Book Review: Herbert Huncke — The “American Hipster” Who Influenced The Beat Movement

Hilary Holladay’s biography of Herbert Huncke provides valuable insight into a person and world that were begging to be explored.

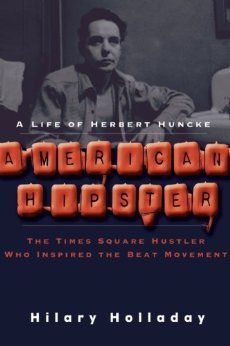

American Hipster: A Life of Herbert Huncke, The Times Square Hustler Who Inspired the Beat Movement by Hilary Holladay. Magnus Books, 400 pp., $17.95.

By Troy Pozirekides

Somewhere on the lower rungs of the Beat Generation, beneath the vaunted triumvirate of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs, stands Herbert Huncke, the subject of Hilary Holladay’s biography American Hipster. Holladay, a Beat scholar and founding director of the Kerouac Center for American Studies at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell, MA, claims that “to know Huncke’s story from beginning to end is to know the Beat Movement inside and out.” In the process of arguing this claim, she makes a case for recognizing Huncke as a writer on his own merit, not merely a compelling character who inspired his more prominent peers. Over 400 well-researched pages, she provides a captivating look into a man who, by embodying the seedy underbelly of New York, evoked “beatness” to a tee.

Herbert Huncke was born in 1915, making him older than the chief Beat writers. Raised in Chicago, he exhibited from an early age an impressive wanderlust and a rampant homoerotic curiosity (in the prologue we learn that a twelve-year-old Herbert ran away from home, returning after he “had oral sex with a stranger”). He escaped his unsupportive parents and made his way to New York in 1939 with the vague desire to “be an actor…to write and travel all over the world.” He brought with him a heroin problem and a penchant for petty thievery that he would steadily maintain his entire life. Soon he was prostituting himself in Times Square to support his addiction, but also as an end in itself.

Aside from a memorable experience with a carnival hermaphrodite (later immortalized in his story “Elsie John,”) and a series of interviews with the sex researcher Alfred Kinsey, Huncke’s pre-Beat life is uneventful, especially from a bookish perspective. A stint in the Merchant Marine permitted him the travel he had dreamed of, but he showed little in the way of ambition in comparison with, say, Kerouac, who at a similar age demonstrated a tremendous literary appetite and output (collected in Atop an Underwood). Huncke’s stories about this period of his life would come later, eventually earning him Kerouac’s praise as a “perfect writer.”

Holladay’s narrative of Huncke’s life picks up considerably when he, and we, are introduced to the major figures of what would later be called the Beat Generation. William Burroughs comes first—Huncke watches as the buttoned-up Bill, heir to the Burroughs Corporation fortune, gets his initial fix of the opiate that inspired his first major novel, Junky, in which Huncke appears as the thinly veiled character “Herman.”

From here on, Holladay begins to dramatize the divide between Huncke and the other Beat writers. Beyond the economic disparity between Burroughs and Huncke, she contrasts the treatment of characters in their fiction as well. Huncke’s depiction of Vickie Russell, in his early story “Detroit Redhead,” is caring, while Burroughs focuses on the woman’s predatory nature:

Where Huncke glimpsed beauty and frailty, Burroughs mined violence and rage…Burroughs’ way of presenting criminals in Junky confirms our worst fears and elicits an occasional shocked guffaw. Huncke’s, in contrast, provokes a much more subtle and empathetic reaction.

This is one of many instances where Holladay explores Huncke’s ability “to humanize the troubled wayfarers that most other writers would consign to parody or peripheral roles.” And while she usually shies away from naming these “other” writers, it is clear that she has Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs in mind. We see later how, in spite of his storytelling ability, the major Beats saw Huncke as “a novelty, a tattered mascot, he would never be their social or intellectual equal.” Indeed, when Huncke appears in the major works of his more successful friends, his writing is never mentioned.

Part of this ambivalence stems from Huncke’s mercurial involvement in his friends’ lives; he was more at home with his fellow 42nd Street lowlifes than with the budding Beats. In Huncke’s view, “they were all so very, very, intellectual—I felt as though at best they were patronizing me…Still, I found myself becoming involved with them to such an extent it became impossible for me to imagine pulling away.”

Huncke stuck around long enough to exert a fair degree of influence. Kerouac cites him as the coiner of the term “Beat,” a word Huncke often used to describe himself, battered by heroin and hustling. Later Kerouac would imbue the word with his characteristic interest in religiosity, his preference for Catholic beatitudes and visions of transcendence. His admiration of Huncke also likely led to his adoption of the long dash as a syntactical unit in his writing, though the two utilized the ligature in disparate ways. Huncke’s dash, which nearly always replaces serial commas, evokes the shallow, halting breathing of the dope addict narrator. Kerouac used the dash to break up Proustian chunks of poetic language. The effect is musical, akin to a rest, or as he described it, “vigorous space dash separating rhetorical breathing (as jazz musician drawing breath between outblown phrases).”

