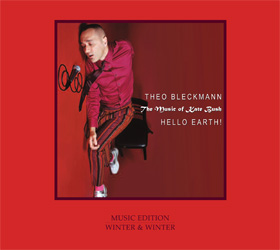

Jazz Review: Vocal Chameleon Theo Bleckmann Sings Kate Bush

A critically acclaimed player in the New York avant-garde scene, Theo Bleckmann is clearly a Kate Bush connoisseur, and his commentary on her work was as compelling as the performances.

Bleckmann on Bush. At the Regattabar, Cambridge, MA, June 21.

By Steve Mossberg

Singer-songwriter Kate Bush is a hard artist to pin down. Overwhelmed by the pressure and scrutiny she attracted as a teen superstar, she retired from the stage after only one concert tour. Bush divided listeners with her strange, squeaky-high voice, eccentric lyrics, and bizarre modern dance routines. Her influence is reflected in the work of three decades of musicians from Tori Amos to Andre 3000 to Joanna Newsom, but her physical presence is nearly never felt by her most adoring cult followers. Theo Bleckmann’s “Hello Earth” project (and album) is a hyper-modern, jazz exploration of the vital work of an artistic recluse and the accompanying tour is a chance for many to see what they’ve waited years for: a Kate Bush concert.

At the Regattabar Thursday night, the air of anticipation was to be expected. Bleckmann, a critically acclaimed player in the New York avant-garde scene, is a compelling vocal chameleon. Using a machine to sample and layer his eerie, crystalline, vibrato-free voice, he created clouds of sound that were equal or greater in texture to the vintage synthesizer sweeps of Bush’s original material. Accompanying himself in this fashion, he brought a heightened sense of depth and intimacy to radio hits like “Running Up That Hill” and “This Woman’s Work.” When singing lead lines, it was not uncommon to hear him slide a low note into Tuvan throat singing or to create alien sounds by using his hand as a trumpet mute.

Bleckmann’s cohorts were up to the challenge, bringing versatility to his often surprising and difficult arrangements. Caleb Burhans, an accomplished, new-music violinist, readily swapped an electric guitar in for his souped-up fiddle, driving the sound of both instruments through the same Fender amplifier. Canadian bassist and composer Chris Tarry played sensitively and minimally in tandem with drummer/producer Ben Wittman, giving Bleckmann’s performances both ample breathing room and the necessary bite when needed. Henry Hey, Bleckmann’s pianist, is a highly creative jazz voice who is also respected for his accomplished technique in the field but spends most of his time working with pop and rock musicians. He played with equal aplomb as a straight accompanist and as an improviser, unleashing piano solos of varied character and invention throughout the concert.

Beckmann singing Bush at Cambridge’s Regattabar. He drew out kernels of truth and beauty. Photo: Kristophe Diaz

Bleckmann is clearly a Bush connoisseur, and his commentary on her work was as compelling as the performances. He freely rattled off release dates and remarked on the coolness of the cover art on her original vinyl records, but he also spoke eloquently about color symbolism and gender themes in her lyrics. Bush’s texts, though poignant and creative, are frequently flawed by inexperience—a result of the pressure to produce too much music at a young age. Bleckmann drew out kernels of truth and beauty from immature works such as “Wuthering Heights” and “Wow” by darkening their arrangements, playing down the most awkward passages, and emphasizing the emotional weight of unlikely phrases on the periphery.

Bleckmann daringly transformed his own physical voice and Bush’s artistic vision with impressive and often unsettling results. “Saxophone Song,” off her debut recording The Kick Inside, is a naive teenage love poem set in a smoky jazz club she likely never entered. The group replaced her original power-pop arrangement with a blistering, dissonant jazz rant, her quaint faux-scat transformed into a mercurial bebop line by Hey and the vocalist. Using a nasal, vaudeville approach, Bleckmann led the combo through a jarring, carnival-like reimagining of “Suspended in Gaffa,” with Burhans taking the vocal hook in a bright boy-soprano tone. “Violin,” a painfully dated, classic-rock oddity in which Bush imitated the sound of the instrument with her voice, became a hardcore punk fist-pumper in the band’s hands. The real violinist screamed on his instrument like a guitar hero, and Bleckmann himself barked out the words through a demonic-sounding electronic filter.

As a counterpoint to the grotesque humor and satire, Bleckmann included several selections from Bush’s 1985 suite “The Ninth Wave,” which deals with such dark themes such as drowning in the ocean, being trapped under ice, and looking wistfully down at the earth from outer space. In these moments, his band often disappeared completely or joined in ambient sound making while he took complete command of the Regattabar. His vocal delivery on this material, while warm and intimate, was by no means soft. Earnestness without sentiment is a hallmark of Bleckmann’s style, and in this case, it served Bush’s material flawlessly.

To end the concert, Bleckmann chose “Love and Anger,” a later work of striking directness, which Bush wasn’t particularly fond of herself. The band played this one straight, forcing the audience to tune into its simple lyric about repairing a broken personal relationship. When he repeated the line “we’re building a house of the future together” over and over, it symbolized his own challenging forays in tying up of the loose ends in Bush’s brilliant but problematic repertoire.