Book Review: The Overthrow of Pessimism — Sherman Alexie’s Song of Redemption

Grappling with one’s identity—complicated by the relationships between tradition and modernism, cultural history and the process of assimilation—is central to most of Sherman Alexie’s stories, and his exploration of these complexities is compelling and illuminating.

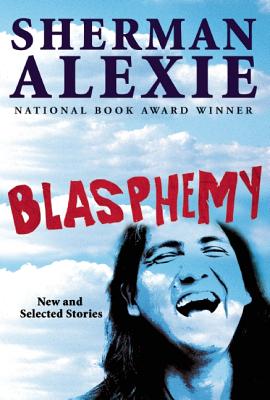

Blasphemy: New and Selected Stories by Sherman Alexie. Grove Press, 480 pages, $27.

By Kevin Hong

Sherman Alexie’s characters live in the thrall of pessimism. A sense of hopelessness precedes them; as each rushes to his or her end, the reader comes to see, and perhaps to believe, that in this world, or at least Alexie’s, one’s fate is tied up with futility. As Eugene Thacker writes in his essay-cum-elegy “Cosmic Pessimism,” “failure is a question of ‘when,’ not ‘if’—failure as a metaphysical principle.” If failure operates as the governing force in our lives, then “failure becomes fatality,” and finally, “Futility transforms the act of thinking into a zero-sum game.” There is a musicality to those words that makes pessimism a kind of poetry, a “poetry written in the graveyard of philosophy.”

In Blasphemy, Alexie’s most recent volume of new and selected short stories, loneliness, pain, and death pervade life. Every action has a greater and opposite reaction. The characters in Blasphemy are pugnacious, stubborn, and unsentimental; they are unapologetic in their race toward destruction. There’s Junior in “Cry Cry Cry,” the book’s opening story; after graduating from cocaine to meth to heroine, Junior goes to jail, where he is physically and sexually abused. There are the men in “The Toughest Indian in the World”—one a fighter whose hands are scarred and gnarled from exchanging blows and the other a man with no sense of direction or belonging. To them, the sky is a void, what the narrator calls “nothing more than white tombstones scattered across a dark graveyard.” And there is the homeless man in “What You Pawn I Will Redeem,” who tries to make 999 dollars in 24 hours to redeem his grandmother’s stolen powwow regalia. You can guess: any money he makes is spent on alcohol.

Minor characters, too—the Aleuts who have been waiting for a boat to pick them up for 11 years; Junior’s wife, who after being abused by Junior, leaves him for a another man who continues to abuse her; the boy who is pummeled to a pulp by the fighter, “too beaten to fight back, but too strong to fall down.” As the narrator of “Cry Cry Cry” says,

Yeah, we Indians are addicting. You have to be careful around us because we’ll teach you how to cry epic tears and you’ll never want to stop.

Blasphemy is just as much a collection as a selection of powerful individual stories. The book gives wonderfully diverse voices to the Spokane and Coeur d’Alene and Lummi Indian experiences. The stories commune across its pages: jokes are repeated like leitmotifs; characters occupy themselves with similar hobbies; they face the same failures. They listen to the same music; they laugh sardonically at themselves; they die of the same causes:

“My dad just got his feet cut off,” I said.

“Diabetes?”

“And vodka.”

“Vodka straight up or with a nostalgia chaser?”

“Both.”

“Natural causes for an Indian.”

“Yep.”

There wasn’t much to say after that.

– “War Dances”

If these characters met each other in a bar, they’d buy each other drinks. They would sing songs together and dance together and then either fight or sleep together. And yes, all of this does happen in Blasphemy’s pages. These people are bound together by loneliness and nostalgia, hardship, and grief.

The way these stories echo and converse with each other not only makes each character part of a larger experience, but it also burdens each with the weight of the Native American culture. The stakes are not only personal but also societal. Grappling with one’s identity—complicated by the relationships between tradition and modernism, cultural history and the process of assimilation—is central to most of these stories, and Alexie’s exploration of these complexities is compelling and illuminating.

Some characters identify strongly with their tribe and harden themselves against the world outside the reservation. The narrator of “The Toughest Indian in the World” only stops for Indian hitchhikers on the highway, remembering his father’s warning against whites. Jimmy, in “Protest,” insists on being called “White Eagle Feather”; the irony is that his skin is so light that nobody takes him seriously. In “Cry Cry Cry,” the narrator uses the history of the oppression of his people in an attempt to understand his friend’s sexual abuse and subsequent crime:

Maybe at that point, all Junior could see was the Aryan who’d raped him a thousand times. Maybe Junior could only see the white lightning of colonialism. I don’t mean to get so intellectual, but I’m trying to understand.

Sometimes characters no longer identify with Indian culture. The narrator of “Do You Know Where I Am?” recognizes the irony of his success in the American system (Alexie himself left the Spokane Indian Reservation in which he grew up to pursue higher education):

Sure, we’d been thoroughly defeated by white culture, but dang it, we were conquered and assimilated National Merit Scholars in St. Junior’s English honors department.

