Poetry Review: Poet Henrik Nordbrandt — Hovering Between Banality and Revelation

“Henrik Nordbrandt now holds a unique place in his homeland as its most celebrated national poet, who happens to have spent most of his adult life outside Denmark.”

When We Leave Each Other by Henrik Nordbrandt. Translated by Patrick Phillips. Open Letter Books, 165 pages, $14.95.

By Jim Kates

This volume by contemporary, Danish poet Henrik Nordbrandt does not respond to quick or obvious reading. It’s a low-keyed book that seems to defeat expectations, and translator Patrick Phillips himself bears unwitting witness to this right off the bat. In the first two pages of his introduction, Phillips maneuvers himself into a seeming contradiction, “I soon found that he was not only a subtle, funny, and moving poet, but one whose lines lent themselves to translation” and that these same lines are “difficult to render in English versions that achieve Nordbrandt’s delicate, all-important tonal shifts.”

I found a similar contradiction in reading these poems. On first acquaintance, I found Nordbrand’s verse to be breezy to the point of shallowness, an example of a kind of fashionable, flat, uncaring writing I barely tolerate in originally English texts, much less in translation:

I love to sleep around

in foreign rooms

with foreign women

and hear the rain on the roof

and hear the banana plants scraping the gutter

and hear the pipes gurgling

and a radio clicking on in the next room.

(“Sleeping Around”)

Ho hum.

But then, picking up the book at another time and opening to another page, I find the same style of versification evocative and powerful:

I would sell my fatherland

for its most beautiful rose

and be a refugee the rest of my life

if I could only see it myself

in your hand, on a spring night like this one,

as you bow your head

and pluck its petals one by one

just to keep from lifting your eyes.

(“Gesture”)

What makes the difference for me is the introduction of a second or third person into the verse, when the poems become less about the sensitivity of the narrator’s voice and more about his engagement with the world. In some of the poems, that’s exactly the revelatory movement, self-indulgent perception moves into sudden contact with real life:

The days move in one direction,

faces in the other.

Endlessly, they lend each other light.

Years later it’s hard to say

which were days

and which were faces . . .

And the distance between the two

feels more impossible to cross

day after day, face after face.

That’s what I see when I look into your face

these late, bright days in March.

(“Late Days in March”)

Which makes me suspect that my own variation in reaction to these poems has to do with patience (or the lack of it)—a quiet quality demanded of the reader.

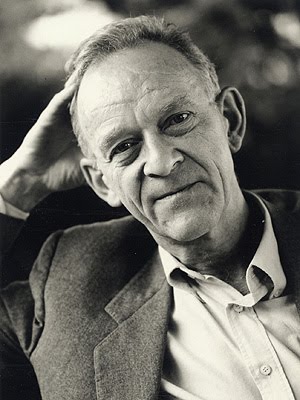

Poet Henrik Nordbrandt — He has published over 30 books, including poetry, essays, translations, a novel, and a cookbook. In 2000, he was awarded the Nordic Council Literature Prize.

There is something in this relationship between writer and reader that borders on being stereotypically Danish. A foreigner living in Copenhagen once told me that the reason Danes are ranked among the most contented of peoples is that they have such low expectations. This is a negative way of expressing what I think the poet represents more positively, perhaps because, as Phillips puts it, “Nordbrandt now holds a unique place in his homeland as its most celebrated national poet, who happens to have spent most of his adult life outside Denmark.” (He left Denmark in 1966 and has hardly been back since.) The poet sets up low expectations and more than fulfills them. He begins all too comfortably at home and then goes away.

When We Leave Each Other includes the original Danish text of a selection of poems from 1969 through 2007, a fairly wide offering from a half dozen books. Phillips seems to have caught many of the the patterns of the originals, but the bilingual format sets its own inviting standard. In “Thalassa,” Phillips renders one line, “Harbor doesn’t rhyme with amber,” but it’s clear that the original is an exact rhyme: Hav with rav. Until you pay attention to the left-hand page, you won’t pick up the irony of the strict rhyme-that-doesn’t-rhyme. You can see the translator is trying to get there with harbor/amber, but it doesn’t quite work by itself. The original bails him out.

The book could have done with a few notes. When you see a title like “Cehennem Ve Cennet,” it doesn’t look like Danish, and it’s not translated into English on the right-hand page. Am I the only reader who has to flee to Google to find out that this is Turkish, and the poem describes two sinkholes in the Toros Mountains? But most of the poems are general and clear enough. And the book ends on the same compelling note, hovering between banality and revelation, as it began:

What looked like a mask

was only itself:

. . .

Their expressions so clear

and inscrutable, like tarot cards,

that for an instant you can see the future

as clearly

as if it lay before you.

(“The First Day of Late Summer”)

Tagged: Henrik Nordbrandt, Norwegian Poetry, Open Letter Books, Patrick Phillips, translation