Theater Review Round-up: Our Man in London

It should be pointed out that in London it is possible to see more shows in a limited time than one can do in the United States. Why? Because it has long been the sensible practice to stagger weekday matinees.

By Caldwell Titcomb

Shakespeare first, of course. The British quite rightly never tire of “Hamlet.” A 23-year-old Ben Whishaw gave us a remarkable Prince in 2004, directed by Sir Trevor Nunn. Last year the Scottish actor David Tennant, at 37, received acclaim for his Hamlet (which I did not see), winning two awards. This year’s Hamlet (Wyndham’s Theatre) is 36-year-old Jude Law, under Michael Grandage’s direction.

Jude Law's outstanding Hamlet meditates on To be or not to be during a snowfall.

Law is outstanding all the way. His diction is unflaggingly clear and compelling. He gestures with one or both hands more than do most actors, but this invariably fits what he is saying. The “To be or not to be” soliloquy takes place during a snowfall. In a neat touch, Hamlet on seeing contiguous thrones for Claudius and Gertrude makes a point of separating them. The closet scene contains an unusual staging: the arras drops with Gertrude and Hamlet beyond it, and Polonius (an admirable Ron Cook) eavesdrops on the audience’s side when he is killed by Hamlet’s sword thrust in our direction. Kevin McNally’s Claudius and Penelope Wilton’s Gertrude are adequate but not outstanding. (This modern-dress production comes to New York in mid-September for a three-month run.)

“All’s Well That Ends Well” (National: Olivier), updated in time, gets an attractive mounting under Marianne Elliott’s direction. The heroine Helena (a warm Michelle Terry) cures the French King (a forceful Oliver Ford Davies), who rewards her with the husband of her choice. For some reason she chooses Bertram, a bigoted cad, who poses seemingly impossible conditions and goes off to war in Italy. The old bed trick is carried out in silhouette behind a sheet, and one wonders whether the play’s title is accurate. Clare Higgins is fine as the elderly Countess, and one could not ask for a better Lord Lafew than Michael Thomas provides. (There will be an international live broadcast of the October 1 performance.)

Hermione (Rebecca Hall) and Leontes (Simon Russell Beale) in the Bridge Project's production of The Winter's Tale.

Director Sam Mendes has set up the Bridge Project, which uses a bi-national company of British and American actors. Having played at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the troupe is ensconced at London’s Old Vic prior to an international tour. Despite the sometimes jarring accents, it has a success with “The Winter’s Tale,” one of Shakespeare’s half dozen greatest plays. Simon Russell Beale is superb as the jealous Leontes, who wrongly accuses his wife Hermione of adultery with his friend Polixenes. The peasant frivolity in Bohemia is colorful and mildly bawdy, and enhanced by the delightful Ethan Hawke as the guitar-playing rogue Autolycus. In the powerful final scene, the purported statue of Hermione stands with its back to the audience; when it comes to life, Leontes extends a remorseful hand, but Hermione does not take it.

The same company is offering Chekhov’s “The Cherry Orchard” in repertory. The proportions of comedy and tragedy will vary depending on the director. Sinéad Cusack’s Ranevskaya is not memorable, though Russell Beale’s Lopakhin, who at one point overturns all the chairs, is first-rate, as is to be expected. In any production the ending, with the 87-year-old servant Firs (Richard Easton) forgotten and abandoned to die alone, ought to be ineffably moving, but isn’t. Still, Sir Tom Stoppard’s new version, based on Helen Rappaport’s literal translation, is excellent.

Phèdre (Helen Mirren) clings to Hippolytus (Dominic Cooper) in the National Theatre production of Phèdre.

Under Nicholas Hytner’s direction, Helen Mirren is starring in a revival of Racine’s masterly “Phèdre” (National: Lyttelton). Designer Bob Crowley has provided a grand rocky set, sun-drenched by lighting designer Paule Constable. As the Queen of Athens, Dame Helen has fallen passionately in love with her stepson Hippolytus (Dominic Cooper), while her husband King Theseus is away and reported dead. She is tormented but can’t help herself. Her nurse Oenone, the always formidable Margaret Tyzack, urges her mistress to lie. Half way through the play Theseus (Stanley Townsend) turns up alive. Alas, his diction is poor and he seems to have wandered in from another play.

