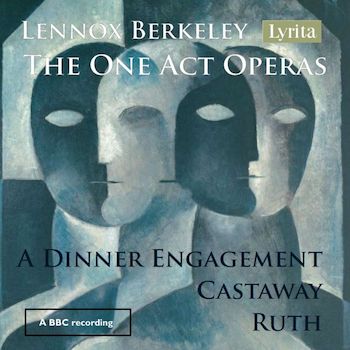

Classical Album Review: Short Can Be Good — Three Splendidly Varied One-Act Operas by Lennox Berkeley

By Ralph P. Locke

I was pleased to encounter all three compact operas. Lennox Berkeley seems to me more and more an admirable, indeed lovable, composer, and a bit of a chameleon. I like him in all his various colors.

Patricia Clark (soprano), Alfreda Hodgson (mezzo), Peter Pears (tenor), Thomas Hemsley (baritone), and others.

BBC Northern Singers, BBC Northern Orchestra; English Opera Choral Group Chorus, English Chamber Orchestra, conducted by, respectively, Maurice Handford, Steuart Bedford, Meredith Davies

Lyrita REAM2144 [3 CDs] 190 minutes

To purchase, click here.

Short operas (as comedian Rodney Dangerfield might have put it) don’t get no respect. Opera lovers have been trained to want things to be grand, complicated, and rather long. But the truth is that there are hundreds of short operas that make their point in less than an hour. And the best leave an audience feeling that they have had a delightful or powerful (or whatever) experience. Five — Pagliacci, Cavalleria rusticana, and the three that make up Puccini’s Il triticco — are part of the standard “canon.” A somewhat larger number — works by Mozart, Ravel, Stravinsky, Hindemith, Weill, Viktor Ullmann, Menotti, Poulenc, Britten, Barber, or Bernstein, say — receive performances by college opera studios and local opera companies –and very occasionally by big companies (sometimes in halls that are too big for the work to make its full effect). And dozens, perhaps hundreds, of others await wider discovery, even though they were composed by composers much loved and admired for other works: Handel, Rameau, Gluck, Bizet, Saint-Saëns, Reynaldo Hahn (in three very short acts), Granados, Zemlinsky. A special plus for short operas: one can put two or three of them together to make a splendidly varied evening’s entertainment.

I was delighted to receive a three-CD set containing the three one-act operas by Lennox Berkeley (1903-89), one of England’s most accomplished composers in the mid to late 20th century. Not that long ago I raved, here at Arts Fuse, about the belated release of a BBC studio recording of Lennox Berkeley’s 1954 full-length opera, Nelson. That work treats, often powerfully, the extramarital relationship of Admiral Horatio Nelson and Lady Emma Hamilton. The new release, too, derives from BBC broadcasts, as preserved on excellent equipment at home by Richard Itter and now approved by the BBC and the musicians’ union for commercial release.

Each of the three one-acters creates its own world, very effectively, as one might expect from a composer who, after training at Oxford and under Nadia Boulanger, had gone on to write fine scores, not least for the film industry. A Dinner Engagement and Castaway have well-shaped librettos by Paul Dehn; Ruth has a capable one by Eric Crozier, who was co-founder of the English Opera Group and the Aldeburgh Festival and librettist for Britten’s comic opera Albert Herring.

A Dinner Engagement (1954) portrays the attempts of a near-penniless aristocratic Lord and Lady Dunmow to prepare a dinner intended to welcome a duchess and her “glamorous bachelor son” Philippe. They have bought their daughter Susan a new dress and special lipstick in hope of making her appealing to Philippe. The couple, and a maid whom they have hired for the night, prepare the duchess’s national dish, but the oven starts to smoke. Susan puts her dress on wrong and overapplies the intense lipstick.

There is a satirical march as the duchess and her son enter, surprised to find that they are being entertained in … the kitchen. (This modest house apparently has no dining room.) Fortunately, the duchess has brought some paté de foie gras, which will have to suffice for dinner. The prince explores the pantry and has a debate with Susan over the recipe for pickled walnuts, in the course of which the two fall in love. He sings her a love song in French.

Composer Lennox Berkeley at the piano.

The opera ends when the duchess agrees to pay the lord and lady’s overdue bill from the grocer and welcomes Susan as bride to her son. The young(ish) couple repeat the French song while the others comment with delight — the duchess saying that Susan will “make my son a happy father [and] make our court a little gay.” Susan quietly admits that she was a fool to think that she could not possibly love a prince. Curtain.

