Book Review: “The Greatcoat” – A Great Ghost Story?

By Roberta Silman

I can say, without equivocation, that Helen Dunmore’s novel The Greatcoat is no The Turn of the Screw.

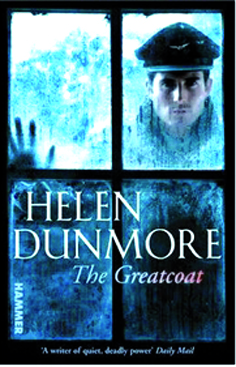

The Greatcoat by Helen Dunmore. Atlantic Monthly Press, 208 pages, $24.

Helen Dunmore is well known in her native England for her novels, short stories, and children’s books. She has won the prestigious Orange Prize and been short and long listed for other prizes; her work has been compared to that of Tolstoy, Emily Bronte, and Virginia Woolf, and this newest short novel has been called by English critics “a perfect ghost story,” reminiscent of both Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black and Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. Although I remember that a fuss was made over the Black book, I didn’t read it. But I can say, without equivocation, that Dunmore’s novel The Greatcoat is no The Turn of the Screw. Speaking about those two books in the same sentence is sacrilege because The Greatcoat is a particular kind of British kitsch that a favorite college professor of mine simply called “holly-golly.”

But before I get into the specifics of Dunmore’s latest novel, I think it worth talking about the notion of the unreliable narrator, which has had some real purchase lately with the publication of Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending and whose best examples in the past were Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, and James’s masterpiece, The Turn of the Screw. Fundamentally, these novels are really puzzles that have many layers that we have to work through to get at the truth only to discover—when we have peeled all the layers—that the truth still eludes us. That is why we are still discussing them so many years after they were published.

What sets them apart are the profound questions the author is attempting to answer: not only what really happened but the intensely important problems of good and evil that are the very foundation of all three novels. For if we write what we don’t understand or are afraid of, as I think serious writers do, the stakes are huge. Are Miles and Flora evil beings, or have they been corrupted by Peter Quint and his ghost? Or is Miss Jessel crazy? These questions have plagued not only readers but also Benjamin Britten who wrote an opera based on The Turn of the Screw. Profound questions can also be asked about the two Catherines and Heathcliff and Nellie Dean in Wuthering Heights, which has inspired great acting in several movie versions. And perhaps the most puzzling of all, because it is about marriage and adultery, are the complicated relationships of the two couples in The Good Soldier, which will surely, someday, have its day in other artistic forms. And that is because these characters and their stories haunt the reader long after the books have been closed.

To write such long-lived work requires precision and enormous talent on the part of the writer. Based on The Greatcoat, I can report that Dunmore simply hasn’t got the goods. She had a terrific idea ,which goes briefly like this: a young woman named Isabel who is married to doctor in a Yorkshire town in 1952 is bored and lonely and depressed by the penetrating cold that characterizes an English winter (having lived there, I can attest to that truth). In an attempt to get warm in bed, she finds a greatcoat folded in the closet of their rented flat, and before she knows it, is involved in an affair with the owner of the coat, a World War II RAF pilot who comes to her flat with no warning and leaves, also with no warning. To up the ante, Dunmore also starts the book with a prologue that, we eventually realize, is the pilot setting off on his final mission.

Dunmore is a fluid writer who sets up Isabel as the quintessential unreliable narrator, and in the beginning, it seems to work. But then the whole thing devolves into a mish-mash, which I won’t give away, but which could have been avoided if Dunmore had figured out a better way to tell this story. One possible way would have been to have multiple points of view and not have Isabel carry the whole burden. (There are occasional glimpses into the mind of her husband, Philip, and that supposedly cliff-hanging prologue, but none of it really works.) This is a shame because the ingredients are there—the war, the small, Yorkshire town with its judgmental people observing another woman (a wife and mother) involved in an intense affair with Alec. But because all this information is filtered through Isabel’s fevered brain years later, my reaction was confusion and a kind of exasperation that comes when you feel that the writer isn’t in complete command of her material. Here is Isabel, quite far into the story, assessing her position:

The whole weight of the house seemed to press down on her. She was afraid again. Alec’s words echoed in her head, but now they were more than a promise: I’ll knock on the window, Swear you won’t go to sleep. She saw his eyes on her. Her heart clenched at the remembered expression on his face. He was outside in the dark and the wind, staring in at the warm, lit world. Whatever happened, she knew that Alec would come for her, and she would slip into the other life again, her mind clouded with memories that weren’t hers, her body moving to rhythms it had learned elsewhere. Nothing on earth could stop him from coming, or her from becoming the other woman, once he was there. There was no one strong enough to hold her back.

You have to be possessed of great skill to make a main character possess convincingly “memories that weren’t hers.” Although Dunmore makes Isabel unstable enough for the reader to wonder, and there are coincidences and disappearing gin and all sorts of gimmicks to persuade us of Isabel’s plight, it somehow feels like an exercise. Almost as if Dunmore had said to herself, “I think it’s time to write a ghost story with a sexy twist.”

There is nothing organic about this novel, no sense that the characters really matter, nothing that will change your angle of vision as you read. Instead, you feel almost constantly the author’s heavy hand, and the real pity is that the one character who could have brought the book to another level, the landlady, becomes more a device than a person. Indeed, I felt as I closed this book that the author had lost interest or simply hadn’t thought it worth working hard enough to create the rounded and complex characters her original idea deserved.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She writes regularly for The Arts Fuse and can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.