Too bad, since the rest of the cast is so strong, including John Shrapnel, who as Hippolytus’ counselor, has to recount at great length the death of his student. This production uses the 1998 English version by the late Poet Laureate Ted Hughes, adopted for several mountings. But it is not Racine, who wrote the 1677 play in rhymed couplets. How much better it would have been to use the rhymed 1986 translation by Richard Wilbur. Consider this excerpt from the Queen’s farewell speech:

Hughes:

The sword would have been my own choice, before this,

But that would have left the Prince’s innocence

To the play of suspicion and conjecture.

I have chosen a slower conveyance

To the land of the dead. This has allowed me

Time to show you, Theseus, my remorse.

Now I am drunk on an infallible poison

That my sister Medea brought from Athens.

Wilbur:

Much though I wished to die then by the sword,

Your son’s pure name cried out to be restored.

That my remorse be told, I chose instead

A slower road that leads down to the dead.

I drank, to give my burning veins some peace,

A poison which Medea brought from Greece.

The June 25 performance was broadcast to some 170 movie theaters around the world. And in late September the production will play for a week in Washington, D.C.

In J. B. Priestley’s “Time and the Conways” (National: Lyttelton), the unusual feature is that the first and third acts take place in 1919 while the second is a vision of 1937. The widowed Mrs. Conway and her six children are celebrating the 21st birthday of Kay, who hopes to be a famous novelist. In the second act all the characters are unhappy, and Kay has become a run-of-the-mill journalist. Director Rupert Goold has not obtained engrossing framing acts, but the middle act provides a magnificent performance by Francesca Annis as the mother – she reminded me of the celebrated actress Eva Le Gallienne.

Several new plays are substantially political in one way or another. The best of these is Ronald Harwood’s “Collaboration” (Duchess), directed by Philip Franks. In 1995 Harwood wrote a play entitled “Taking Sides,” which dealt with the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886-1954) and his alleged ties to the Nazis. The playwright unfortunately stacked the deck by making the American investigating officer a cultural numbskull.

Isla Blair and Michael Pennington in Collaboration. Photograph: Tristram Kenton

Harwood has now written a companion piece that explores the relationship of the composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949) to the Nazis. The two plays are now playing in repertory; and since I saw the earlier play years ago I went to see the new one. Here Strauss gets into trouble by collaborating with the famous Jewish writer Stefan Zweig as the librettist of his opera “Die Schweigsame Frau” (based on Jonson’s “The Silent Woman”). When Strauss is visited by a Nazi cultural official, he remarks, “I composed music under the Kaiser and during the Weimar Republic. Music is indifferent to regimes.” But the official complains that Strauss’ earlier librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal was a quarter-Jew, that Strauss’ daughter-in-law and grandchildren are Jewish.

There is fine discussion about artistic creativity between Strauss (Michael Pennington) and Zweig (David Horovitch). Pennington’s eventual testimony before the Denazification Board is just shattering. (I have never understood why he has not been knighted; he is one of the finest senior actors as well as the author of important books on “Hamlet,” “Twelfth Night,” and several non-Shakespearean dramatists).

Nicholas Hytner was at the helm of Richard Bean’s energetic comedy “England People Very Nice” (National: Olivier). It has a large multiethnic cast of 22, who – in a prologue and epilogue – play themselves as a director gives them notes. Using projections and occasional songs, the internal four acts portray the waves of immigration to England over the centuries: French Huguenots, the Irish, the Jews, and the Bangladeshis. A pair of lovers in their twenties recur in the four groups. The show provides a good many laughs amid all the interethnic friction.

