Book Review: Film Critic Manny Farber — Ravenous Genius

Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber. Edited by Robert Polito. Library of America, 1000 pages, $40.

Reviewed by Justin Marble

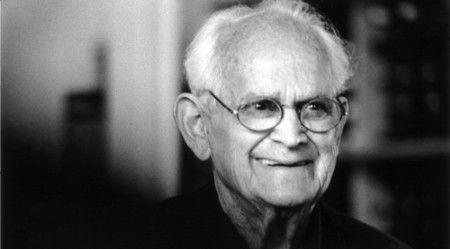

Manny Farber (1917-2008): One of the unruly giants of 20th century film criticism.

Film critic Manny Farber’s landmark 1962 essay “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” champions the underground, manic, frenzied, messy “termite” films against the by-the-book, consciously significant, pompous and often critically-adored “white elephant art” of the mainstream. He claims, in his antically colorful way, that “termite-tapeworm-fungus-moss art … goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.” Like the marginalized films he loved, Farber’s own writing is a form of “termite art.”

Farber dives into each film he reviews, whether he “likes” it, or not, and bites his way into its heart at breakneck speed, leaving a trail of dizzying vocabulary and provocative observation until the reader is left with his mind reeling. What’s more, there’s little left to gnaw on– since Farber has already chewed everything up himself.

Spanning from the early 1940s to the late 1970s, “Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber” tackles the golden age of cinema from an alternative but wholly engaging perspective. At times contrarian to a fault, with a “who’s that?” pantheon of filmmakers like Val Lewton and Raoul Walsh, Farber took the word “critic” seriously, unafraid to detail just what he thought was wrong with the latest Truffaut or DeSica film everybody else was raving about.

This non-conformity can be infuriating – I wanted to reach through the page and strangle him for attacking Bergman’s “Wild Strawberries” – but his writing irritates not because it is poorly thought out, but because it is so nuanced, so observant, so richly detailed in the tiniest moments. In the “Strawberries” essay, among others, one gets the feeling that Farber could miss the point of a film completely, because he can spend too much time on how the film was photographed, or how an actor delivered a certain line, rather than what the film is ultimately about. But it’s easy to forgive him simply because his dedication, passion, and attention to detail are extremely rare, if not discouragingly unique.

In fact, Farber would argue that these tiny moments are what’s important about film, and by extension, about criticism. In a time of decadence, when movie reviews have been poisoned by the Siskel-and-Ebert “thumbs up/thumbs down” or Metacritic mentality, the latter boiling down complex opinions into a numerical value, Farber’s writing reminds us of the limitations of naked judgment. In some reviews the reader never even gets the sense of whether Farber thought the film was any good or not, because he spends the review analyzing one thing — a set, a line, an actor — that he found particularly interesting.

In fact, Farber would argue that these tiny moments are what’s important about film, and by extension, about criticism. In a time of decadence, when movie reviews have been poisoned by the Siskel-and-Ebert “thumbs up/thumbs down” or Metacritic mentality, the latter boiling down complex opinions into a numerical value, Farber’s writing reminds us of the limitations of naked judgment. In some reviews the reader never even gets the sense of whether Farber thought the film was any good or not, because he spends the review analyzing one thing — a set, a line, an actor — that he found particularly interesting.

In some ways this approach is more powerful, or at the very least as rewarding, than a verdict. Farber’s reviews would never show up on a movie trailer, he would never exclaim “Go see The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance!” Instead he will analyze the way John Wayne walks, the way he sits back in his chair, and in doing so will tempt you to pop in the DVD to see what he’s talking about. Farber’s role is more of an intellectual swashbuckler than neat-cornered consumer guide.

Be warned: there is a density to Farber’s writing that might prove formidable to those weaned on fluffy, airy, modern newspaper-based film criticism. He tends to use a ten-dollar word when a two-cent one would do. Sometimes the wheels come off his sentences and he crashes into a corner: the piece ends with nothing arrived at, just perceptions arranged in a web-like fashion. But it’s part of his indispensably eccentric process, the price that comes with approaching each film in his own frenzied way.

As a young critic, one of the sublime virtues of “Farber on Film” is the opportunity to read an insightful critic exclaiming and arguing through the decades of cinema when the masters were at work. Essays on Godard, Truffaut, Bergman, Capra, Wilder, Fassbinder, Kurosawa, and others provide a cinematically thrilling time capsule. It’s particularly refreshing to read penetrating criticism of artists widely talked about as nigh-bulletproof in the present day. And reading Farber at the end of his career delving deep into Werner Herzog, who was just beginning his, offers a paradoxical vision of craft, the meeting of two ornery masters, one winding down, the other starting up.

Farber On Werner Herzog

The overwhelming isolation of every moral in the human kingdom is the sensation of any Herzog frame. When two types of loss-alienation can be split apart within one frame, the movie inevitably is at its most hurtful and associative. Perhaps his entire oeuvre defines itself around the miracle scene, utterly dirty, of a wiry Algerian hammering stones into gravel. His clenched doggedness is suddenly matched by an equally weathered intruder who takes a stiff, belligerent stand toward the camera. It catches a whole area’s existence, dry, mid-Sahara, and the outsider’s impotent relation to it. Over this image is a rasping incantation: The gates of paradise are open to everybody … there works are inspected which no one would do … you slake lime and are chosen by this for the rich.”

Herzog is one tough guy with an ability to be pliant, gentle.

Werner Herzog, 1975

Beyond that, and in some ways more crucial, Farber challenges today’s critics to be more than idle, passive observers, anemic blurbers and box office followers, but to attack, engage, and shape the culture’s conception of film. It’s not about agreeing with Farber – sometimes he doesn’t even seem to agree with himself – but to absorb his desire that the reviewer should fight for a recognition of movie art, no matter where it might be.

In a way, Farber was both termite and an (unwhite) elephant: a termite in the sense that he chomped on every film he saw, ripping through it with abandon, and an elephant in that his massive and significant contribution to criticism cannot be ignored, or forgotten.

Tagged: Farber on Film, Justin Marble, Library-of-America, Manny Farber