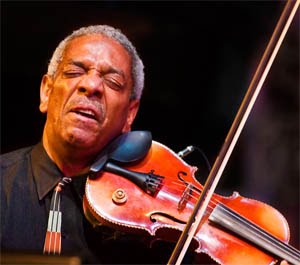

Jazz CD Review: Violinist Billy Bang’s Superb Final Recording — “Da Bang!”

When I saw him, he was rarely still on stage: a Billy Bang performance was something like a dance.

Da Bang!, Billy Bang, violin, Dick Griffin, trombone, Andrew Bemkey, piano, Hilliard Greene double bass, Newman Taylor-Baker, drums. TUM Records.

By Michael Ullman

Born William Walker, violinist Billy Bang, who was nicknamed after a now obscure cartoon character, died of cancer soon after this disc was recorded in 2011. He had a rocky life. Born in Alabama in 1947, he was raised in the Bronx and sent to school in Harlem where as a small child he was given a violin: he said he would have preferred a saxophone. Eventually he was sent as a scholarship student to an elite prep school in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. (Arlo Guthrie was a classmate.) The upper class educational experience confused him, and he dropped out.

Bang was drafted into the army and soon found himself in Vietnam where, still a teenager, he took unwilling part in combat. He came back, it would seem, permanently shaken. Bang said he tried to find peace through drugs, drink, and revolutionary activity: “My inability to bravely confront my personal demons, my experiences in Vietnam, has been a continuous struggle . . . At night, I would experience severe nightmares of death destruction, and during the day, I lived a kind of undefined ambiguous daydream.” Eventually, he returned to the violin: he made the reunion sound like it was only a matter of chance. He saw three violins in a pawnshop and bought one.

He developed a wild technique, or perhaps manner. When I saw him, he was rarely still on stage: a Billy Bang performance was something like a dance. He started recording in the mid 70s with a cadre of avant-garde players. (Over his career he recorded almost 30 albums as a leader, another dozen or so with various co-operative groups and many more as a sideman.) Performing with the Sun Ra Arkestra probably taught him the value of combining music and theatricality—many of his early performances, free or structured, included interludes of poetry and other kinds of recitations. Through music, he found a sense of mental balance: with one of his most successful groups, the String Trio of New York, Bang played a tune called “Catharsis in Real Time.” Still, there was a breakthrough about his Vietnam experience to come: in 2001 he made the raw Vietnam: The Aftermath, a recording that featured other musicians who also served in the war. The compositions included “Tet Offensive.” The late Butch Morris conducted, and he spoke to me movingly of the tears and courage of those sessions.

Da Bang!, the violinist’s last recording, doesn’t proffer that level of intensity or distress. With tunes such as Don Cherry’s “Guinea,” Ornette Coleman’s “Law Years,” Miles Davis’s “All Blues,” and Sonny Rollins’s joyous “St. Thomas,” the album comes off as a glowing tribute to Bang’s musical influences and heroes. The horn on the date is trombonist Dick Griffin, who early in his career played and recorded with Rahsaan Roland Kirk. (On LPs such as The Eighth Wonder of the World, Griffin demonstrated his ability to play several notes at the same time. Through the use of multiphonics he could simultaneously play all three parts of Ellington’s “Mood Indigo,” convincingly.) Griffin provides a grumbling, amusingly vocal solo on the opening number, Barry Altschul’s “Da Bang,” which is built over Hilliard Greene’s appealing bass line.

Bang’s virtuoso solo comes in his unaccompanied introduction to Don Cherry’s “Guinea,” a piece that, on the recording Old and New Dreams, opened with a kind of trumpet fanfare. Bang brings a tremulous flurry of energy to Cherry’s folksy melody. Then he worries some double stops, aggressively attacking with his bow. Eventually he introduces pizzicato effects that dominate the rest of his opening statement. What is remarkable is the engaging musicality, even the genial lyricism, of this agitated introduction to a piece that retains a kind of innocence even after the band enters over Newman Taylor-Baker’s solid drumming.

Bang’s composition on the album is “Daydream,” which is introduced gently by pianist Andrew Bemkey. It’s as sweet as a composition by Satie. Still, Bang’s statement of the lovely theme exudes his distinctive urgency: a startling force that comes from the pressure of his bow and from his decisive attacks on the strings. Bang played in formidable avant-garde groups, but there is nothing forbidding about his music or his exciting approach to improvisation. His was not what you would call a classical technique: but it was uniquely his, though, and it will be missed.