Theater Review: Of Race and Real Estate — Clybourne Park

Given his full-throttle depiction of the myopia of middle class mores, Bruce Norris is more in the flamboyant satiric line of Sinclair Lewis, who also trained his sharp ear and eye on the Midwest, the American heartland, jabbing away at American delusions of community, status, and self-satisfaction.

Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris. Directed by Brian Mertes. Presented by the Trinity Repertory Company, 201 Washington Street, Providence, Rhode Island, through November 20.

By Bill Marx

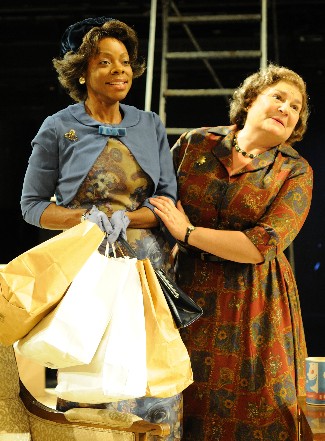

Mia Ellis (Francine) Anne Scurria (Bev) in the Trinity Rep production of CLYBOURNE PARK. Photo: Mark Turek.

My fear was that Bruce Norris’s Clybourne Park, hailed for its spiky and sparky comic view of the clash between American racial relations and property rights, could not possibly be as jolting and provocative as the mainstream hosannas would have it. The well-acted, generally rousing Trinity Repertory Company production suggests that Norris’ script is cutting as far as it goes—which is about as far as a sharply rendered lampoon of the American dream can.

No doubt one reason the play won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, 2011 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Play, and the 2010 London Critics Circle Award for Best Play was that the time-tripping sass of its central concept is wedded to an reassuringly conservative idea—when it comes to issues of race and property, Norris suggests, the more things change, the more they remain the same. The message is not very deep, but there’s an enormous amount of painful laughter to be had from puncturing delusions to the contrary, especially if you prick blindness with pinpoint accuracy.

Clybourne Park mischievously and pointedly slices and dices polite notions of community, understanding, and friendliness (all bets are off when property values are at stake) but weakens when it overreaches in its attempt to get at the core of American unhappiness. It turns out that we can’t be good neighbors because of our mutual isolation—no amount of anger or empathy can smash down the walls between us.

In other words, Norris is not, as Artistic Director Curt Columbus puts in his program notes for the Trinity Rep production of Clybourne Park, “in the tradition of Ibsen and Chekhov.” He is more about exposing the embarrassment generated by our hypocrisies than digging underneath them. Given Norris’s full-throttle depiction of the myopia of middle class mores, he’s more in the flamboyant satiric line of Sinclair Lewis, who also trained his sharp ear and eye on the Midwest, the American heartland, jabbing away at American delusions of community, status, and self-satisfaction.

No wonder Norris is charged by some with cynicism—like Lewis, his job is to use humor to show the ugliness and selfishness percolating underneath our pieties, not only about race and real estate but marriage as well. He’s at his best when he makes us squirm as well as laugh at the pettiness in ourselves, less effective when he resorts to kicking around cartoons for easy chuckles.

Anne Scurria (Bev) and Timothy Crowe (Russ) in the Trinity Rep production of CLYBOURNE PARK. Photo: Mark Turek

Clybourne Park’s first act, set in 1959, bows to the plot line of A Raisin in the Sun. A middle-aged couple, Russ and Bev, unknowingly sells its desirable two-bedroom (at a bargain price) in a predominately white community to a black family, causing consternation among their neighbors. Act two takes place 50 years later, where the same home, recently bought by a young, white couple, is set to be razed to the ground and replaced by a grander manse, causing fear among the majority black residents that history-obliterating gentrification is on its way. The warring parties have come to make peace, but war results.

Each act takes on the dramaturgical colorings of the era. Act one is a “well-made” play revolving around why Russ has become so morose and hostile. Bev is worried and asks a priest to come by as the couple prepares to move, but his attempts at drawing Russ out are rebuffed with insults and obscenities, followed by the arrival of Karl and his pregnant and deaf wife Betsy, who confess that they tried to offer money to the black family to change their mind about moving into the home but were rebuffed.

Russ and Bev know nothing about the sale of their home to blacks, but the bitter confrontation, especially between the Karl and Russ, makes the reasons for the latter’s hatred of the community, rooted in its treatment of his son after he returned from Korea, clear. His curse on the community takes a territorial turn: the footlocker of the couple’s son is buried in the back yard for the new owners to stumble upon 50 years later. Meanwhile, the maid Francine and her husband walk out of the home, declaring that the whole white crowd is crazy.

Norris is on spot-on in his evocation of the language of casual racism (the exchange about whether blacks can ski is priceless), though sometimes the dramatist has a tendency to serve up smug caricatures, such as the ever-smiling Betsy and the ineffectual priest Jim, who admits he is wearing a truss. At the center of the Trinity Rep production are two marvelous performances, Timothy Crowe’s volcanic Russ, an immaculately timed portrait of a man fighting but failing to tap down his inchoate anger, and Anne Scurria’s Bev, an uptight but big-hearted homemaker struggling to achieve some sort of normality. She articulates the play’s only words of unity: “If someday we could all sit together, at one big table and, and, and, and … (trails into a whisper, shakes her head). Clybourne Park goes no further than that “and”.

Rachel Warren (Lindsay) and Mauro Hantman (Steve) — the insensitive joke must be told in the Trinity Rep production of CLYBOURNE PARK. Photo: Mark Turek.

The second act tends towards the flyblown, structurally, though the cast members from act one return to play new roles, setting up some interesting thematic parallels. Two representatives of the black community, Lena and Kevin, come by to negotiate with a white couple, Lindsay and Steve, about objections that the latter are gentrifying the neighborhood by building what sounds like a “McMansion.” Lawyers are present, of course, and the conversation, after interruptions and proclamations of friendliness, turns ugly, if uproarious, when Steve raises the issue of race. The play explodes into a contest of politically incorrect jokes.

The stand-up mayhem is a hoot and put over with panache by the cast, especially Mauro Hantman as the befuddled “truth-teller” Steve and Rachael Warren’s Lindsay, who is a monument to liberal shrillness. As Lena, Mia Ellis provides the right note of dignified disdain, and Joe Wilson, Jr.’s Kevin combines good nature with flickers of aggression. Yet once the lesson of mutually assured destruction is over, there isn’t much left but the earnest irony that the entire imbroglio was over nothing: the real conflict is most likely a matter of taste rather than a battle over land, race, and history. Aware of this let-down, Norris adds a coda that supplies a domestic image of isolation and death that tries, but doesn’t succeed, to raise catharsis-via-insult into revelation.

Director Brian Mertes handles the performances with skill, though I wish he (and some of the performers) had done more to work against the superficiality of some of the script’s characterizations, and whenever he adds something to the script, the move feels wrong—for example, having Russ turn on the radio at the end of the act to hear Ray Charles’s 1972 rendition of “America the Beautiful” hits a sour note. But there are few of those in this highly entertaining production of Clybourne Park, an amusingly acidic primer on the real values at the heart of American real estate.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.