Sir Richard Eyre has directed Matt Charman’s “The Observer” (National: Cottesloe). The play takes place in a fictitious, Igbo-speaking former colony in West Africa. (Some of the dialogue is in Igbo, which is mostly found in parts of Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea.) With doubling, the 23 characters are performed by a company of twelve. The work centers on the international election observation team before, during and after the first democratic elections. The main focus is on the team’s deputy chief, Fiona Russell (Anna Chancellor), and her translator, Daniel Okeke (Chuk Iwuji). Eventually the question arises whether Fiona has overstepped her authority and acted to affect the outcome. Both Chancellor and Iwuji give stunning performances.

Hanif Kureishi, son of a Pakistani father and English mother, is probably best known for his award-winning 1985 screenplay “My Beautiful Laundrette.” He garnered huge praise for his 1995 novel “The Black Album.” I have not read the novel, but he has now turned it into a play of the same name (National: Cottesloe). Partly autobiographical, it tells the story of Shahid Hasan, who goes from rural England to attend college in London, where he joins a group of radical fundamentalist Muslims who want to purge him of some Western ideas.

The play takes place at the time of the 1989 fatwa proclaimed against (now Sir) Salman Rushdie for his allegedly blasphemous “The Satanic Verses.” Shahid believes that “literature is not a political party” and cites Milton’s statement that “he who destroys a good book kills reason itself.” Riaz al Hussain, leader of the Muslim brothers, counters, “A religion that’s lost its hatred is not a religion – it is empty!” Much of the dialogue is awkward, and having 18 people played by nine yields considerable confusion. As directed by Jatinder Verma, Jonathan Bonnici is an appealing Shahid.

Stella Feehily has written “Dreams of Violence” (Soho), directed by her husband Max Stafford-Clark. This surprisingly amusing 90-minute play belongs to the Dysfunctional Family genre. It focuses on fortyish Hildy, who is divorcing but still sleeping with her philandering husband. She has to cope with her boozing mother, a former pop singer; her ex-addict son, who tells her, “You smell of menopause. I hope you die”; her wacky father, who urinates in the corner of his nursing-home room. A committed socialist, she spends daytime working to get better pay for women who clean offices – she tells them, “I care because I hate greed.” For her pains she winds up in the hospital from a heart attack. As Hildy, Catherine Russell could not be better.

Caryl Churchill’s one-hour, three-scene play “Three More Sleepless Nights” (National: Lyttelton) premiered in 1980 and is back in a short revival directed by Gareth Machin. The set is simply one double bed. Scene 1: Margaret (Lindsay Coulson) and Frank (Ian Hart). Scene 2: Pete (Paul Ready) and Dawn (Hattie Morahan). Scene 3: Pete and Margaret. No sex; everyone is ill-at-ease. The most striking skit is the second, in which Pete drones on about science-fiction movies without even noticing that Dawn has slit her wrist and blood is seeping through the bedsheet. All four players are admirable.

Juliet Stevenson and Henry Goodman (both Olivier Award winners) in Duet for One

Also dating from 1980 is Tom Kempinski’s two-hander “Duet for One” (Vaudeville), revived for two of Britain’s finest players – Juliet Stevenson and Henry Goodman (both Olivier Award winners). This play, directed impeccably by Matthew Lloyd, was inspired by the late virtuoso cellist Jacqueline du Pré (1945-87), whose career was stopped in 1973 by the onset of multiple sclerosis. In the play it is a violinist, Stephanie Abrahams, who contracts the disease, and, urged by her husband, has a half dozen sessions with a German psychiatrist, Dr. Alfred Feldmann, in his consulting room. Lez Brotherston has designed a gorgeous set, with shelves full of LP and CD recordings and airy windows with greenery beyond.

From time to time we hear bits of Bach’s unaccompanied violin sonatas. Stephanie is always in a motorized wheelchair, from which she terrifyingly gets up only to collapse on the floor. She is highly emotional and moody. Feldmann is unfailingly calm, jotting notes on a pad, until in the fifth session he finally blows his stack and accuses her of playing “stupid and boring games.” Both players exhibit consummate acting all the way, and at the end it is not clear whether there will be a seventh session.