The libretto was clearly intended for an audience of culture vultures (people like me) because it makes passing allusions to famous lines from Shakespeare’s Hamlet and (in French) Corneille’s tragedy Le Cid as well as to the tune of Puccini’s “O mio babbino caro” (from Gianni Schicchi, from the aforementioned Il trittico). The music is mostly tonal in the manner of, say, Poulenc. It is rather motoric and tinged with sarcasm, like whole sections of Britten’s Albert Herring or Stravinsky’s Rake’s Progress. But it becomes lyrical during the scenes with Susan and Prince Philippe. The work requires a chamber orchestra (as do the other two operas), and it includes an active piano part. It has been performed widely, no doubt because it is at once so attractive, humorous, and conversational — requiring of the singers clarity of diction almost more than beauty of tone production.

Ruth (1955-56) is a very respectful and affectionate retelling of the brief but stirring biblical book of Ruth, whose main characters are the childless young widow Ruth, her mother-in-law Naomi, and Boaz, the kinsman who agrees to marry her, thus ensuring her well-being and the continuation of Naomi’s family line.

The music has a stately dignity, presenting all the characters as noble and well-intentioned. The libretto incorporates numerous chunks of the Book of Ruth, of course, but also bits from elsewhere. (I noticed parts of Psalms 23, 31, and 47 — “O clap your hands, all ye peoples.”) Naomi and Boaz, at least in this performance, come off as more articulate and moving than Ruth herself. Perhaps some other soprano could make more of Ruth’s famous speech, directly from the Bible: “Entreat me not to leave thee…” The libretto adds to the biblical texts some vivid and newly written passages, giving Berkeley an opportunity to create effective choruses for the Moabite Women and the (male) Reapers.

Castaway (1966) is based on the episode from Homer’s Odyssey in which Odysseus is shipwrecked, reaches shore, and falls in love with the princess Nausicaa. A blind minstrel, not knowing who this stranger is, sings of Odysseus’s exploits and of the faithful Penelope, who waits for her beloved husband to return. Odysseus determines to head home, and Nausicaa wishes him well: “O! never say that I loved you to her whom you love more.” The work kicks up quite a bit of excitement, not least during the minstrel’s extended account — with spirited reactions from the chorus — of the Greeks’ ruse: entering Troy in the belly of a giant wooden horse.

The performances of all three works are generally solid and communicative, though I found the words hard to catch without looking at the printed texts. In the header, I have listed the most famous of the singers. Patricia Clark, Belinda in the long-admired Janet Baker/Anthony Lewis recording of Dido and Aeneas, is touching and eloquent here as Nausicaa in Castaway. Several lesser-knowns contribute equally splendid work, including, in Castaway, Geoffrey Chard as Odysseus, and Kenneth MacDonald as the Blind Minstrel.

Engagement and Ruth are studio recordings, broadcast in 1966 and 1968, respectively. Castaway is a performance from the 1967 Aldeburgh Festival. The sound on all three is good mono. I suspect that it has been “monitored” for radio purposes because nothing is ever very soft or very loud. The most vivid of the three performances is Castaway, perhaps in part because it was made at a staged(?) performance. We hear the audience laugh at one unintentionally amusing line: Odysseus, naked on the shore, wonders if the maidens whom he observes from afar as they sing are “some brutal tribe of barbarians, practicing their fertility dances.”

Castaway is a recorded premiere. The other two works can be had in more recent performances on Chandos. Those recordings are in stereo, which always helps when several people are singing at once. Opera authority Charles Parsons, in American Record Guide, hailed the two Chandos releases. He found Dinner Engagement “a total delight” but thought Ruth rather too oratorio-like and “statuesque” a work (November/December 2004; September/October 2005).

I was pleased to encounter all three operas. Berkeley seems to me more and more an admirable, indeed lovable, composer, and a bit of a chameleon. I like him in all his various colors.

Informative but inelegantly written booklet-essay. Clear printed librettos. The recordings are not divided into enough tracks: there should be an easy way to jump to Ruth’s aforementioned big plea to Naomi.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

[…] Recordings Classical Album Review: Short Can Be Good — Three Splendidly Varied One-Act Operas by Lennox Berkeley Artfuse.org […]