Book Review: The Préversities of Jacques Prévert — Enthusiastically Translated

Norman Shapiro’s enthusiasm as a translator is felt not only in the versions themselves but also in his introduction and notes. He relishes finding equivalents for Jacques Prévert’s rhyming, which induces him to take some justifiable liberties in regard to the original. The volume is a true labor of love.

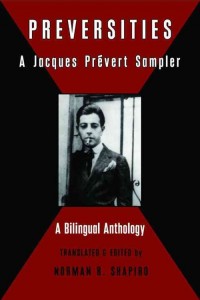

Préversities: A Jacques Prévert Sampler by Jacques Prévert. Translated and edited by Norman R. Shapiro. Black Widow Press, 469 pp., $24.

By John Taylor

The back cover résumé of Norman R. Shapiro’s skillful and oft befittingly witty translation of verse by Jacques Prévert (1900–1977) reports that the volume Paroles sold some 500,000 copies when it appeared in 1945 and that Prévert’s “poems are taught widely in France and included in all major anthologies of 20th-century French poetry.” Actually, it seems that the various subsequent editions of Paroles have sold a total 2.5 million copies, a sum implying that the author of the lines “Our father who art in heaven / Stay put / And we’ll stay here on earth” stands not far behind Albert Camus (1913–1960), the author ofThe Stranger (1942), in the list of modern authors who wrote durable bestsellers.

Taught widely? Indeed. My French-American son (born in 1992) was given Prévert to read during his last two years of grade school, though not afterwards, when his middle-school French classes focused on Molière. And a quick survey, taken among my French poet-friends in their forties and fifties, confirmed that they too had studied quite a lot of Prévert at about the same tender age. For example, they had worked through and even been asked to imitate the well-known “How to Paint the Portrait of a Bird,” which begins predictably enough (“First paint a cage / with an open door. . .”) but then ends with a touching twist:

If the bird doesn’t sing

that will be a bad sign

a sign that the portrait is bad

but if it sings it’s a good sign

a sign that you may sign it

so gently as you can you pluck

one of the bird’s feathers

and you sign your name in a corner of the canvas.

Why did these same poet-friends systematically retort “Ah bon?” when I mentioned that I was going to review a volume of Prévert translations? In other words, an incredulous “Oh really?” indicating that Prévert is not included among the essential poetic influences flowing into the twentieth century from Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine, and Mallarmé and picking up along the way some of the Surrealists (with whom Prévert consorted for a while, roughly between 1925 and 1930), ex-Surrealists, and somewhat-Surrealists, Pierre Reverdy (1889–1960), Henri Michaux (1899–1984), René Char (1907–1988), and the equally playful yet more profound Robert Desnos (1900–1945), among them. Does the poet of “The Starfish” fit in to that company?

The starfish

when you throw it back

like little Opéra twinkle-toes

dances a bit

disappears and so it goes

Always one head

two arms two legs

That’s it.

Of course, for American readers, these lines recall William Carlos Williams’s poetics of objects (cf. “The Red Wheelbarrow”) but also those of Carl Sandburg (“The fog comes / on little cat feet. . .”). From the standpoint of popularity and educational usage alone (at least during the 1950s and 1960s, when I was attending American schools), the latter poet probably provides the most useful analogy to Prévert. En passant, let me cite this additional Williams-Sandburg-like quatrain:

Standing

The wind

Sits a while

On the rooftop tile.

Yet doesn’t such verse lack the intense, but also ironic, seriousness of the poems, prose poems, and proems of Francis Ponge (1899–1988), the contemporary whose experiments with writing about things were so much more decisive for subsequent French poets?

Other clues to contemporary French poets’ indifference to Prévert, to their placing him at best on a school library shelf, or to their stuffy aloofness (as you will say if you are already a Prévert fan, and Shapiro’s versions muster what’s necessary, in English, to make you one) lie in the very title of his best-known book. The polysemous “paroles” can mean “song lyrics.” Prévert wrote some, notably for the famous “Les Feuilles mortes” sung by Yves Montand, but Rimbaud and Mallarmé had already long cleaved out a difference (and hence a trench) between “poem” and “song.” Snobbishness is less involved in this distinction than suspicion about the validity of what most songs demand prosodically (meter, rhyme, repetition, refrain) and especially semantically: clear simple imagery, whereas the world, the psyche, nature, human existence, and so on, are almost always considered to be muddled and murky by modern and contemporary poets, who try to reflect the depths of the confusion or the intricacy.

More generally, the title Paroles underscores the poet’s confidence in “speech,” in “words”—Prévert’s emphasis on colloquial speech is not really the issue here. Several major poets from the next generation turned against such a faith. Writing in Saccades (Fits and Starts), a sequence included in Gravir (To Climb, 1963), Jacques Dupin qualifies his own style as a “parole déchiquetée”; that is, poetic discourse that is “shredded,” “torn to pieces.” The challenge that Dupin puts to himself is that of renouncing and even denouncing smooth, simplistic rhetoric, a duty that also recalls Philippe Jaccottet’s notion of “not cheating” with words (which can trick us into believing in ideals and chimeras) or Yves Bonnefoy’s caveat that poetic beauty “ruins being” and that it must consequently be “tortured, broken on the wheel, / Dishonored, found guilty, made into blood / And cry, and night”—as he puts it, via Anthony Rudolf’s version, in Yesterday’s Wilderness Kingdom (1958).

