Visuals Arts: Rembrandt and I in Oman

It cannot be said that the average Omani was waiting for an exhibition of Rembrandt etchings.

By Gary Schwartz

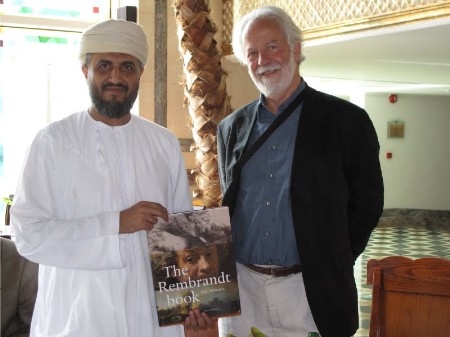

Gary Schwartz spreading the word about Rembrandt to Abdulrahman al-Salimi, director of the al-Salimi Library in Oman.

“Frankincense from Oman and paintings by Rembrandt were both part of the good life in the 17th century.” That unlikely quotation is from the script of a film that I wrote and presented this summer to accompany an event that linked Oman and Rembrandt. The event was an exhibition of 100 Rembrandt etchings from the Rembrandt House in Amsterdam (79 prints) and the Rumbler collection in Munich (21 prints), supplemented by three of the copper plates from which etchings were printed. The exhibition was held in the Afrah Ballroom of the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Muscat, which was subjected to a major remake for the occasion.

It cannot be said that the average Omani was waiting for an exhibition of Rembrandt etchings. Based on my own man-in-the-taxicab research, his name was unknown to the locals until the exhibition publicity got under way. As I understand it, the initiative came from the top of Omani society. The Omani Minister of Religious Affairs and Endowments, Abdullah al-Salimi, and his remarkable nephew Abdulrahman al-Salimi, director of the al-Salimi Library (the name is sometimes spelled al-Salmi), were seized with the ambition when they visited the Rembrandt House in Amsterdam a few years ago.

From then to 19 August 2009, when the exhibition opened, plans advanced and receded along the usual bumpy road of such projects, with a few unusual bumps thrown in. In terms of content, the only restriction requested by the hosts was that no nudes be shown. Considering the circumstances, the Rembrandt House did not consider this an unacceptable form of censorship. There are enough places in the Western world where politicians interfere with the arts in the name of decency and where museum directors accept or anticipate their dictates.

A much larger bump was climate control. The paper on which etchings are printed is sensitive to changes in relative humidity. Quick, sharp changes can cause paper to curl or buckle. The climate situation in a dry, air-conditioned ballroom separated by a few automatic glass doors from the super-humid subtropical heat of Muscat in August is not a model of stability. The adjunct director of the Rembrandt House, Michiel Kersten, engaged in a heroic campaign to get the humidity in the ballroom under control. Around the time of the opening, this involved flying in a battery of humidity machines and monitoring their effect day and night. Kersten did not accept expressions of commiseration for doing this job. “This is great work,” he said. “This is what it’s all about.”

My own contribution was in the educational show-biz realm. At the beginning of the summer, the Rembrandt House and the Netherlands embassy in Muscat decided that Rembrandt needed more of an introduction in Oman than the summary text panels of the exhibition. They asked me to write and star in a 10-minute film (it ended up lasting 15 minutes, but no one seemed to mind) on Rembrandt in Amsterdam, with as many references to Oman as could reasonably be included.

As I confidently expected all along, the commission was extended to include an invitation to Muscat for the opening and to stay on to guide guests of the embassy around the exhibition. And so I spent a week in the Grand Hyatt with my wife, doing our bit for the project, enjoying the hospitality of the Dutch ambassador and the al-Salimis, and soaking up impressions of this first-time visit to the Arabian Peninsula.

The culture shock was considerably softened by the luxurious accommodations and by being driven around in comfortable Toyota SUVs on brand-new roads to top touristic destinations and nice lunches and dinners. Halfway during the week, Ramadan began, allowing us to participate in elaborate sunset iftar buffets while sneaking sandwiches and water in the daytime. For a travelogue, see here.

One thing I was especially looking forward to were the reactions to Rembrandt’s art on the part of Muslim visitors to the exhibition. Few of their remarks, though, concerned religion. The first thing that seemed to concern them was the size of the etchings. They found it difficult to believe that an important artist would bother making such small works. The impression of smallness was brought about partly by the presentation. The large space was not broken by partitions, so on first view the prints looked a lot smaller than they would had the visitor been brought up close to them to begin with.

A visitor inspecting the cover image for the show, Rembrandt's self-portrait as an Oriental ruler.

Newspaper stories on the exhibition, many of them illustrated with big color reproductions of Rembrandt’s most famous paintings, put beginners on a wrong foot. It turned out moreover that there was no word in Arabic for etching; the word that was chosen to describe the displays was not always distinguishable from picture.

Another question I had to answer again and again was how a print could be an original. The audience wanted to know, as would members of the European public attending a print exhibition for the first time, how many impressions had been made of each plate and whether or not they were printed by the master. My carefully nuanced answers could not have satisfied the questioners very much.

One visitor did bring up a religious issue. He wanted to know whether in his depictions of patriarchs like Abraham Rembrandt might have consulted Islamic holy books. This would have far-reaching consequences for the iconography of his works. For one thing, the son of Abraham taken off to be sacrificed would be not Isaac but Ishmael. Although there is no evidence for this in Western art, I could not say flatly that it was impossible. However, neither that man nor any other of the people I guided was upset by the Christian message in Rembrandt’s works. (Some writers of letters to the editor of Omani newspapers were.)

The most surprising comment on the exhibition came from Minister Abdullah himself. At a lunch on his farm outside Muscat to which he invited all the foreign visitors involved in the project, I presented him with a copy of my book of 2006 on Rembrandt. He accepted it graciously (and later reciprocated with the gift of a decorated dagger, a khanjar of the kind every Omani gentleman must have) and said the following, as I understood it and recall it a few months on: “Until about 200 years ago, we had problems with paintings. They were not always permitted. But we have fewer problems with prints. Paintings are direct images, often of living people. Prints are not direct.”

This is a distinction that I do not know from studies of the reception of art in the West. When we speak of images we do not make a categorical distinction by technique or between unique works and multiples. Yet this is not a trivial matter. Inquiries back home into the Muslim theology of images have not yet brought enlightenment. Once more my life has been enriched with a fascinating and unfathomable question.

———————————————————

Am still ensconced in the oak groves of Wassenaar at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study of the Humanities and Social Sciences. I am the one with the beard. There too I am working on the reception on the Persian Gulf of Netherlandish art, not today but in the 16th and 17th centuries. For the moment I will not be traveling anywhere except up and back from Wassenaar to home on the weekends and in between time for flu shots and dental appointments. Although having said that I must admit that Loekie and I have just accepted an invitation to the opening of an exhibition of the work of the phenomenal Charlotte Mutsaers in Oostende in two weeks.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor and publisher; teacher, lecturer and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book (2006). His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, appeared every other week from September 1996 to April 2007 and has been appearing since then irregularly. His most recent book on Rembrandt is one of the six titles nominated for the Banister Fletcher Award for the most deserving book on art or architecture of that year.

© Gary Schwartz 2009.

Reactions to Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl.

Tagged: Amsterdam, Gary-Schwartz, Muscat, Oman, Rembrandt, Rembrandt House