Book Review: La Fontaine’s Beasts Still Know Best

Norman R. Shapiro took on the Herculean task of translating the 17th century French poet’s work—some 240 poems in all—in increments of fifties. He has performed the difficult task with wit and panache.

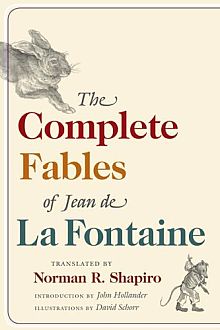

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine (Paperback) Translated from the French by Norman R. Shapiro. University of Illinos Press, 504 pages, $24.

Reviewed by Brigitte Tournier

When Jean de la Fontaine set out in 1668 to “Sow the seeds of virtue…and to amuse” the Sun King, Louis XIV’s six-year-old son, by writing his Fables, he relied heavily on Aesop’s much earlier depictions of animal stereotypes representing human foibles.

In Norman R. Shapiro’s translation of these delightful verses, which pack a mighty moral punch, we once again are reminded that truly nothing has changed that much under the sun in the past 340 years—or ever—for that matter. Whether it be in the stoas of ancient Athens or in the corridors of Versailles, man’s nature is all too predictable and these ever-pertinent fables not only wag a finger of warning but also do so in a totally charming, rhymed manner. The Fables use common animal traits and characteristics, familiar to all but also, at times, plants and some human examples in order to teach their lessons.

Shapiro took on the Herculean task of translating the 17th century French poet’s work—some 240 poems in all—in increments of fifties. He published his first Fifty Fables of La Fontaine in 1988, became somewhat hooked and felt the compunction to publish Fifty More Fables ten years later. This led to Once Again La Fontaine a few years after that and finally to the present volume: The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine, containing the entire works. The volume has earned Shapiro this year’s Lewis Galantière Award, which is bestowed biennially by the American Translators Association for a distinguished book-length literary translation from any language, except German, into English.

Since I have taught some of La Fontaine’s most famous and beloved fables in my French classroom in an independent school in Cambridge, Massachusetts for nigh on twenty years, the lyricism and cadence of the author’s rhymed and metered verse are very familiar and dear to me. It is therefore with great pleasure that I noted Shapiro’s close adherence and faithfulness to these original verses and rhythms and tone—and of course to the all important rhymes—which accompany each fable’s message.

For example in “The Wolf and the Lamb,” in Book I, with its moral that the most powerful of this world will always win every argument, literally, line for line translates the author’s original intent and yet rhymes perfectly in its English incarnation, sacrificing none of the all too familiar chronological punch and dénouement of the story to which the French speaker is so accustomed.

Another particular favorite of mine was the author’s translation of “The Companions of Ulysses” which the by then 71-year-old La Fontaine wrote for the 11-year-old Duc de Bourgogne who was Louis XIV’s grandson and the son of the Grand Dauphin for whom the earlier fables had been written. Shapiro absolutely nails the recounting of Ulysses’ run in with Circe as told in Homer’s Odyssey, when all of his companions have been turned into beasts. As Ulysses pleads with his crew to become “upright man once more” the response is

Should I be less the predator?

You men are worse than wolves with one another,

Stranger to stranger, and brother to brother.

Better a wolf than man malevolent!

I will not change. I am content.”

Rather than being enslaved by their animal instincts, La Fontaine entreats his prince to contemplate the moral of this tale by saying that

Many there are in this world of their kind;

And I would bid you, forasmuch—

Seeing them to their nature base succumb—

Punish them all with your opprobrium.

The clever wit (the best translation of the French word “esprit” I have yet to find) intrinsic in La Fontaine’s work is also beautifully rendered in Shapiro’s translations.

L’esprit was the be all and end all of French society of the time and being nimble of mind and finding humorous repartees was a primary necessity in all courtly interactions. A case in point would be from Book VIII “The Joker and the Fish.” La Fontaine chides those of

Laugh provokers’

Ilk: those who think their silly wit

Transcends all art, though surely it

Falls short! For fools has God created those

Pun-makers, bad ‘bon mot’ magnificos.

