Fuse Jazz Review: The Enrico Rava Quintet Crackles at Berklee

Trumpeter Enrico Rava has long had a reputation as the Miles Davis of Italy, and it’s not hard to hear why—his concise, lyrical soloing, his phrasing, with its dramatic use of space, plus a golden tone that perhaps surpasses the Master’s own vulnerable, rough-hewn sound.

By Jon Garelick.

Performances in Boston by the great, Italian trumpeter Enrico Rava are rare, so the Tuesday night appearance by his quintet at the Berklee Performance Center was a major event. And there was much attendant hullabaloo. The concert was organized by the Italian Ministry of Foreign affairs in conjunction with the Berklee Global Jazz Institute (BGJI) and Umbria Jazz. There were introductory remarks by Jazz Institute managing director Marco Pignataro and faculty member John Patitucci as well as by the Italian general consul. And before the show, many audience members could be heard speaking Italian.

Two warm-up groups of BGJI students played, including a quintet that featured both Pignataro on tenor and bassist Patitucci. But the main event was Rava. The 69-year-old trumpeter has long had a reputation as the Miles Davis of Italy, and it’s not hard to hear why—his concise, lyrical soloing, his phrasing, with its dramatic use of space, plus a golden tone that perhaps surpasses the Master’s own vulnerable, rough-hewn sound. He secured his cred with early stints in New York and in collaborations with Americans Steve Lacy, Roswell Rudd, Cecil Taylor, Gil Evans, and others.

At Berklee, he was introduced by Patitucci for a couple of duo numbers, and Rava made the Miles connection immediately, launching into a sideways take of the melody of “My Funny Valentine.” Here was that spare lyricism—Patitucci easily played many more notes in his fluid accompaniment than did Rava in his solos.

But when Rava’s young band joined him, you could more readily hear what he was about. The band played nearly all originals, easily flowing from tangos and 3/4 not-quite waltzes and fast, swinging 4/4 to dreamy rubato and roiling free time. But it was those silences and the way they were filled that drove this band from moment to moment. The tension of the quintet’s restraint was made visible in the squirming of Giovanni Guidi on the piano bench.

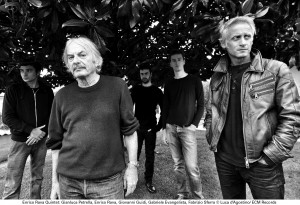

Rava has spent much of his career on ECM, where the refinement of the production can add another reverby layer of gauze to his natural impressionism. (This quintet’s most recent release is 2011’s Tribe.) But live, the band crackled. The variables of live amplified sound can be bedeviling—so credit the soundman at Berklee, or credit this band for its internal dynamics. At any rate, they certainly sounded different than the student bands. Drummer Fabrizio Sferra drives his rhythms with tonal clarity in every beat and no live-drum muddiness. Similarly, bassist Gabriele Evangelista somehow played quietly while making every note sound throughout the hall. And he didn’t play nearly as many of them per song as Patitucci. He played in a more blunt, rhythmic style that nonetheless sang as one motive built on the next to create melodic arcs. Guidi, meanwhile, earned his physical mannerisms with his mix of impressionistic chords and angled chromatic lines and blurry clusters. (He is also the author of his own fine new CD on ECM, City of Broken Dreams.) And he cut quite a figure as he leaned this way and that at the keyboard, in a long-sleeved T-shirt of broad black-and-white bands.

But it was the front line of the grey-maned Rava and trombonist Gianluca Petrella who ultimately defined the band’s sound. In Petrella, Rava has found a partner who recalls his association with Rudd—a stylist who plays in big broad strokes, whinnies, and elephant cries, but also with subtle, beautiful swing. He’s the perfect complement to Rava’s more liquid tone. The two often played in counterpoint, or Petrella would offer short punchy responses to Rava’s long-lined, lyrical phrases.

The band played for more than an hour, and for at least the first half of the show, they played without pause as they segued from one song to the next. It was almost too much of a good thing (Rava didn’t announce song titles or introduce band members until the end of the show). And for all the ensemble cohesion, I would have liked to have heard at least one extended solo—Rava or Guidi or Petralla burning over some hard, fast swing. But that’s just a quibble. This unique band is entitled to its every eccentricity, and for the listener, the rewards are many.