Nina Bawden’s 1973 novel “Carrie’s War” was adapted for the stage a few years ago by Emma Reeves and is now back again (Apollo), directed by Andrew Loudon. It tells the story of Carrie Willow and her brother Nick, who are evacuated to Wales during World War II. They live with a bullying Mr. Evans and his warmhearted sister – stereotypes both – and befriend another evacuee, Albert, who stays with Mrs. Gotobed (Mr. Evans’ sister), as well as the ridiculed Mr. Johnny, who is afflicted with cerebral palsy. In Act 1 we get a recorded snippet of a speech by President Roosevelt, and in Act 2 an excerpt of Churchill. The whole affair is too saccharine and unimaginative. The only star in the cast is Prunella Scales (now 77) as Mrs. Gotobed, but she has little to do and does that little tentatively.

Tom Stoppard’s dazzlingly brilliant play “Arcadia,” first mounted in 1993, has been revived under David Leveaux’s direction (Duke of York’s). It covers so many subjects that a capsule summary is impossible. Much of it deals with mathematics and physics – but done with passion and heart. The special device is that the country-house setting remains constant but the occupants alternate between 1809 and 1989. What really happened in the past? Did the unseen Lord Byron kill a man in a duel? Scholars interpret evidence differently, but order can emerge from chaos. The cast of twelve is uniformly superb – including Ed Stoppard, the playwright’s son. There is talk of a New York transfer.

It is often recalled that some 800,000 British fighting men were killed in World War I. But few realize that a million horses were sent to France, of whom only 62,000 came home after the armistice. It is the latter fact that inspired Michael Morporgo to pen his 1982 novel “War Horse,” aimed primarily at young readers. Adapted for the stage by Nick Stafford, the show opened two years ago in the National’s Olivier theatre, and proved such a colossal hit that it moved this year to the New London Theatre, where it is booked into next year.

A scene from War Horse with mounts courtesy of the Handspring Puppet Company

The drama tells of young Albert (nicely played by Kit Harrington), whose horse, Joey, is taken and shipped to Flanders, where Albert goes to look for him. The major attraction is the appearance of one horse after another, each operated from within by three persons (courtesy of the Handspring Puppet Company). Several horses are eventually shot in battle. Back home there is also a frisky goose operated by a puppeteer. This spectacular show appeals to all ages.

Quite different is the premiere of “The Mountaintop” (Trafalgar Studio), an intimate two-hander by Katori Hall, a 28-year-old black American playwright. Born in Memphis, Tennessee, she attended Columbia University, got a master’s degree in acting from Harvard’s American Repertory Theatre Institute, and studied playwriting for two years at Juilliard.

David Harewood and Lorraine Burroughs in The Mountaintop

This play is about the last night before Martin Luther King’s assassination. He has just given his famous Mason Temple speech asserting that “I have been to the mountaintop and I’ve seen the promised land.” Now he is unwinding in Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel, and orders something brought by a chambermaid named Camae. They chat both humorously and seriously, and after a while it turns out that Camae is not quite what she seemed to be. Under James Dacre’s direction, David Harewood is magnificent as Dr. King; he has King’s accent and inflections down cold. As Camae, Lorraine Burroughs is wonderfully chameleonic. Surely American productions are in the olffing.

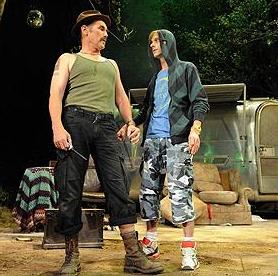

Jez Butterworth’s latest play, “Jerusalem” (Royal Court), is shocking, sprawling, in-yer-face…and hilarious. It takes place in and in front of a run-down mobile home sitting in a clearing in the woods. Lording it over everyone and everything is Johnny “Rooster” Byron (Mark Rylance), a tattooed 50-year-old ex-daredevil and spiller of tall tales (“My mother was a virgin when she bore me”). He is a charismatic figure who attracts people of all ages – especially teenagers, whom he supplies with booze and drugs (he calls them “my band of educationally subnormal outcasts”). Twice the local officials try to serve him an eviction notice, which he finally takes and sets fire to as he pulls out another bottle of whiskey.

