Visual Arts Review: “City Of Work” — A Satirically Dystopic Vision of The Daily Grind

Artist Michael Lewy’s comprehensive, clever, and surprisingly humorous take on an imaginary experimental settlement explores the ramifications of having human potential promptly assessed and harnessed for work and work alone.

City of Work by Michael Lewy. At the Boston Cyberarts Gallery, 141 Green St., Jamaica Plain, MA, through February 17. Gallery Hours: Friday, Saturday, and Sunday 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. The gallery is on the ground floor level of the Green Street train stop on the Orange line.

By Margaret Weigel

There are days at work when one experiences moments of personal satisfaction, meaning, and (very occasionally) joy. Most of the time, however, work is a means to end, an activity that puts food on the table and keeps the lights on. Imagine a world, then, where work exists as a self-sustaining, parasitic corporation that obliterates any division between public and private, work and leisure, the individual and the collective. Welcome to the City of Work, artist Michael Lewy’s comprehensive, clever, and surprisingly humorous take on an imaginary experimental settlement where human potential is promptly assessed and harnessed for work and work alone.

Envisioning a hilarious totalitarian world—where a workaholic state holds total authority over the society and seeks to control all aspects of public and private life—may be the most effective insult to such a heinous regime. Lewy leavens City of Work with wry humor that skewers a number of business culture sacred cows and highlights the absurdity of work for work’s sake. He also leaves the viewer worrying about personal agency, particularly the encroachment of work and work processes on leisure time, creativity, and the freedom to be human. Lewy has also created a website for the project, but it is less comprehensive than the show at the Boston CyberArts gallery space.

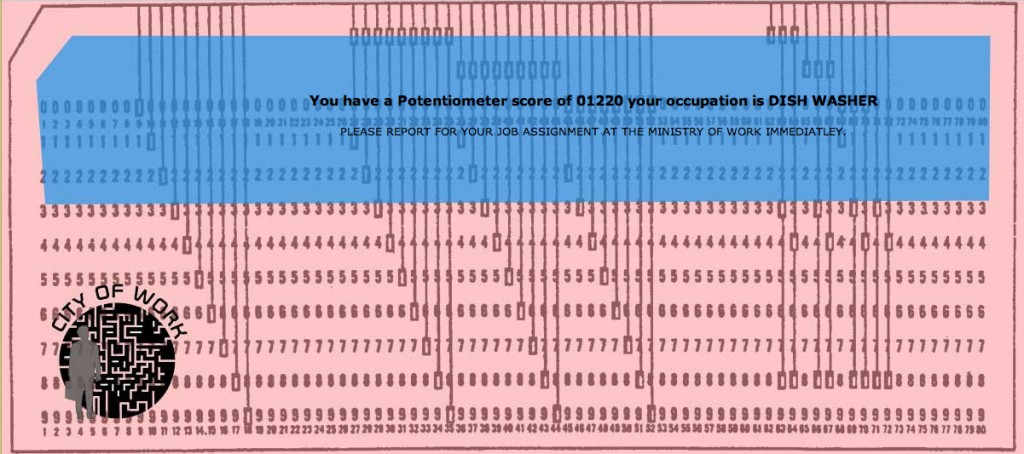

City of Work greets the visitor with an “orientation video” that describes the characteristics of the imaginary settlement (nestled somewhere in New Mexico) and introduces the brilliant and revered Marcus Sterling L’amour, founder and CEO of Omnipresent Industries. The video informs the visitor about the City of Work intake process, which includes filling out some paperwork—“we anticipate that this will take you between three and five hours to complete”—and completing the Potentiometer aptitude test at the Human Potential Center for occupational assignment.

Situated between the orientation video and the Human Potential Center computer station is the main gallery space filled with an array of Omnipresent Industries ephemera. Two large video screens flank the far ends of the room. One shows a solitary worker busily moving between four computer stations in a generic office space but with little to show for it, as if the job was to perpetuate the job and little else.

A common element of totalitarian regimes is a charismatic leader, and Omnipresent Industries does its best to frame its CEO as an object of adoration and wisdom. One of the two longer gallery walls was painted a very vibrant shade of yellow and sported gold-framed images of Mr. L’amour as well as some of his inspirational aphorisms, including “note to self: have grindstone installed in office,” “it takes many hands to make a basket—but just one to fill it with money,” and “it’s not what you say—it’s what people hear.” Icing on this cake of corporate mockery comes in the form of two potted plants gracing the display.

Across the gallery from the L’Amour Appreciation Wall are a series of informational posters and aspirational blueprints laying out Omnipresent Industries’s plans for perpetual growth. The posters, though, are where much of Lewy’s concepts blossom. The works are not notable for their production or stylistic value but for how they casually convey the disturbing reality of life in the City of Work.

Lunchtime is reconceived as a lawless time: “Don’t get caught stealing. Be safe. Eat at your desk.” Unemployment in the City of Work is illegal. A poster, featuring helmeted surveillance personnel/policemen, serves as a helpful reminder that “It’s Against the Law to Be Out Of Work.” But what if you are anyway? The City of Work has a solution: “Welcome to your new home: The Unemployment Relocation Camp.”

Lewy’s Mad Hatter reinvention of modern work culture and bureaucracy is fully realized in his Potentiometer aptitude test at the Human Potential Center for occupational assignment. The test consists of 10 questions that perfectly mirror the cloudy logic proffered by the quantitative personality and assessment tests corporations and testing organizations rely upon. See some of my answers below:

The first time I completed the Potentiometer, I was assessed as being a good fit for the job of Press Operator. The next two times I took the test, I didn’t answer any of the questions and was awarded for my insouciance with Lawyer and Dish Washer work assignments.

In Lewy’s conception, the individual immediately surrenders any personal agency or down time in the service of the corporation. Some may argue that current conditions in America are not enormously different from those described in the “City of Work.” As Lewy points out in the show’s press release, labor research Juliet Schor’s book The Overworked American detailed how Americans work a month longer a year in 1990 than in 1970, and our first world counterparts typically enjoy generous vacation benefits and shorter workweeks than we do. Why are we such slaves to work? Are we willing to give up our free time in its service? And will we still be shipped off to Unemployment Relocation Camp even if we play by the rules and eat lunch at our desks?

The curator told me that the artist holds an administrative desk job. I can only hope that he conceived and produced much of City of Work on his employer’s dime.