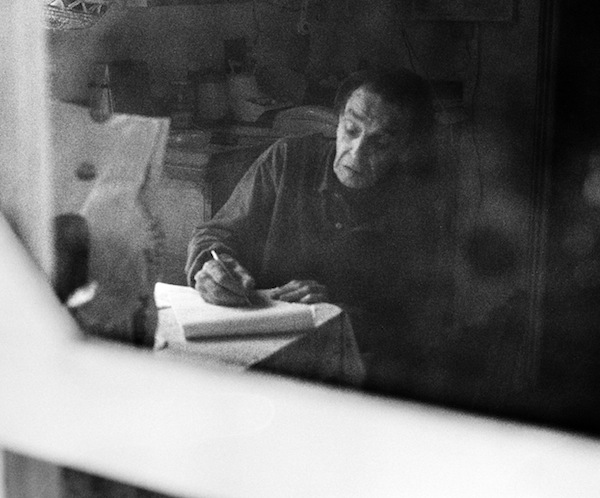

But these are perhaps Huncke’s most significant contributions. Write though he occasionally did, “crouched in a Times Square pay toilet with a notebook on his knees” (as described in The Herbert Huncke Reader), his preoccupation with the cycle of copping and fixing became a full-time occupation in itself. Huncke lay dormant during the movement’s vital developmental years, “spending most of the 1950s in prison” thanks to his “repeated offenses and drug habit.” When he was released, his friends were on the cusp of fame:

In his absence, a literary movement sprang to life…[Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs] were working very hard, creating themselves and their literary legacies…Huncke, meanwhile, was spending his days—his years!—with nothing to look forward to besides a cigarette or a conversation with a fellow con. He always said he found it difficult to write in prison, so his incarceration was not productive in that way.

Once “Howl,” On the Road, and Naked Lunch received critical acclaim, Huncke could never quite get out from under the weight of the impressions his friends made of him in those works. For the remaining forty or so years of his life (he died — in spite of his sustained addictions — at the age of 81 in 1996), he gradually became classified as a fringe Beat figure, more of a cultural relic than writer. Thus, argues Holladay, Huncke’s literary reputation couldn’t escape a debilitating paradox:

His ties to the Beats, especially Ginsberg, had earned the book [his 1980 collection The Evening Sun Turned Crimson] its publication at last, yet those same ties damned him to a subordinate status.

Reading American Hipster will surprise the Beat aficionado who may not have realized how often Huncke was not around, thanks to extended jail stints and the agonies of addiction. In that sense, the book’s attempt to make a case for him as a neglected writer in the Beat canon falls short. Holladay, in describing Huncke’s addictions, characterizes him as “a recidivist with no sustained interest in going straight.” This is an apt summation of his literary pursuits as well, which show little of the creative drive of his better known peers.

Holladay’s biography does, however, provide valuable insight into a person and world that were begging to be explored. We learn about the tenuous homosexual relationships of a man who refused to call himself “gay,” and the unapologetic addiction that took over his entire life. Huncke’s lifelong problems with love, unrequited and otherwise, are of interest, as are his relationships with Joan Vollmer Burroughs and Peter Orlovsky. He demonstrated enormous empathy toward the troubled lovers of his best friends. Holladay also deftly captures Allen Ginsberg’s management of the “business of marketing the Beat Movement” in the decades following Kerouac’s death. In doing so, Ginsberg created the lucrative machinery that generated the money that sustained Huncke, heroin and all, up to his death.

Periodically, the book suffers from a detached, academic tone that, ironically, runs counter to the gritty realities of Huncke’s hustler existence. Too often, for example, are we given the blanket term “drugs” when a more specific identification of the substances involved would have better set the scene. The same could be said of the oddly distanced references to Huncke’s sexuality, which is curious for a book published by Magnus, which specializes in LGBT literature. Finally, when we are presented samples of Huncke’s writing, Holladay’s explications tend to overreach in their desire to promote his talent. The pumped-up exegesis does not give his “distilled version of oral storytelling” its modest breathing room.

Still, Holladay’s study deserves serious attention. She has painted a sweeping scene of a significant period of literary history. Her efforts to depict “the Times Square hustler who inspired the Beat Movement” underscore the difficulties of defining the movement’s parameters and members. “Beat” is a handy term to group together three singular American writers who had closely entwined private and professional lives. But, judging from their skills, ambitions, and work ethic, its very likely that these writers would have made an impact regardless of their ever having met. Calling themselves “Beat” — however fleetingly — was not crucial to their success. For Huncke, however, it was the cachet of the “Beat” movement and his place in it that sustained him, becoming, along with his addiction, an essential part of his identity. Defining himself as “Beat,” submitting (in part) to the movement’s hierarchy, assured him a modest degree of fame. With that in mind, we can perhaps more fully understand Ginsberg’s definitive description of his friend: “Huncke was beater than anybody.”

Troy Pozirekides is a writer, critic, and editor. Currently a senior at Boston University, he specializes in British and American literature of the twentieth century, from the poetry of Philip Larkin to the works of Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation. Troy is also a musician and jazz aficionado, playing trumpet and guitar. Follow him on Twitter at @tpozirekides.

Tagged: Allen Ginsberg, American Hipster: A Life of Herbert Huncke, Herbert Huncke, Hilary Holladay