The joke is even funnier since Junior is one of the stereotypical names given to Native American boys—something we see in “Cry Cry Cry.” In fact, this narrator is so estranged from his heritage that he comes to see the Spokane Reservation as “ordinary and magical, like a sedate version of Disneyland.”

In some cases, Native American tradition collides with and confuses personal strife. In “What Ever Happened to Frank Snake Church,” Frank, a talented basketball player with a chance to go to college on a full scholarship, gives up the sport when his mother dies. When his father passes many years later, he takes it up again and plays on the streets:

“Preacher,” Frank said, “it’s true. . . . This is, like, a mission or something. My mom and dad are dead. I’m playing to honor them. It’s an Indian thing.”

But Frank’s ritualistic act is complicated by an inner conflict that Preacher brings to the fore:

“That’s crap,” [Preacher] said. And it’s racist crap at that. What makes you think your pain is so special, so different from anybody else’s pain? . . . You’re playing to remember yourself. You’re playing because of some of that nostalgia. And nostalgia is a cancer. Nostalgia will fill your heart up with tumors. Yeah, yeah, yeah, that’s what you are. You’re just an old fart dying of terminal nostalgia.”

In this story, Preacher’s name is ironic because of his trash-talking persona on the basketball court. But Preacher’s diagnosis of Frank is also an accurate diagnosis of the book, throughout which the cancer of nostalgia has metastasized. The echoes that connect these characters are also echoes of the distant and irretrievable past. The people that they wish they could be are the warriors and legendary powwow dancers of previous lives.

Blasphemy is haunted by ghosts: there is so much death and sickness that characters write obituaries for obituary writers. The grandness of the American Indian tradition is tinged with bitterness and irony. As the narrator of “War Dances” says, “The Indian world is filled with charlatans, men and women who pretended—hell, who might have come to believe—that they were holy.” The equivalent of the mystic in the modern day is the homeless man who drinks himself into oblivion and wakes up sprawled across train tracks. Nostalgia is a song tied up with the Native American identity; it resonates in each character just as it eats away at his or her spirit. It fills the gaps between Alexie’s bold, simple sentences: each line forges ahead in narrative while belying the understated emotions of the characters that stoically face defeat.

Alexie’s belligerent humor initially seems like a rejection of nostalgia, but it is ultimately a disguise for that sentimental strain:

Yeah, we could laugh about it. What else were we going to do? If you sing the first note of a death song while you’re in prison, you’ll soon be singing the whole damn song every damn day.

– “Cry Cry Cry”

Laughter to Alexie is a necessary, but temporary, salve. In this community of nostalgia, it is the only thing between failure and despair. In Thacker’s essay, laughter is “a yes-saying to the worst,” that is, both an acceptance of and a delight in the futility of the world. “Crying, laughing, sleeping—what other responses are adequate to a life that is so indifferent?”

But despite all of the heartbreak in this book, Blasphemy ultimately manages to shake itself of the thrall of pessimism that could so easily poison it. Where there is nostalgia, there is hope of redemption, and where there is laughter, there is the will to go on. In a book that takes “blasphemy” as its name, in which tradition and relationships and dreams are dismantled, redemption comes in the form of the sacred—moments in which characters turn to faith, secular or spiritual, and hold fast to their belief. In “The Approximate Size of My Favorite Tumor,” a woman who has left her dying lover comes back to him to help him die. In “Night People,” two insomniacs share an intimate moment of understanding in a nail salon before returning to their lives. In “Do You Know Where I Am?” the narrator reaffirms his love for and devotion to his wife while she lies on her deathbed.

One could accuse Alexie of excessive sentimentality; perhaps his characters are too stubbornly or naively hopeful. But I see this hope as an inner strength that reminded me of Faulkner’s speech at the Nobel Banquet:

I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged . . . that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. . . . I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal . . . because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.

It is the fictionist’s job to look up, “to help man endure by lifting his heart,” to believe in something, even if the belief is in the “infinite and ridiculous faith of other people” (“War Dances”). Without this belief, Alexie would have written a book about his disenchantment with his own people, consigning them to doom. Instead, he refuses to succumb to pessimism’s refusal of life. The heart affirms that it is human, and the spirit remembers where it comes from.

Blasphemy’s opening story ends with a traditional powwow, the narrator dancing “for what we Indians used to be and who we might become again.” After close to 500 pages of hardship and heartbreak, this hope is reignited on the last page; Jackson Jackson dances in the midst of traffic, invoking the tradition and the pneuma of the Indian people. His tale of redemption transcends the genre of realism; it is a modern-day quest, Odysseus’s return home.

“Teach me to laugh through tears,” Thacker writes. He should have read Sherman Alexie.

I think this is a breakthrough book for a writer who didn’t even need a breakthrough. But this collection is not weighed down by sadness, and not, as you say, poisoned by pessimism; there is a strange lightness that Alexie has achieved. You come away from the stories not burdened, but feeling strengthened to go on with your own messed-up life. An author who dares to go to the heart of human resignation/despair/hope/humor should not be accused by other reviewers of being “sentimental.”

You’re right.