Short Fuse Book Review: “Harvard Square” — Precincts of a Vanished Life

What is Harvard Square today but a shopping spree waiting to happen, a student lounge, a food court? What could a novel gain by being set in that venue?

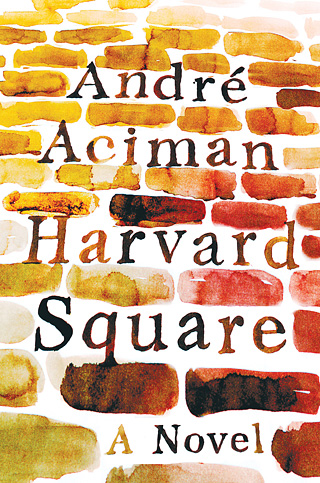

Harvard Square by André Aciman. W.W. Norton, 304 pages, $25.95.

By Harvey Blume.

Of course it’s not good literary policy to judge a book by its cover, and not much more sophisticated to judge it by its title, but that’s just what I was prepared to do with André Aciman’s novel, Harvard Square. Harvard Square holds little appeal for me, except for the squirrely chess scene in Holyoke Center, where on warm days devotees tolerate the pigeons on the boughs above who favor the area as a toilet; the debris building up and swirling around their feet; and, for lack of a better word, the crazy people who always gather around chess scenes as if to represent an aspect of the game the players themselves prefer to deny.

Aside from that, what is Harvard Square today but a shopping spree waiting to happen, a student lounge, a food court? What could a novel gain by being set in that venue? Gone are the myriad street musicians and entertainers—Latino drummers, stilt walkers, story tellers, jugglers, off-duty circus performers—who once gave the area its unique character, chased off by the store owners and managers of the mall that Harvard Square has become.

What’s left of Harvard Square is everything that Kalaj, short for Kalashnikov—so named because of his relentless “rat-tat-tat” style of verbal delivery—denounces as ersatz and “jumbo-ersatz.” Kalaj befriends and bedevils the narrator of the novel, with his high ambition to pass exams and be accepted into the priesthood of academia. Kalaj is driven no less fiercely but more narrowly: a dark-skinned, Berber cab driver, he needs a green card or will be deported, not even back to France, from which he has managed to be exiled as well, but to a hopeless life in the small, Tunisian village from which he came.

Kalaj is a chattering class unto himself, except chattering, or anything sotto voce, is alien to him: his timbre is that of “a power drill, every syllable spiked with venom, vengeance, and vitriol.” When not behind the wheel of his Checker cab, he is based at the Cafe Algiers—not today’s, airbrushed, ersatz version but that coffeehouse circa 1977. The novel opens with the narrator taking his son, applying to colleges, to Harvard, where he went to graduate school. But his memories pull him decades back to Kalaj, roiling smokes at the Algiers and launching into a rat-tat-tat about Americans: how “their extra-long cigarettes are jumbo-ersatz, their huge steak dinners with whopping all-you-can-eat salads are jumbo-ersatz, their refilled mugs of all-you-can-drink-coffee. . . their cars, their malls, their universities, even their monster television sets and spectacular big-screen epics, all, all of it, jumbo-ersatz. American women with breast implants, nose jobs, and perennially tanned figures—jumbo-ersatz. American women with smaller breasts, contact lenses, mouth spray, hair spray, nose spray, foot spray, scent spray, vaginal spray—no less ersatz.”

You can get this pitch of critique from the essays in Umberto Eco’s Travels in Hyperreality. Kalaj mounts it on his own. But his vehement critique of America is balanced, in part fueled, by his aching, if largely unspoken, need to remain here.

The narrator—like Aciman himself—is a Jew whose family was forced to flee Egypt. He perceives Kalaj as the raw version of himself—a “very rough draft. Me unmarked, unchained, unleashed, unfinished: me untrammeled, me in rags, me enraged. Me without books, without finish, without a green card. Me with a Kalashnikov.” In Kalaj he hears an “older ways of being human, raging, raging against the tide of something new that had the semblance and behavior of humanity but really wasn’t.”

Kalaj is to the narrator of Harvard Square roughly as Mouse is to Easy Rawlins in the Walter Mosley novels or as Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro) is to Charlie (Harvey Keitel) in Scorcese’s Mean Streets. Kalaj cuts closer to the bone, is more at risk, and is truthful in a way the narrator, hoping Harvard University will be his path out of Harvard Square, can’t let himself be.

The novel ends with the narrator showing his not altogether receptive son where, in his grad student days, he lived. But the book is far less concerned with fatherhood than it with brotherhood and friendship. Aciman brings some precincts of a vanished Harvard Square to life, nothing ersatz about them, and though it’s always possible to mistake one for the other, the tone when the book ends is not that of nostalgia but of heartbreak.

My son used to hang out at Harvard Square after he got suspended from Rindge & Latin. Him and his pals used to lounge conspicuously near the entrance to the T………… I went there myself sometimes — to the Cafe Algiers and a few other places. This was around 1991 and 92 ……… I imagined Harvard Square had a lot more texture before I got there, and likely a lot less these days…….. I think Harvard Square would be a good setting for a novel, but it makes for lousy title.

central sq. has a novel named after it, by george packer. (haven’t read it). kendall, porter & davis squares are, so far as i know, not novelled. someone should write a novel called “the red line” — a hot title & it covers the squares.

I wonder if anything in the novel can be better than the description here of “the crazy people who always gather around chess scenes as if to represent an aspect of the game….”

one could say that proof of the novel’s excellence is that it overcomes the lack of reference to chess.