CD Review: Basya Schechter Sings “Songs of Wonder”

This CD marks a turning point: a solo effort by Basya Schechter with outstanding back-up by a wide range of musicians that features music based on the Yiddish poetry of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Songs of Wonder by Basya Schechter. Tzadik.

By Jim Ball

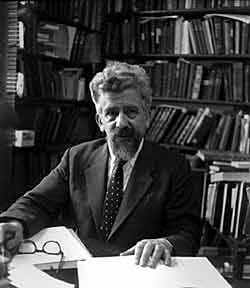

Basya Schechter singing tunes from SONGS OF WONDER at the Boston Jewish Music Festival. Photo: Jim Ball

I’ve been entranced by Basya Schechter’s latest CD and had the delight of hearing this music live recently at the Boston Jewish Music Festival. ( Full Disclosure: as co-founder of the festival, we brought Schechter here partly because we were excited about this music.) Schechter, known in most circles as the leader of the world-beat band Pharoah’s Daughter, has long plumbed the depths and intricacies of Middle Eastern-tinged music, a welcome change from the klezmer-heavy influence in Jewish music (not that I don’t enjoy klezmer, too).

This CD marks a turning point: a solo effort by Schechter with outstanding back-up by a wide range of musicians that features music based on the Yiddish poetry of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. For those who don’t know, Heschel was an iconic philosopher, theologian, social activist, and mystic who was considered by some critics to be one of the great religious figures of the twentieth century, a rabbi whose impact went well beyond the Jewish world. Born into a well-known, Hassidic family in Poland in 1907, Heschel attended yeshiva in Poland but went on to get a doctorate in philosophy and theology from the University of Berlin. He escaped the Nazis (four family members, including his mother, were killed), first to England and then to the US, where he taught at two Jewish seminaries and wrote a number of poetic and widely read works of religious thought. He marched with Martin Luther King and was an adamant critic of the Vietnam War -— political stances for which he is most often remembered. He died in 1972.

What most Heschel admirers don’t know was that, as young man, Heschel wrote poetry, and in 1933 he published a volume of his verse entitled The Ineffable Name of God: Man. The volume was only translated into English in 2004. The poetry contains the intellectual seeds of the future Heschel —- particularly his grappling with issues of God, man, and existence -— but they also deal with love and nature.

Schechter was given the book and later asked to set some of the verse to music. The result sets 10 of Heschel’s poems to music that blends Eastern European folk song, complex Middle Eastern rhythms and instruments, modern American folk, and even a little rock.

The CD opens with “At Dusk,” a song I simply can’t get out of my head —- a driving, energetic tune with only four short lines as lyrics (“I am a trace of You in the world/ and everything is like a door,/ Let us all trace that trace of You,/ and through all things go to You.) The instrumentation starts off with guitar, violin, cello, and a drum, then adds a soaring flugelhorn solo, mandolin, a trumpet —- even an accordion. Near its end, Shechter’s voice breaks into a chant-like refrain with overdubbed parts, and it’s glorious.

“I and You” opens with a folk-rock guitar that reminded me of Blind Faith’s “Can’t Find My Way Home,” eventually turning into a gently lilting, plaintive, minor-key melody that fits perfectly with the intensely personal suggestions of the text (you’ll need the CD to consult the translations).

The fourth cut, “To A Lady in a Dream,” brings a distinctly different feel that is firmly drenched in the Middle East and love imagery. It begins with Tamer Panarbasi playing a solo on the Arabic kanun, a 26-stringed, plucked instrument, and moves into an intricate rhythm with long melodic lines. The song also features a lovely violin solo from Megan Gold. Bells start “Snow On The Fields,” followed by a simple, haunting, and sumptuously-played arrangement for strings that backs Schechter voice throughout.

“From Your Hands” presents another love poem with dual meaning: “From that gentle bowl—your hand/let me drink rest and comfort–/in the deepest stillness of your voice/let me unravel the mystery–/ ….” Is Heschel talking about a lover or God? That question pops up throughout his poetry; the music captures the ambiguity well.

Tshuvah is a Hebrew word that means “a turning,” or return, and is closely associated in the Jewish religion with the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, when we reflect on our actions and thoughts and seek to return to a path of righteousness, justice, and good deeds —- to turn ourselves around or back. Jews seek forgiveness, personally and communally.

The young Heschel’s poem “Tshuvah” adds another powerful dimension to this somber time of reflection -— it calls God to task as well. It’s another piece of a long, Jewish tradition: the argument with God, holding the Creator to account as well as ourselves. (Another modern musical example can be heard in Leonard Bernstein’s 3rd Symphony, Kaddish, where the narrator rails at God in one of its movements). The ending suggests the nature of the battle: “We, God and man and dogs —/let’s repent together/or each one for the other./ And forgive us our sins/as we forgive You Yours.” It’s a bold assertion.

Schechter’s setting is stark, beginning with ominous, discordant chords plucked on piano strings and echoes; trembling strings enter and a bluesy trumpet (thank you, Frank London) shifts to a driving bluesy riff that repeats and repeats with various accompaniments. It’s reminiscent in a strange way of the lament that accompanies a New Orleans funeral in parts —- but in a distinctly Jewish way. The song ends unresolved. It’s almost perfect —- I only wish Schechter would conjure up an angrier and darker voice.

“My Song” is a Heschel social justice anthem, where he pleads “I want to give to you—world,/The inner lattice of my limbs;/My word, my hands,/the wonder of my eyes,/Take me for service to you,/ and use me for your ends.” Schechter turns it an upbeat and rousing anthem.

A word about the arrangements and musicians. Several of the arrangements are by Israeli-born musicians: three of the arrangements were done by Uri Sharlin, who also plays piano, accordion, and glockenspiel on the CD. Sharlin has played with Anthony and the Johnsons, Natalie Merchant, and was a featured pianist on HBO’s Flight of the Conchords, as well as with Frank London and Pharaoh’s Daughter. One arrangement is by Oded Lev Ari, a graduate of the New England Conservatory, who most recently directed a Billy Holiday tribute concert in New York that featured Madeline Peyroux, Bucky Pizzarelli, and a host of others. He’s collaborated with jazz saxophonist Anat Cohen and the legendary Theodore Bikel. The rest of the arrangements, as Shechter told me, are by the musicians themselves, playing together in studio. All the musicians do wonderful work.

The CD ends with “Youngest Dreams,” the most rocking tune on the set. The Yiddish begins with “I so want to be in love!” and the song just sways with that emotion. There’s even a thrashing, twangy guitar solo.

So pleased you include a sample. Wonderful!