Classical Music CD Review: Lutoslawski — The Complete Symphonies, Los Angeles Philharmonic/Esa-Pekka Salonen

It’s a pity Witold Lutoslawski’s music isn’t turning up on more orchestral programs in the U.S. this season and next— Benjamin Britten seems to be the centennial birthday boy of choice.

Lutoslawski: The Complete Symphonies. Los Angeles Philharmonic/Esa-Pekka Salonen (Sony Classical)

By Jonathan Blumhofer

It’s always nice when the anniversary of a composer’s birth or death—those arbitrary cornerstones of programming these days— actually results in something fresh and meaningful. Such coincidences are rarer than not, but this year the stars are aligning for the centenary of the great Polish composer Witold Lutoslawski, and one of the bright lights in the constellation comes courtesy of Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic (LAPO) who have finally completed their survey of Lutoslawski’s four symphonies for Sony Classical. They’ve been at it for a while: while this account of the Symphony no. 1 dates from 2012, the earliest recording (Symphony no. 3) was made in 1985, and the other two come from the early/mid-‘90s. Those three have been previously released on Sony, though the Symphony no. 2 has been in and out of print for the last near 20 years; it’s good to now have them all together in one place.

It’s a pity Lutoslawski’s music isn’t turning up on more orchestral programs in the U.S. this season and next—Benjamin Britten seems to be the centennial birthday boy of choice—but it is getting some serious air time in Europe and Asia, in part courtesy of Salonen and his current orchestra, London’s Philharmonia. They, along with composer Steven Stucky (who provided excellent liner notes for the current album), have created a website to commemorate the year-long celebration, filled with essays, videos, and even a composition game.

The lack of Lutoslawski in these parts is our loss, though, because, despite the fact that he was one of the most innovative figures of the postwar avant-garde, Lutoslawski’s is some of the most directly communicative, deeply expressive, and, dare I say, accessible music written in the last 75 years. To know Lutoslawski’s music is to experience the twentieth century as it unfolded in Eastern Europe—it shatters the notion that contemporary music can exist apart from real-world experience—and that alone makes it compelling.

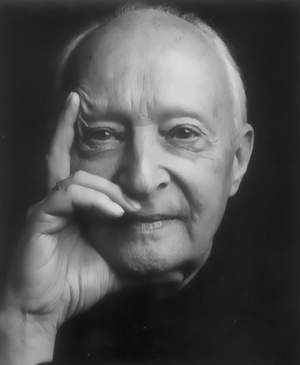

Born to a family with roots in the Polish nobility in 1913, Lutoslawski’s boyhood was upended by the First World War: the family fled to Russia where Lutoslawski’s politically-active father found himself on the wrong side of the Russian Revolution and was executed in 1918. Returning to Poland to find the family’s home in ruins, Lutoslawski’s early career was then interrupted by the outbreak of World War Two. He passed the years of the occupation in Warsaw, eking out a living by performing as half of a piano duo in cafes (the other half was another great Polish composer, Andrzej Panufnik), while also writing arrangements and beginning his Symphony no. 1 (which was only completed in 1947). Serendipitously leaving Warsaw shortly before the ill-fated Uprising of 1944, nearly all of Lutoslawski’s early music was destroyed, and the postwar years brought more oppression in the form of Soviet cultural diktats.

By the 1960s, Lutoslawski had emerged as one of the leaders of the Polish avant-garde, and his output over that decade and the next only cemented his position as one of the century’s most innovative and engaging musical minds.

Like his contemporary, György Ligeti, Lutoslawski spent a good part of the late 1940s and early 1950s writing music influenced by folk sources, culminating in his brilliant Concerto for Orchestra. With the cultural thaw that started in the mid-50s, though, Lutoslawski began presenting his more experimental scores, pieces like Musique funèbre (a memorial to Béla Bartók, which revealed Lutoslawski’s unique method of utilizing the full spectrum of chromatic pitches while not strictly adhering to the Serial method) and Jeux vènitiens (“Venetian Games,” which introduced chance, or aleatoric, techniques alongside synchronized musical events).

By the 1960s, Lutoslawski had emerged as one of the leaders of the Polish avant-garde, and his output over that decade and the next only cemented his position as one of the century’s most innovative and engaging musical minds. In addition to rethinking the harmonic and temporal aspects of his music, Lutoslawski frequently reworked musical forms. His String Quartet (1965) and Symphony no. 2 (1966-67) both employ a two-movement structure: the first movement is introductory, intended to whet the appetite for the second. The extraordinary Cello Concerto (1970) demonstrates a distinctive, narrative quality, latent with extramusical implications (which the composer strenuously denied).

