Book Review: “The Swimmer” — Wading Through the Ripples of History

By Tess Lewis

A new novel captures the atmosphere of post-1956 Hungary from a child’s point of view.

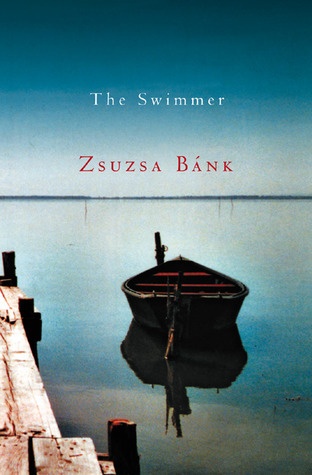

The Swimmer by Zsuzsa Bank. Translated from the German by Margot Bettauer Dembo. (Harcourt Books)

In tales of exile, the stories of those left behind are rarely told. This is hardly surprising because the abandoned, when they are not targets of a dictatorship’s reprisals, spend much of their time waiting and wondering, occupations without much dramatic flair. In Zsuzsa Bank’s moving first novel, The Swimmer, however, the waiting and the wondering are raised to a pitch of intensity that courts disaster.

In tales of exile, the stories of those left behind are rarely told. This is hardly surprising because the abandoned, when they are not targets of a dictatorship’s reprisals, spend much of their time waiting and wondering, occupations without much dramatic flair. In Zsuzsa Bank’s moving first novel, The Swimmer, however, the waiting and the wondering are raised to a pitch of intensity that courts disaster.

The teenaged narrator, Kata, was only three years old when her mother, Katalin, left their home in a small Hungarian village, just as she had every morning for her job in a textile factory. The year was 1956, and the repression that followed the failed uprising against the Soviets had just begun. But the political and personal circumstances surrounding Kata’s mother’s decision to leave for the West emerge only gradually and incompletely. Bank’s own parents left Hungary for Germany as part of the mass exodus in 1956. Born in Frankfurt nine years later, the author learned second-hand of the time and place she evokes so deftly in The Swimmer.

The story’s told from the perspective of a child who sees far more than she understands. Kata notes that her father treasures a particular picture of her mother standing in a field with a metal food container, wearing a kerchief knotted under her chin and sandals with straps tied around her ankles: “Nobody wore sandals in those days, certainly not in the fields.” Even as a young child she recognized hints of her mother’s defiance in details as trivial as an ankle strap. Bank’s spare, evocative prose is particularly well-suited for capturing the mysterious, half-understood world of children as it is suggesting the atmosphere of half-truths and evasions that stifled Eastern Europe for so many decades.

When Kata’s father studies pictures of his missing wife, he falls into a trance, becoming oblivious of his surroundings for days at a time and looking at his children as if they were strangers. Kata and her younger brother, Isti, call it diving: “We’d ask each other — has Father come back from diving?” Even on good days their father rarely took notice of Kata and Isti, except near any body of water. He would swim and play with his children in the water for hours, eventually teaching them to swim. But out of the water, he was inaccessible.

Kata tells her story in muted, almost deadpan tones all the more powerful for their lack of overt emotion. “My mother didn’t say good-bye to us that day. She went to the train station, just as she had done on so many other days. She boarded a train headed west, for Vienna. I knew how rarely such trains left our station. My mother must have waited a very long time for it; she must have had time to change her mind.”

As the finality of Katalin’s departure sinks in, K??withdraws almost completely into himself, leaving Kata to take charge of Isti. In fact, the two are left mostly to themselves as their father drags them across the country, moving in with various relatives and friends until they wear out their welcome and must move on again. The loss of his mother is more than Isti can endure and he takes up his own form of ‘diving.’

The boy begins hearing sounds and voices from the objects around him. He hears screams from hair that is cut, moans from the wood in the walls, even the grapes on the vines speak to him, though the red far more clearly than the green. He disappears for hours at a time and begins swimming compulsively. The water’s suspension of gravity is Isti’s only refuge, yet this symbol of freedom, like so much in B?’s subtle novel, is dangerously ambivalent.

Katalin writes letters now and then, mostly to her own mother so as not to endanger K??and her children. Few survive the censors’ filters. Kata learns much later that her father had been interrogated repeatedly about his wife’s departure even though he could tell the authorities nothing.

After several years of their nomadic existence, the children’s maternal grandmother returns from a visit to Germany with news of Katalin. She found work as a dishwasher in a cheap restaurant. Her new life has been every bit as limited and impoverished as it was in the village she fled. But she will not come back, so there is no longer any use pretending for the sake of the children. “At some point, all you can do with this life is endure it … but K??s wife wasn’t suited to enduring,” a relative announces before concluding that they are all forced to put up with the life for which they are destined.

Only the ripples of history reach the characters in their Hungarian backwater. Rumors of a wall built to divide Berlin or a student setting himself on fire in Prague in protest against the Soviet invasion are barely noticed or even believed. Yet they underscore the sense of lethargy and isolation that weighs so heavily on Kata and her relatives and that her mother was so desperate to escape. The Swimmer ends with Kata, also unwilling to endure, waiting for her exit visa.

Tess Lewis’s translations from French and German include works by Walter Benjamin, Peter Handke, Klaus Merz, and Christine Angot. Her translation of Maja Haderlap’s Angel of Oblivion was awarded the 2017 PEN Translation Prize. She is co-chair of the PEN America Translation Committee and an Advisory Editor for The Hudson Review.