André du Bouchet (1924–2001) broke up his poems all over the page because the pertinence of traditional syntax and logical connectors, vis-à-vis our perceptions and mental processes, also needed to be called into question; no equivalent scrupulousness exists in Prévert. His quips (“He’s dead, but why should I go to his funeral since I’m perfectly sure that he won’t go to mine?), of which several are comprised here as single poems (and within poems), cannot stand up to the deep-probing, aphoristic meditations on death by Pierre-Albert Jourdan (1925–1981) or to those, more similar in their gallow’s humor, by Georges Perros (1923–1978). “Parole” is “logos” in Greek, but Prévert (unlike Perros, who likewise cherished daily life and championed la langue populaire) does not seem to have been affected whatsoever by Martin Heidegger’s meditations on the poetic logos as so many other French poets have been. Even when Prévert’s subject matter is grave (war, love, death), his verse can seem light in a land of heavyweights.

But there are exceptions. One is the longish “The Shadows,” which features two lovers sitting across from each other, presumably in a café. The piece begins with two of those trite metaphors (“shining light of love,” “happiness’s music playing”) usually banned from contemporary poetry. However, Prévert extends them, transforms them into more mysterious, more thought-provoking images and ideas. The “light of love” casts a shadow

. . . on the wall

your shadow

is spying on all

the moments of my life

and my shadow too

does quite the same

eyeing your liberty

And yet I love you

and you love me

the way one loves the daylight and life or summer.

This essential question as to whether genuine love entraps, possesses, and suspects or rather grants liberty to the other person, leads to an exploration of the difficulties of loving when

our two shadows chase each other

like a brace of hounds

loosed from a single chain

but each ill-disposed to loving

faithful to none but their master

their mistress too

and who

patiently wait

but trembling with chagrin

for the lovers to draw apart.

Norman Shapiro is a professor of Romance Languages at Wesleyan University; he has written a number of award-winning translations.

Perceptible through this metaphor, which is then transmuted a third time into a death scene involving the hounds and the lovers’ bones, is a sensitivity to the Other—the lover facing the poet—that runs deeper than the facile melancholy of other erotic or amorous poems included in this volume. In contrast, a five-liner such as “I fall asleep birds fill my eyes / I dream of garden loveliness / Far from our eyes contrariwise / I fall asleep tears fill my eyes / And my dream bears the name: distress” seems juvenile. Prévert is often strongest in his long poems, which give his metaphors room to metamorphose and to blossom new meanings and vantage points, a subtler aspect of his talent than is visible in his quirky jokes, satirical vignettes, and anti-militaristic statements.

Shapiro’s enthusiasm as a translator is felt not only in the versions themselves but also in his introduction and notes. He relishes finding equivalents for Prévert’s rhyming, which induces him to take some justifiable liberties in regard to the original. In a few places, he maintains some unidiomatic, post-positioned adjectives that become pardonable and jocular when the second rhyme falls. Note “dental” and “gentle” in “The Speech on Peace”:

showing his teeth mouth open wide

(. . .)

the carie dental

that flaws his pro-peace argument lays bare inside

the painful nerve the “nerve of war”

(alias “money”) a matter to be wrangled for

in manner gentle.

At the same time, Shapiro is careful about getting alternative meanings of single, resonant French words or phrases into the English and about drawing out hidden allusions. In “One Man’s Blessing,” for example, he adds three (rhyming) lines so that Christian imagery will be more apparent. The most brilliant and meticulous paraphrasing occurs in “Picasso Out Strolling,” of which Shapiro remarks, too modestly: “A certain amount of re-handling and re-positioning—translator’s license?—has been called for to preserve the core of the many apple allusions: lexical, religious, and political.” The core of the Prévert’s apple indeed! This is what we get in this extensive intelligent selection, a true labor of love.

=====================================

John Taylor is an American writer, critic, and translator who has long lived in France. The third volume of his critical panorama, Paths to Contemporary French Literature, will be published in June by Transaction Publishers. At the same time his translations of work by Philippe Jaccottet (And, Nonetheless, Chelsea Editions), Pierre-Albert Jourdan (The Straw Sandals, Chelsea Editions), and Jacques Dupin (Of Flies and Monkeys, The Bitter Oleander Press) will be appearing. He has recently received grants from the Sonia Raiziss Charitable Foundation to translate Louis Calaferte’s Le Sang violet de l’améthyste and from the National Endowment for the Arts to translate Georges Perros’s Papiers collés. He has written five books of stories, short prose, and poetry, the latest of which is The Apocalypse Tapestries (Xenos Books).