His later works—Les espaces du sommeil, the Symphonies nos. 3 and 4, the Piano Concerto—reveal a composer still honing his style and reconciling disparate melodic and harmonic elements. The Symphony no. 4 in particular, premiered in 1993, the year before Lutoslawski died, is perhaps his most efficient essay in the genre, filled with sweeping, haunting, lyrical lines and passages of ferocious intensity and aggressive energy.

And this album features an appropriately thrilling performance of that piece and its three siblings to commemorate Lutoslawski’s hundredth birthday.

The Symphony no. 1 (1941-47) is a fascinating start for one of the twentieth century’s major symphonists. This is manic, teeming music—the wild first movement is the aural equivalent of careening too fast around mountain passes in a sports car—that grabs hold and refuses to let go. The slow second movement alternates brooding music for strings with an ironic central section that showcases the rest of the ensemble, while the concluding two movements trope the spirit of the first, sometimes quite darkly.

Stylistically, this is the most reserved work on the album, and it’s not difficult to understand why Lutoslawski grew unhappy with it: there are plenty of moments that feel as though the music is trying to break out of the formal restrictions of the genre. Still, it’s a brilliant piece that ought to be much better known than it is, and it’s played here with great panache. Salonen’s unfussy direction captures its whimsy and tragedy while ensuring that Lutoslawski’s brilliant orchestrations come across with great lucidity.

The Symphony no. 2 is in many ways the most Classical symphony of the four, its two movements organized according to essentially traditional means (the first movement, for example, is basically a rondo, alternating contrasting episodes followed by a recurring refrain) even as its musical content sounds like nothing that came before it.

This is perhaps the twentieth century’s greatest unknown (or least known) symphony, a grim, nihilistic essay that thwarts all efforts to achieve any sort of triumph. In its opening movement, Hésitant, scurrying, colorful figures pass in and out of view, interrupted by plangent double reed choruses. The second movement, Direct, alternates grand, lyrical statements with passages of anarchic rhythmic energy, building to bigger and bigger climaxes, only to collapse on itself and dissolve into two pitiful notes.

The recording on this disc dates November 1994, nine months after Lutoslawski’s death, and there’s a sense of Salonen and the LAPO paying tribute to the composer’s memory throughout their reading. The orchestra’s playing is strikingly intense, opening with crisp brass and wind riffs that are answered by the lamenting refrains. The finale, with its queasy opening statement for strings foreshadowing climaxes of heartbreaking anguish, is positively terrifying.

In contrast to the Second, the Third and Fourth Symphonies are relatively familiar and performed with some frequency. The Third (1972–83) won Lutoslawski the prestigious Grawemeyer Award in 1985, and this recording, made that year, is still the best out there, the playing electrifying and brilliant (I should also mention that Lutoslawski’s own account on Philips is no push-over, nor is Daniel Barenboim’s on Erato or Antoni Wit’s on Naxos).

The valedictory Symphony no. 4 (1993) is the most Romantic symphony Lutoslawski composed, opening with a soaring melody for clarinet accompanied by strings and harp before turning martial. The same forces recorded this work for an LA Phil Live release on Deutsche Grammophon in 2006 and, while the more recent document demonstrates 13 years’ familiarity with the music, there’s nothing wrong with this initial account: it’s freshness and technical assuredness is breathtaking.

The one non-symphonic track on the album is a new recording of Lutoslawski’s short Fanfare for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, composed in 1993. If you think humor and contemporary music don’t (or can’t) coexist, this is 55 seconds of charming Modernism to prove you wrong.

In the early-1970s, Lutoslawski wrote that

I have a strong desire to communicate something to people, through my music. I am not working to win myself many “fans;” I do not want to convince, I want to find. I would like to find people who in the depths of their souls feel the same way as I do. They are the people who are closest to me, even if I do not know them personally. I regard creative activity as a kind of soul-fishing, and the “catch” is the best medicine for loneliness, that most human of sufferings.

That’s a noble sentiment, as valid now as it was 40 years ago, and this superb addition to the Lutoslawski discography helps ensure that his music will continue finding souls for the foreseeable future.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Esa-Pekka Salonen, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Lutoslawski: The Complete Symphonies