Mark Rylance and Mackenzie Crook in Jerusalem (Photo: Alistair Muir)

Rylance is an actor of amazing range (he won the best-actor Tony Award this year for his Broadway performance in the godawful “Boeing-Boeing”), and his work here is absolutely astonishing; I can’t think of another actor in the world who could match it. Ian Rickson has directed his 14 players flawlessly.

Turning to musicals, Sir Trevor Nunn has mounted a charming revival of the 1973 Sondheim/Wheeler “A Little Night Music” (Garrick), with only a few excessive comic bits. Based on Ingmar Bergman’s 1955 movie “Smiles of a Summer Night,” it wittily explores several mismatched couples. Except for the 18-year-old Anne, the characters have been solidly cast. The standouts are Hannah Waddingham as the actress Desiree and Maureen Lipman as her wheelchair-bound and moribund mother Mme. Armfeldt. Lynne Page has provided lovely choreography for the “weekend in the country.”

Another film-based musical is “La Cage aux Folles” (Playhouse), which started out as a 1973 French stage farce by Jean Poiret and then became a 1978 movie. Jerry Herman and Harvey Fierstein fashioned the award-winning musical in 1983, which deals with a gay couple, Georges and Albin, the latter of whom is a transvestite performer. Georges is played by Philip Quast, who is a splendid singer. Roger Allam is a seasoned actor but his Albin is, frankly, not well sung. Terry Johnson has directed, and once again Lynne Page is the fine choreographer. The six dancers in drag, known as Les Cagelles, are flawless. Although Broadway saw a revival of the work in 2004, this London version will come to New York in the spring with Douglas Hodge as Albin.

London native Adam Cooper, a former principal in the Royal Ballet, conceived, directed, choreographed, and stars in a show entitled “Shall We Dance” (where’s the question mark?), styled as “A Tribute to Richard Rodgers” (Sadler’s Wells). No singing, so no Hart or Hammerstein. It sports a large cast of two dozen and a full orchestra on an upstage platform. What passes for a story shows us Cooper, as The Guy, traveling the world to find The Right Girl, who materializes on the seventh try.

The show uses excerpts from a dozen Rodgers scores – not just the classic “Oklahoma!,” “South Pacific,” “Carousel,” and “The King and I,” but lesser-known efforts like “No Strings” and “Ghost Town.” There are even a half dozen items from the virtually forgotten “Flower Drum Song.” It all adds up to a moderately appealing event, but one longed for something more.

Finally, it should be pointed out that in London it is possible to see more shows in a limited time than one can do in the United States. Why? Because it has long been the sensible practice to stagger weekday matinees – some of them on Tuesday, some on Wednesday, some on Thursday, some on Friday. In addition, this year for the first time the National Theatre (with its three venues) is scheduling performances of its rotating repertory on all seven days of the week. Stage fans, rejoice.

Tagged: “The Black Album, All's Well That Ends Well, Anton Chekhov, Arcadia, Bridge Project, Caldwell-Titcomb, Carrie's War, Caryl Churchill, Collaboration, Cottesloe, Dreams of Violence, Duet for One, Dysfunctional Family, England People Very Nice, Ethan Hawke, Francesca Annis, Hamlet, Hanif Kureishi, Helen Mirren, Henry Goodman, J. B. Priestley, Jerusalem, Jez Butterworth, Jude Law, Juliet Stevenson, Katori Hall, Lyttleton, Mark Rylance, Matt Charman, Max Stafford-Clark, Michael Grandage, Michael Morporgo, National-Theatre, Nazis, Nicholas Hytner, Olivier, Phèdre, Racine, Rebecca Hall, Richard Bean, Richard Strauss, Richard Wilbur, Ronald Harwood, Sam Mendes, Simon Russell Beale, Sinéad Cusack, Sir Richard Eyre, Stefan-Zweig, Stella Feehily, Ted Hughes, The Cherry Orchard, The Mountaintop, The Observer, The Silent Woman, The-Winters-Tale, Three More Sleepless Nights, tom-stoppard, War Horse, William Shakeseare