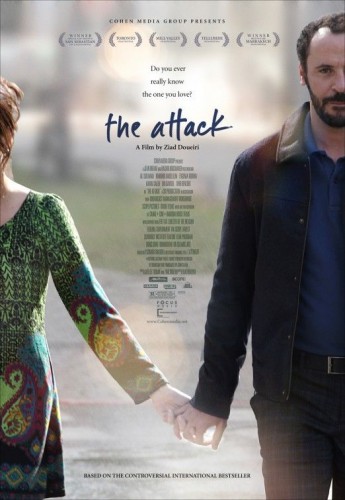

Short Fuse Film Review: “The Attack” — A Compelling Look at the Conflict Between Israelis and Palestinians

The Attack is a movie that tries to get to the core of violence without dissolving into its depiction.

The Attack. Directed by Ziad Doueiri. At cinemas around New England.

By Harvey Blume.

The friend with whom I saw Ziad Doueiri’s compelling film, The Attack, said when we left that it was remarkable how little violence was actually portrayed. That may sound like a strange comment to make about a movie that centers on a suicide bombing in Tel Aviv that kills 17 people, not counting the bomber, and leaves others maimed for life. Nor is that event entirely off-screen: some of its torn, bloodied victims are rushed directly to the hospital where Dr. Amin Jaafari, the film’s main character, practices medicine.

Still, the observation about the lack of violence is correct. I was tempted to remark in reply that The Attack lacked the sort of big budget muscle that would have enabled it to show Tel Aviv blown to—digital—bits. But that, I know, is pure cynicism, bred by watching too many Hollywood movies that have nothing going for them but immensely expensive variations on the theme of blow-up.

The Attack is a movie that tries to get to the core of violence without dissolving into its depiction.

Dr. Jaafari is an Israeli Arab. We see him accepting a prestigious award for his work in medicine during which he says to the audience that if he has learned one thing it is that there is a Jew inside every Arab, an Arab inside every Jew. The Israeli audience applauds this noble sentiment. The film commences to shake Jaafari from it.

While he is waiting to be introduced for the award, he gets a call from Siham, his wife. He can’t talk to her now, he says. We learn, through flashbacks, that the two have had the sort of romance we associate with French cinema—genteel, classy, with no lack of the Mediterranean as backdrop. What could be wrong with such an affinity?

The only thing wrong is that it turns out Dr. Jaafari didn’t know Siham, not what she did when not with him, not even why she married him. The Shin Bet finds proof it was she who blew herself up in that Tel Aviv party full of children. The hulking Shin Bet officer says, we trust Arabs like you and we are wrong; all you do is provide cover for killers.

Dr. Jaafari spends days in a solitary cell, music turned up so he can’t sleep. Finally, he is released. Yes, that was his adored wife’s body in the rubble. But how could she? Why would she?

He revisits their liaison for everything their passion might have obscured. All she wanted was a passport, she murmured once, over a shared, post-coital cigarette, a place to be from that didn’t involve so many check points. Jaafari traces her movements back to Nablus, on the West Bank. He finds her face on posters everywhere, applauding what she did against the Jews, the Jews who, as a renowned, local Imam intones, have no place in this land, no right to even a single grain of it.

Jaafari digs until he finds those who fitted her out with the bomb and learns from a video tape why she called him that last time: it was a goodbye kiss cum suicide note.

When Dr. Amin Jaafari returns to Tel Aviv, perhaps to his position at the hospital, neither we nor he know who he is. His Jewish colleagues no longer trust him. His Arab family suspects he has done nothing but lead the Shin Bet to them, to hound them no matter what. The peace treaty between Jew and Arab inside Jaafari is no more.

There’s much in this movie to remind you of current events: Dzhokar Tsarnaev, for example, and the smooth duplicity that left so many of his peers and associates with no inkling of the bombs he was about to plant. The Attack may, too, elicit thought of Egypt in its seemingly suicidal turmoil.

The Attack will, of course, bring you back to the immediate issue, its set and setting, the conflict between Israelis and the Palestinians, not that the movie proposes any solution. It ends with an isolated Dr. Jaafari struck dumb by the voices shouting inside him.

***

Director Ziad Doueiri (center) with actors Ali Suliman (right) and Reymond Amsalem (left) on the set of THE ATTACK. Photo: Ziad Doueiri.

Ziad Doueiri, the Lebanese-born director of The Attack, studied cinema in the United States and did camera work for Quentin Tarantino in several films. It was hard for me to detect an exclusively pro-Israeli slant to the film, or any lack of compassion for the plight of Palestinians, but apparently certain watchdog groups did.

In an interview with Anthem Magazine, Doueiri said that the Lebanese government at first approved the film—with “not a single scene or line of dialogue cut”—but when challenged by the Israel Boycott Committee, withdrew support. The Israel Boycott Committee is committed to the strategy of Boycott Divest Sanction vis a vis Israel. Eventually, The Attack was banned in much of the Arab world.

Doueiri’s response is as follows: “There are massacres and crimes and rapes going on now in the Arab world, and the Arab League can’t even agree on what to do about it. Yet, they unanimously agreed to boycott a film. Gamal Abdel Nasser couldn’t unite Arabs. I did. ”

Doueiri’s new film, Just Like a Woman, opened in July.

Harvey Blume is an author—Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo—who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in the New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.