights of the exhibition. Imbued with a stunningly palpable sense of lightness — both tonally and aesthetically — Porter’s objects also evoke conflicting senses of familiarity and unease. In her artist statement on her Web site, Porter talks about how these “theatrical vignettes” reflect our enduring search for significance in life and memory: “The objects have a double existence. On the one hand, they are mere appearance, insubstantial ornaments, but, at the same time, have a gaze that can be animated by the viewer, who, through it, can project the inclination to endow things with an interiority and identity.”

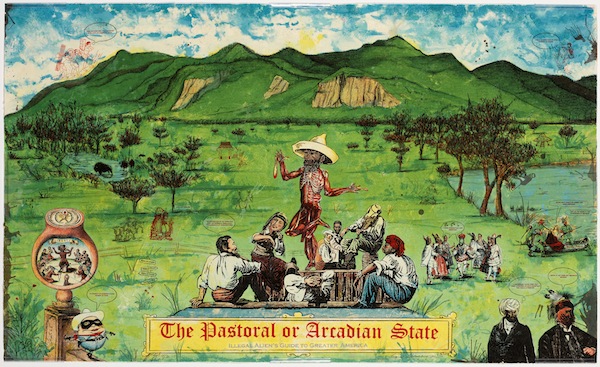

Enrique Chagoya, “The Pastoral or Arcadian State, Illegal Alien’s Guide to Greater America,” 2006. Gift of Faye Hirsch. © Enrique Chagoya.

The push and pull of public and private life is also at the center of Cuban photographer Abelardo Morell’s Camera Obscura Image of Havana Looking Southeast in Room with Ladder. At first look, I believed a mural was gracing the walls. I couldn’t quite tell if it was depicting buildings. The wall text clarified the image: Morell “transformed an entire room into a camera obscura” and “the cityscape of Havana is superimposed, upside down, onto objects of personal and cultural significance.” This idea of a staged scenario is reflected throughout the exhibition, which explores how we perceive, curate, and construct the constant and ephemeral spaces we occupy.

Right in the middle of the exhibition’s second room stands Chilean painter Roberto Matta’s Abstraction, an enormous Surrealist vision depicting menacing airplanes floating about what could be either a natural or a constructed landscape. The woman lying on her back seems to be a natural fit, yet she strikes me to be as out of place as the mountains that sit directly behind her.

The haunting paradox that Matta addresses concerning the intimacy and distance among people, systems, and ideologies are emblematic of Historias: Latin American Works on Paper. Recently, interest in Latin American art has been gaining steam in galleries and museums across the United States. Still, it’s probably not much of a stretch to say that many artistically inclined people would probably cite Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera (whose lithographic self-portrait is, admittedly, included in the exhibition) as the region’s representative artists. That is a shame, because the breadth of contemporary Latin American visual art is vast, from Venezuelan printmaker Jésus Rafael Soto’s Jai-Alai, an homage to the title indoor ball game and its Spanish-Latin American history, to Enrique Chagoya’s scathing satire The Pastoral or Arcadian State, Illegal Alien’s Guide to Greater America. This exhibition is an invitation to expand your horizons, and not only New Englanders have the opportunity: the entire exhibition is also on view through the RISD Museum’s Web site.

Adara Meyers is a playwright, editor, and Managing Director of Sleeping Weazel, a theatre company producing live performances and online cyber art gallery exhibitions. She is the 2014 Fellowship Merit Award recipient in Playwriting/Screenwriting from the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. BA, Wheaton College.