Now, in a fable, I shall try to fit

My wit to theirs: we’ll see if I am able.

He then proceeds to tell a fable of a financier’s dinner table at which one jokester is served very small, scrawny fish in comparison with some of the other diners’ helpings. The “comedian” begins by holding the dish to his ear, pretending to listen to what the tiny fish on his plate have to tell him.

I asked if they had any news

About a friend bound for the Indies, whose

Vessel, I fear, might have gone down.

‘We’re much too young to know’ they said

The ruse worked, yet it later backfires because when he got his fish it was

A big one, but so tough,

So old that it could easily have named

Every explorer seeking worlds uncharted

For the last hundred years; those long departed

Souls that the sea’s vast, ancient wastes had claimed!

In his subtle, pun for pun rendering Shapiro serves up this delectable anecdote, including its sobering punch line, as fresh and tasty as the day it was written. Finally, just as finance and economics are so relevant today, they were also a matter of great importance to La Fontaine. One of his most important patrons was Nicolas Fouquet, Louis XIV’s superintendent of finance. La Fontaine tells the tale of “The Cobbler and the Financier,” which in Shapiro’s sprightly translation starts in the following manner

A cobbler used to sing from morn till night.

It was, indeed, a wondrous thing

To watch him, hear him warble with delight,

Happier in his laboring

Than any of the Seven Sages were.

Close by, a neighbor—quite the fine monsieur,

Rich as a king!—sang little, slept still less.

He was, in fact (as you might guess),

The kind we dub a “financier.”

The inevitable happens when the sleep deprived rich man hears that the happy-go-lucky cobbler leads a hand to mouth existence, his livelihood precarious. The financier, wanting to help him with his problem, gives him a hundred crowns. From that day on the situation is reversed and, when the cobbler becomes obsessed with the “cares that fortune brings,” he returns to his neighbor’s door

And, flinging

The hundred crown before him, cries:

“Here! Take them! Just give me back my sleep, my singing!”

Surely it is a sobering lesson for sober times.

When in 1683 Jean de La Fontaine was elected to the Académie Française, mention was made in the speech welcoming him to the illustrious assemblage of les immortels (the immortals as the Academicians are referred to) that this membership would have no other purpose “than the eternity of his name.” Shapiro’s book has certainly contributed to this end by giving the legions of non-francophone readers of La Fontaine the opportunity of a thoroughly satisfying, complete and very rewarding experience of Jean de La Fontaine’s eternal wit and wisdom.

David Schorr’s black and white illustrations add a delightfully whimsical and artistic touch to the beginning of each of the twelve books.

After receiving an Art History degree from George Washington University, Brigitte Tournier moved to Paris, where she remained from 1967 to 1986 during which time she married and had her two children, Emilie and Edouard. She has been teaching French at Buckingham Browne & Nichols school in Cambridge, MA since 1990.

Tagged: Books, Featured, Jean-de-la-Fontaine, Norman-Shapiro

[…] The Complete Works of Jean de la Fontaine, translated by Norman Shapiro. This one’s in keeping with my folklore interests. This review is very favorable, and the excerpts sound really promising. Rimbaud: the Double Life of a Rebel, by Edmund White. I adore Rimbaud. My dad loaned me his copy of Illuminations when I was in high school, and I’ve been carrying it around with me ever since. I know a little about his life — strained childhood, his love affair with Verlaine, his renunciation of poetry and early death in Africa. Rimbaud’s poetry is so strange, so inscrutable, that I don’t really think knowing more about his life would help me to understand the poems themselves, though I might have a better perspective about why he wrote the way he did. Rimbaud is one you give yourself over to, one where you just get lost in the words, where you don’t try to analyze, but only to see as clearly, as vividly, as you possibly can. […]

[…] -The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine, translated from the French by Norman R. Shapiro, on The Arts Fuse -The Hayloft Gang: The Story of the National Barn Dance, edited by Chad Berry, on CMT.com […]