Book Review: Getting Down and Dirty in the Dollhouse: Ibsen and the Kardashians

An underground academic critic explores the fascinating intersections (Hegel and beyond) between the Kardashian sisters’ novel Dollhouse and Ibsen’s play A Doll House. The more things change . . .

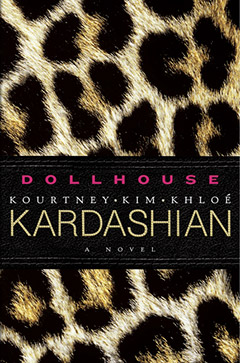

Dollhouse by Kim Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, and Khloe Kardashian. William Morrow, 288 pages, $24.99.

By Hejdë Fraümtraü, Ibsen Scholar

Doubtless the Kardashian sisters (Kourtney, Kim, and Khloe, as listed not alphabetically on the cover page, leading this reader to believe that it is Kourtney who did most to conceive and execute this project, though surely each took an equal share in the actual writing) are familiar with Rolf Fjelde’s claim that the only accurate translation of the title of Henrik Ibsen’s Et Dukherjem is A Doll House. The trio rejects the usual and misleading A Doll’s House, which mistakenly implies that Nora Helmer somehow owns her abode, rather than the other way around. The sisters’ further elision to simply Dollhouse—no article, no space between person and place, a whole world in that one word—is provocative and apt, for their subversive new book shows that the ownership of the house, and of the woman, remains, in the 21st century, an open question.

Dollhouse does its sly, kaleidoscopic work through a series of parallels between Nora in 19-century Norway and Kamille, Kyle, and Kass (note the teasing metafictional connection of these sisters’ names to their authors’) in 21st-century Los Angeles. Nora is constantly occupied with pleasing her husband Torvald and worried about “when I have ceased to be so pretty as I am now.” Kamille opens the novel lamenting that her “arms, legs, and bikini still stung from having been waxed. But it was a good kind of pain,” she convinces herself. The women in this book go to great lengths to meet the prevailing (male) idea of beauty, with waxes and diets and makeup and lavish clothing, not to mention cosmetic surgery. Such measures come at great cost, in more ways than one—but “[j]ust because they were poor now,” Kamille thinks, “didn’t mean they had to be furry and ugly, did it?”

Clearly money—and male control over it—is as much a problem for the sisters as it was for Nora. When their wealthy father dies and his fortune disappears, they learn “that money was power, and that no money meant no power.” Desperate to help Torvald, Nora forges her father’s signature on a loan and takes in “needlework, crochet-work, embroidery, that sort of thing.” Kamille becomes a supermodel—the ultimate object/subject of the heteronormative, asymmetric power structure. Kamille obviously has more “rights” than Nora; she gets to cash her own checks and open her own mail.

But Dollhouse troubles any unthinking narrative of Progress in Women’s Rights. One critic has noted that the silk stocking scene, in which Nora allows Dr. Rank to touch her flesh-colored stocking, “shows the sexual side of the Helmer mésalliance.” But at least Nora gets to keep control of her undergarments. Kamille’s ex-boyfriend “was secretly hooking up with Sarah what’s-her-name for three months before Kamille found out, even though everyone tried to tell her, and even though she’d come across a slutty black lace thong in his locker. Jeremy [the boyfriend] claimed that the thong was a Valentine’s Day present for her, which was beyond lame, since it was so obviously used. She’d had similar experiences with other boyfriends.” These multiple mésalliances point to the myriad ways modern life continues to objectify women, the way men continue to treat them as dolls (a term that appears fully 19 times in Dollhouse: “put this on, doll”; “she was wearing nothing but a red baby-doll nightie”; “Hi doll!”; “DOLL, WHERE R U”; and so on).

The Ibsen-Kardashian intertextuality inheres at the most minute semantic level, as well. Kamille’s friend Simone’s promiscuity leads Kass to say, “That girl is such a slore”—a clear reference to the Norwegian slør, which means veil. Synechdochically, this suggests someone who conceals herself, especially from the male gaze, or something threatening that must be contained, constrained, indeed quarantined—a reading confirmed by the rest of Kass’s sentence: “honestly, she’s like one giant yeast infection.” Something called The Urban Dictionary sources “slore” in a combination of “slut” and “whore” and notes that the word is used “[u]sually in terms of a real trick ass bitch, who can’t keep dick out her mouth/puss/rectum.” Which brings us back to Ibsen and Nora’s realization that she has “existed merely to perform tricks for . . . Torvald.” Scholars better steeped in the Scandinavian languages will be able to mine the rich veins of other Kardashian neologisms: the possible connection between celebuspawn and silingsbøtter (milk bucket) is suggestive; and I will be interested to see how obscure terms such as mani-pedi, perv, v-card, and va-jay-jay are illuminated by knowledge of Old Norse.

Sometimes the sisters seem to take their critique of the commodifying effects of contemporary, celebrity consumer culture too far. “Voyeur” is a clever name for a nightclub in an age of spectacle, and an onlooker’s assertion that she is “totally tweeting” about Kamille neatly updates Torvald’s constant worries about what panoptic society will say. But the idea that Kamille could sell rights to televise her wedding is absurd, even in 2012. Still, such overstepping is part of the subversive satire. Was it for this, the Kardashians seem to be asking, for botox and bikinis and labioplasty and xanax and appletinis, that Nora slammed the door on Torvald over a century ago?

The Kardashians’ most stinging indictment of the patriarchy, and most disquieting admission of its enduring power, is in the seemingly happy conclusion of the novel. The story centers around a night when Kamille’s boyfriend Chase—a name redolent of the predatorial male, a baseball star wielding phallic bat—has intercourse with a drunken Kass. (Whether this coitus was consensual or not remains a provocative mystery—one that problematizes the very term “consensual,” belying as it does the power imbalances that are always and already inhering in sexual relations.) Chase is eventually found out, and the TV wedding is called off. If Nora’s decision to leave her children is “a rejection,” as one critic incisively puts it, “of Hegel’s theory of women’s role in the family and society,” then Kass’s decision to keep the baby Chase fathered in her is equally anti-Hegelian. Kass dreams about having a girl and picks out her name, but Annabella (anna=Gracious; belle=beautiful) is not to be. Instead the book ends with the birth of Alexander (alexo=defender; andros=of men). Alexander, pupil of the misogynist Aristotle (“a female is but a deformed male”), commander, emperor, conqueror, straddling Mother Earth and penetrating Her with his spear.

It is hard to imagine a more fitting name for the patriarchal vessel, or a more chilling way to end this novel, than with the new aunt, Kamille, singing to this “adorable” little monster, a lullaby soundtrack to a haunting last line: “Everything was back to normal again.”

Hejdë Fraümtraü is the pen name of Chris Walsh, who is not an Ibsen Scholar.

Tagged: A Doll's House, and Khloe Kardashian, DollHouse, Henrik Ibsen, Kardashian sisters, Kardashians, Kim

Hejde, Hejde, Hejde HO! Great stuff. Do not hide behind this Chris Walsh pen name ruse. You rock, Hejde. Own your awesome power.

A fascinating study, meta in every sense of the word. I only wonder about the personae of these clearly pseudonymous KKK sisters. Hejde, come clean. You invented them, didn’t you?