Poetry Review: A Spanish Metaphysical Poet Searching for Songs of Truth

Poet José Ángel Valente deeply considered what kind of lyricism remains legitimate; that is, truthful, not deceptive; a song that moves us to truth, not a Siren’s song.

Landscape with Yellow Birds: Selected Poems by José Ángel Valente. Translated from the Spanish by Thomas Christensen, Archipelago Books, 335 pp., $18.

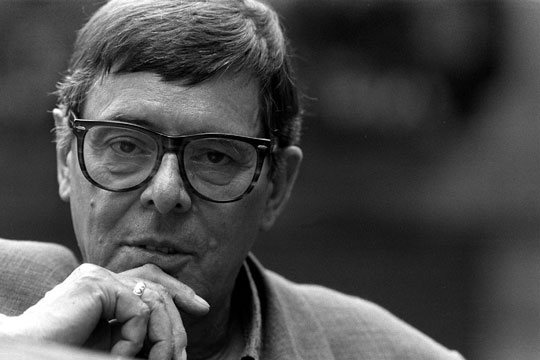

By John Taylor

Thomas Christensen, the translator of this excellent book, rightly observes in his preface that the poetic language of José Ángel Valente (1929–2000) “is sharp, clear, and intensely present.” This is indeed the impression given by Landscape with Yellow Birds, a bilingual selection gathering verse from the Spanish poet’s first book, In a Hopeful Mode (1953–1954) through his last, Fragments from a Future Book (1991–2000). So pellucid and void of lyrical murkiness is Valente’s style that a transparent surface is formed time and again, as it were, well beneath which various psychological and metaphysical depths can be glimpsed and pondered. When it comes to love, the insights take one’s breath away:

The bodies remained on the lonely side of love

as if negating each other without negating desire

and in this negotiation a knot stronger than themselves

indefinitely bound them together.

The lines sum up an amorous relationship that is not always easy to define (and even less so to be in), and they strike one as “true,” a word that has become questionable nowadays yet that gathers force and imposes itself as one reads this generous selection. In an early poem, Valente raises a plea “that the word be nothing but truth.” The Spanish term for “word” here, palabra, applies to the entire discourse as well. By writing poetry, Valente is struggling toward a truth—not necessarily known at the beginning of the poem—that he might be able to reach and thereby formulate. To his mind, seemingly, there is no other valid reason for writing poetry. At the same time, as he specifies in “Second Homage to Isidore Ducasse,” “poetry must have practical truth”—as do the lines quoted above. Their “truth” can be applied to situations we all experience. Valente speaks straight from the heart in ways that eschew all irony and posturing.

This is by no means to suggest that he is poetically or philosophically naïve. In fact, in a later piece, a prose fragment, he revisits this notion of practical truth and admits to his skepticism:

Sometimes I feel so close to death. I wonder to whom such an observation can be useful. In the end we do not write about what is useful, I think. So why not articulate a trivial truism? The proximity of death is the meeting of two flat, empty surfaces that melt away from mutual repulsion. Is that all? I don’t know. To pass to the other side is insufficient without the true testimony of the witness that I have failed to accurately transcribe.

A victim of Franco’s regime (1936–1975), like so many other Spanish poets and writers, Valente long lived in voluntary exile in Oxford, Paris, and Geneva. In such places, he was brought into contact with foreign languages and international poetry. As a translator, he rendered poetry by Paul Celan, C. P. Cavafy, Eugenio Montale, Edmond Jabès, several Englishmen (John Donne, John Keats, Dylan Thomas, Gerard Manley Hopkins), and still others. He also wrote criticism.

But whatever were the outside factors bearing on his life, his literary sensibility surely must have been inclined, from the onset, to turn away from social realism and to focus, like the English Metaphysicals, on love and metaphysics. According to Christensen, Valente “cited with approval the example of Kafka, in whose diary, he noted, ‘there are fewer than fifty lines devoted to the first world war. . . The time of the writer,’ he said, ‘is not the time of history. Although the writer, like anyone else, can be crushed by it.’”

Valente was court-martialed in absentia in 1972 for remarks critical of the Spanish military, but he remained much less drawn to politics than many of his contemporaries and predecessors. Yet there are a few exceptions among the poems selected here. One prose piece, written in Germany in 1990, cites Celan’s famous refrain “Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland” (“Death is a Master from Germany”) and announces the poet’s intention to write a political poem “to a symbolic German public.” Essentially, the piece is about creating this political poem and ends with “A girl passes by on a bicycle, tracing long forgotten esses, remnants of a boundary that can still be seen.”

Such exceptions notwithstanding, the poetics underlying Yellow Birds should therefore be distinguished from those of the preceding “Generation of 1927,” especially when otherwise different poets such as Rafael Alberti, Federico García Lorca, Jorge Guillén, Pedro Salinas, Luis Cernuda, and Vincente Aleixandre express themselves politically. Albeit, in his moving love poetry, Valente is sometimes rather close to the latter poet. In an Aleixandre-like poem, “This Image of You,” Valente emphasizes love’s (and, implicitly, poetry’s) capacity to outlive the material body:

You were at my side

and closer to me than my own senses.

