Opera Review: Galuppi’s “L’amante di tutte” — A Total Hoot!

By Ralph P. Locke

A delightful and compact opera — from a generation before Mozart — that cuts various social types down to size.

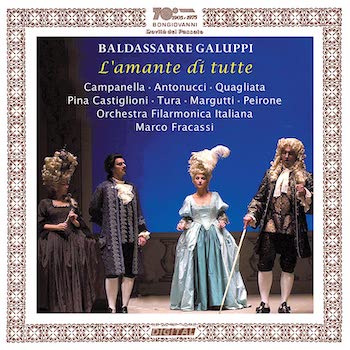

Baldassare Galuppi: L’amante di tutte (The Man Who Loved Any Woman; 1786)

Linda Campanella (Clarice), Paola Quagliata (Dorina), Paola Antonucci (Lucinda), Filippo Pina Castiglioni (Count Eugenio), Roberto Tura (Don Orazio), Corrado Margutti (Mingone).

Piacenza Italian Philharmonic Orchestera, cond. Marco Fracassi.

Bongiovanni 2318-3—78 minutes

Click here to purchase or to listen to the beginning of each track.

I have hailed various recently revived Classic-era operas here and in American Record Guide, including a marvelous comic one by Paisiello that is set in Boston, Le gare generose (1786). But this opera by Galuppi (1706-85) was composed 26 years earlier, in 1760, and, typically for works in the Early Classic Era, is far more compact. The arias and other numbers have none of the expansiveness so dear to opera lovers in works of Paisiello, Cimarosa, Haydn, Salieri, or Mozart. (Mozart was only four years old when this Galuppi opera reached the stage.)

I have hailed various recently revived Classic-era operas here and in American Record Guide, including a marvelous comic one by Paisiello that is set in Boston, Le gare generose (1786). But this opera by Galuppi (1706-85) was composed 26 years earlier, in 1760, and, typically for works in the Early Classic Era, is far more compact. The arias and other numbers have none of the expansiveness so dear to opera lovers in works of Paisiello, Cimarosa, Haydn, Salieri, or Mozart. (Mozart was only four years old when this Galuppi opera reached the stage.)

Two instances: A teasing duet for Dorina and Mingone (soprano and basso) is over in 40 seconds. I followed along with the manuscript (at IMSLP.org), and indeed the thing is a total of 10 measures long. Then, after a minute of recitative, Dorina sings an aria that lasts all of 2 minutes and 5 seconds. Even within that short span, her aria manages to flit from one rhythmic figure to another several times.

The whole opera is constantly on the move and fits onto a single CD. Its music is almost continuously cheerful, except for an occasional brief turn to the minor. One lovely aria is a lament in Neapolitan style (almost entirely in the minor) for the servant Mingone (see below) begging forgiveness for having tricked his master. The conductor here nicely reduces the orchestra to one-on-a-part, increasing the (ironic) mood of sorrowful pleading.

Various arias include humorous lists of enumerations: “one, two, three”; or “Spain, Italy, Europe, Asia, Africa, America.” (One sees here a tradition that Leporello’s Catalogue Aria will draw upon in Mozart’s Don Giovanni.) The second-act finale is more complex than the rest, and well worked out. All in all, I can see why the opera was so successful in its own day, achieving more than 20 productions in various cities and towns in its first decade.

Alas, the record company, Bongiovanni, provides no essay, synopsis, or libretto, and the track list most often identifies only one character per track, even for a track in which several characters wrangle with each other in quick recitative. I was mostly lost at first. Enjoyably lost, it is true, since the singers are all native Italians and project well. Still, I could have used at least some background information, including indications of who is or are onstage at a given time and who each character is addressing or arguing with. (Maybe it’s me: I often confuse one light soprano with another.) A brief synopsis in OxfordMusicOnline.com helped me somewhat, telling me which of three women a given man was pursuing, conspiring with, or suspicious of at certain moments.

Soprano Paola Quagliata. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

I did finally locate online a printed libretto from 1770 that largely, though not completely, matches what is heard here. The detailed cast list reveals (write this down!) that Don Orazio is an elderly nobleman, Lucinda is his wife, Dorina is Lucinda’s maid, and Clarice is a donna affettata (presumably meaning a woman with somewhat affected or pretentious manners). Mingone is a peasant on the country estate of Don Orazio, where the action takes place. Count Eugenio is the opera’s title character, the “Lover of All Women.” The Marquis Canoppio (a third nobleman) has become impoverished but remains proud of his exalted rank.

The opera ends with Don Orazio threatening to lock his wife up. She and the other characters kneel before Orazio and beg him to forgive the woman, who, they say, has now reformed. The haughty (though destitute) Marquis adds that his high social position should make it difficult for Orazio to refuse this request. Soon after, Orazio does comply, and everyone joins in a chorus of “Let bygones be bygones.”

I found pleasure in listening to the work several times through, not least because the singers are clearly enjoying themselves. I particularly appreciated the performances of the two sopranos (Linda Campanella and Paola Quagliata). The other cast members manage their roles capably, though they are, to varying degrees, less firm of voice. The chamber orchestra plays delightfully, giving special pleasure in numbers that feature woodwind solos and string-orchestra pizzicatos. The recording was made during a staged performance in Piacenza in 2000, and the audience, too, is clearly having fun yet is, fortunately, quiet most of the time.

Ah, but how much more we could have gained from the recording if there had been an essay, a full synopsis, an informative track list, and a libretto in the original and translation. Bongiovanni should remember the international community of CD collectors. The current release is already available to me—and probably to many of my readers—in a streamed version through Spotify or other services and, in my case at least, through my library’s Naxos Music Library subscription. Why, then, should we spend money to own the same recording on CDs and remain just as baffled?

Still, there is much to be gleaned from the recording and the info that I provided above (or you can peek at the Italian libretto yourself at the link I give above).

I recommend the recording heartily, and hope that it may also spur some productions from music-school and regional opera companies. This might include, in New England, Odyssey Opera (always looking for novel fare to promote), Boston Lyric Opera, and the opera studio at the New England Conservatory or other colleges and universities.

An alert singing translation would make it a total hoot!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Baldassare Galuppi:, Bongiovanni, L’amante di tutte, Paola Quagliata

[…] CD/DVD Opera Review: Galuppi’s “L’amante di tutte” — A Total Hoot! A delightful and compact opera — from a generation before Mozart — that cuts various social types down to size. https://artsfuse.org/216605/opera-review-galuppis-lamante-di-tutte-a-total-hoot/ […]

[…] the very engaging Myto re-release), along with such other comic operas from around the same time: Galuppi’s L’amante di tutte and Paisiello’s La grotta di Trofonio. As for opera lovers, generally, if they are not fluent in […]