Theater Review: “Tales From Ovid” — An Embarrassment of Riches

Director Meg Taintor’s demands on her five young actors—three women and two men—are very high, requiring not only daring but physical stamina and skill, dance training, mime training, fight training, and musicianship as well as dramatic power.

Ted Hughes’ Tales From Ovid. Adapted by Tim Supple and Simon Reade. Based on Tales From Ovid by Ted Hughes. Directed by Meg Taintor. Staged by Whistler in the Dark. At the Jackie Liebergott Black Box in the Paramount Center (559 Washington Street, Boston, MA), through November 18.

By Helen Epstein

If you’re interested in young, state-of-the-art theater, performers courting danger within spitting distance of your seat, a director culling from dance, circus, and story-telling and bringing twenty-first century technology to still-stirring first century material, go see Tales from Ovid.

Ovid’s Metamorphorses, a narrative poem in 15 parts composed at the dawn of the Christian era, has served as artistic inspiration and source material for writers, visual artists, and composers over 2000 years. Some of its story lines—Pygmalion, Pyramus and Thisbe, Narcissus, Midas—are familiar from readings in Greek mythology; others—like Myrrha and Tereus—are less familiar and shock even in 2012.

In the 1990s, British poet Ted Hughes composed new translations of 24 poems from this compendium. His excitement about the project is palpable in his introduction to the work: “Ovid was born the year after the death of Julius Caesar . . . (and) completed the Metamorphoses around the time of the birth of Christ . . . an account of how from the beginning of the world right down to his own time bodies had been magically changed, by the power of the gods, into other bodies.”

“This licensed him to take a wide sweep through the teeming underworld or overworld of Romanised Greek myth and legend, The rightman had met the right material at the right moment. The Metamorphoses was a success in its own day. During the Middle Ages throughout the Christian West, it became the most popular work from the classical era, a source-book of imagery and situation for artists, poets and the life of high culture.”

There have been theatrical adaptations of the work all over the world. Most recently in the United States, Mary Zimmerman wrote and directed her own theater piece drawn from the poem. In 2010 Boston’s then five-year-old Whistler in the Dark Company mounted a production using Ted Supple and Simon Reade’s adaptation of 10 of Hughes’s poems. This production is a second staging (at the invitation of Arts Emerson) in the larger setting of the 150-seat theater space.

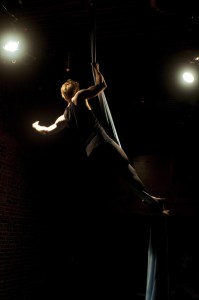

There is no set except for the two columns of pale silk material suspended from the rafters that suggest classical Greece, become sails and clouds and hammocks, provide the five actor/acrobats with a way to move between heaven and earth, and effect their transformations. Decades of Cirque du Soleil have made spectacular aerial stunts and startling images of the kind the Whistler perform almost a cliché, but Cirque now performs in mega-halls. When uncanny extensions into space and sudden falls come so close to your seat, it raises the ante and your blood pressure.

Director Meg Taintor’s demands on her five young actors—three women and two men—are very high, requiring not only daring but physical stamina and skill, dance training, mime training, fight training, and musicianship as well as dramatic power. Costumed simply in black dancers’ leotards and leggings, they divide up 30 roles with a refreshing indifference to gender (I thought, gender-blind casting!) and perform cohesively and persuasively as sun and stars, various animals, gods and humans.

After the show is over, you are left with many haunting visual and auditory images: Atalanta racing to outrun her beaux; Arachne dangling from her spider’s web; King Cinyras lounging in his hammock; Echo and her echoes; the sounds of whispering and babbling after Filomela’s tongue is ripped out by her rapist.

Unfortunately some of Ovid’s poetry and Ted Hughes’s blunt translation are lost in the tumult. The Whistlers, versatile as they are, need more voice training and work in their speaking of the texts, such as “Man has made new laws to deprive Nature of its nature.” The latter was one of the few lines that stood out loud and clear. If you’re not already familiar with the myths, both the story and the beauty of the poetry sometimes get lost. While the choreography and the physicality of the actors never flags, the delivery of their lines is uneven.

I very much admire Meg Taintor’s plucky direction and her choice of design team, starting with the Aerial Silks and enhancing their use with innovative sound design, casting a violinist/ actor, and using the ensemble to produce choral humming singing and percussive tools (including their own bodies) to good advantage. Tales from Ovid provides an embarrassment of riches and a testament to the staying power of good theater.

Helen Epstein is the author of Joe Papp: An American Life and other books about the performing arts. SHE has written both memoir and biography and publishes classics of the genres at Plunkett Lake Press.

Tagged: ArtsEmerson, Culture Vulture, Ted Hughes' Tales From Ovid