[. . .]

You spoke from the heart of love

armed with its light,

on a gray afternoon of whatever day.

My youth and my words are but

the memory of your voice and your body

and this image of you will survive me.

In two very short poetic prose pieces—one a mere single sentence—Valente similarly muses on the conditions whereby death could be transcended or time vanquished:

From your inundated heart I make out your voice, the dark fog of death. It inhabits me. Not even death can tear it from me.

In the sand I draw a double parallel line as a sign of the infinite duration of this dream.

Yet nuances must be drawn between Aleixandre’s “metaphysics of the kiss” and the broader metaphysical exploration that takes place in Valente’s verse. Although he is sometimes termed a “mystical poet,” the epithet “metaphysical” is more appropriate because of his rigor and discretion. He shuns effusive flights of the imagination and tries to decipher intense moments with metaphysical implications. And his poems are little informed by Christian mysticism. The poet stands alone, or with the beloved Other, before the real world and endeavors to peer through appearances.

In contrast to earlier Spanish poets, writing poetry for Valente is—to cite Christensen—not “so much an act of communication as [. . .] a process of discovery”; moreover, such discovery is “necessarily, self-discovery.” The first poem in this selection, “To Ashes. . .,” exemplifies this process. Valente depicts himself as crossing a desert and “its secret / nameless desolation.” But he spots a distant light and realizes that he is not alone. Finally,

I touch at last this hand that shares my life

in which I am confirmed

and feel such love,

I lift it to heaven

and even if it is nothing but ashes I proclaim it: ashes.

Though all that I have obtained so far be ashes,

so it has drawn me the way of hope.

This process of discovery and self-discovery does not end with any single poem, even as the discovery of a truth does not induce him to dwell on that truth. A new quest begins. Valente ever seems underway. A poem like “Prebeginning” reveals the metaphysical movement that Valente seeks to capture and, in the fullest sense, with which he seeks to merge:

Do not stop.

And when it seems

you have been shipwrecked forever in the blind bends

of light, drink still in the dark dispossession where only

the sun is born from the radiance of night.

For it is also written that the rising

of this sun cannot stop

but goes from beginning to beginning

as beginnings have no end.

The poet searches for a kind of hope that can be “born” from within darkness and dispossession, a theme unfolding in many other poems as well. From absence, a sort of presence is perceived; out of negativity, a positive quality emerges; dispossession leads to the possession of something precious; the night has its “radiance.” In his lucid, certainly non-naïve, optimism, Valente joins French poets who are his contemporaries and whose poetry traces similar quests: Philippe Jaccottet, Yves Bonnefoy, and Pierre-Albert Jourdan similarly seek to determine, scrupulously, the conditions of hope. For Christensen, “Valente’s work can be thought of as reviving some of the concerns of the earlier modernist writers, breathing new life into a tradition that had come to seem moribund.” I would add that, like the early twentieth-century modernists, he reacts against a too facile romanticism yet respects the validity of, and sets forward with renewed rigor, the traditional romantic concern with metaphysical themes.

Up to now, Valente may have seemed to be an anti-lyrical metaphysical poet who also analyzed love without exalting it. Furthermore, as the years go by, he tends to evolve from verse to short prose, subsequently collected in the tellingly entitled volume The Singer Does Not Awaken (1992). This impression is not entirely accurate. Several poems emphasize “song,” implicitly or explicitly. Once again, Valente is non-naïve. He has deeply considered what kind of lyricism remains legitimate; that is, truthful, not deceptive; a song that moves us to truth, not a Siren’s song.

Patience and attentiveness are essential. For instance, in “The Signal,” which is a key poem selected from Memory and Signs (1960–1965), the poet awaits “the signal of the song.” In the preceding stanzas of the poem, Valente shows that this song must arise from the beauty of what might be defeat: “It is beautiful to fall, to touch the dark depths / where images are argued still / and fight desire bare-chested, the squalor of existence.” Song—the poet’s most intimate gift—must undergo a sort of initiation rite and be submitted to darkness, negativity, absence, and dispossession before it gives off the signal nevertheless fostering genuine hope. The melody might be simple, yet the notes are pure.

John Taylor has translated many French poets, most recently Jacques Dupin (Of Flies and Monkeys), Philippe Jaccottet (And, Nonetheless), Pierre-Albert Jourdan (The Straw Sandals), and Louis Calaferte (The Violet Blood of the Amethyst). He is the author of the three-volume essay collection, Paths to Contemporary French Literature, as well as Into the Heart of European Poetry. He has written eight books of poetry and short prose, including The Apocalypse Tapestries, Now the Summer Came to Pass, and If Night is Falling. He lives in France.