Film Commentary: “Metropolis” Restored

And why [are] men bound beneath the heavens in a reptile form/ A worm of sixty winters creeping on the dusky ground? — Tiriel, William Blake

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis: Bigger, Better, and Back in Boston

Metropolis. Directed by Fritz Lang. Written by Lang and Thea Von Harbou. With Gustav Fröhlich, Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel, Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Erwin Biswanger, Theodor Loos, Fritz Rasp, and Heinrich George. Original music score by Gottfried Huppertz. 149 minutes. At the Coolidge Corner Cinema, Brookline, MA, June 4 through 10.

By Bill Marx

With the discovery of about 25 minutes of missing footage, one of the great silent films, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, becomes bigger, brassier, and better. Thus the week-long run at the Coolidge Corner Cinema of the sharp-looking restored version should be a mandatory treat for anyone who loves movies. Of course, the expanded print will be nirvana for silent film buffs, especially those already grasping tickets for the sold out opening night this Friday, which will have the Alloy Orchestra accompanying the screening with its no doubt rousing original score—a divine concatenation of banging, bonging, and boogieing. The film will be accompanied by its original orchestral score for the rest of the week.

It is marvelous to have the new footage, and some of the material clears up an enigma or two, especially the mysterious reasons behind the death wish of the film’s mad scientist, the angst-ridden Rotwang. But some critics, stuck in hype mode, have overreacted to the find. “Can anything be more satisfying than finding the last missing pieces to a puzzle, the critical elements that make the whole thing make sense at last?” asks Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times‘s film critic. Well, yes—letting the film remain as astonishingly wacko as it was in 1927 when it premiered.

Metropolis would not be nearly as exciting or impressive if its campy, mythopoetic doings made a whit of genuine sense. This is the still flashy granddaddy of the myopic, “visionary,” science fiction film genre, its crazed glory influencing countless unhinged looks into the future, from Things to Come and Forbidden Planet to 2001 and Blade Runner. None of these films bear close rational scrutiny in terms of their ideas or plot. Even with the new footage, Metropolis remains as weird and inexplicable as ever. Allegorical chaos is the secret behind its success, a vital part of its pop prophetic cache. In the 1920s and now (think Avatar), eye-popping visual kitsch overwhelms inane story and banal philosophical themes.

For example, one question the new footage doesn’t answer is the lack of an effective police force in Metropolis. Tyrannical CEO Freder Fredersen uses Rotwang’s evil robot version of the saintly Marie to rile up the downtrodden workers so that their resistance will be crushed. (She also whips middle management types into a homicidal, sexual frenzy, though they have been perfectly docile. The bureaucrats just can’t win.) But nowhere in the film is there a cop, even to hand out tickets to flying taxis. Nobody is around to bust heads, so when the city runs wild how is Fredersen planning to stop the riot? But then why undermine the workers to the point of murderous violence in the first place?

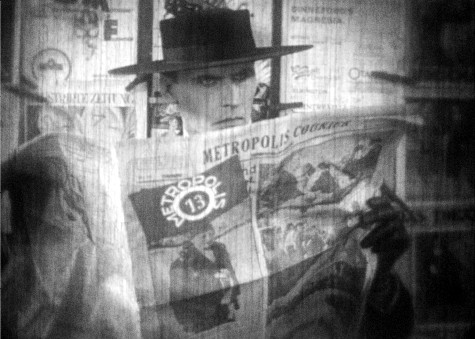

Metropolis: Some of the restored footage features Fritz Rasp as the sneaky spy Slim

Given where Germany was going in the near future, the omission of brutal law enforcement is revealing. Of course, the film’s principle of self-policing gives us the amazing opening images, where the workers trudge off to their 10-hour days as tightly-wound automatons, their defeated heads hung low. There’s no need for bully clubs—obedience is a Pavlovian response. No doubt Orwell had these pictures of “mind-forged manacles” in mind when he wrote 1984. Metropolis’s notion of a spiritual anti-utopia has shaped futuristic literature as well.

Still, the restored footage gives us more of what serves as the sadistic strong arm of the law in Metropolis. There is additional footage featuring the creepy skulduggery of Slim, a wily management spy who reports back to Fredersen. He seems to have a change of heart by the end of the film, reminding his boss that all men are brothers, but we don’t see what brought this birth of a conscience about.

More illuminating are “new” scenes that focus on the shrine to the deceased Hel, the woman Rotwang lusted for but the wealthy Fredersen married. The connection with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is cemented with views of the ornate monument in Rotwang’s home: like the earlier mad scientist, Rotwang can not accept the loss of his beloved. (Frankenstein could not bear his mother’s death.) Technology serves as an anguished riposte to death, a sick dream of Godhood that is defeated, logically enough, at a cathedral, where the workers and their children receive their “resurrection” from a chastened Fredersen.

The shrine to the dead ironically links the emotionally-stunted lives of Rotwang and Fredersen—their dreams of power are destructive because they are based on impossible desires for immortality, the control of time itself (note Lang’s imaginative use of clocks as signs of physical imprisonment). The director’s deft control of gargantuan imagery and crowds remains as exhilarating as ever—the added 25 minutes of real estate reinforces Metropolis’s position as one of cinema’s cities on a hill.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

I’ve been waiting for this ever since the lost footage was found in a vault a couple of years back!

Metropolis, apart from its stunning city views which last only a few minutes, is about the most boring pic ever produced. Particularly when compared to contemporary Russian and French cinema.