Jazz CD Review: Pianist Erroll Garner — Remastered Sessions from His Prime

By Michael Ullman

Octave is issuing twelve sessions (“newly restored and expanded”) of Erroll Garner material from the ’60s and ’70s, when the popular pianist was at the height of his career.

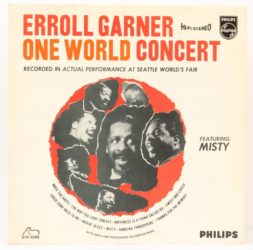

Erroll Garner: Dreamstreet (1959) Closeup in Swing (1961); One World Concert (1962); A New Kind of Love (1963). (Mack Avenue and Octave).

In 1955, already a veteran recording artist — he first went into the studio in 1944 — pianist Erroll Garner recorded his Concert by the Sea, which became one of the best-selling jazz records of its time and perhaps of all time. It almost didn’t happen. The story is that when Garner was about to go on stage, his manager Martha Glaser spotted a tape recorder at Carmel-by-the-Sea’s Sunset School. She took control of the machine and, instead of a bootleg made for a few, she had a tape that was sold to Columbia Records and released to worldwide acclaim. (An expanded version, on three CDs, is now available as The Complete Concert by the Sea.) Already known as the composer of Misty (from 1954), Garner became one of the hottest acts in jazz.

He was an assertive star as well. Garner sued Columbia Records, his own label, for issuing a session of which he didn’t approve. As a result, he started his own publishing company, Octave. Octave is issuing twelve remastered sessions (“newly restored and expanded”) of Garner material from the ’60s and ’70s. Most of it has been previously released, but there is also some newly discovered bonus material. I am listening (on high quality downloads) to the first four releases, all from the height of Garner’s career.

No one sounds like him. And it is not clear where his distinctive style came from. His career started in the midst of the bebop era: he recorded with Charlie Parker, Don Byas, Lucky Thompson, and other modernists. But he never imitated Bud Powell or the light-fingered Teddy Wilson, the latter a typical model from the ’30s. Instead, the mature Garner attempts, with his two hands, to represent an entire big band. Famously, in his solo playing he offers a chomping 4/4 with his left hand, playing chords with a thumping regularity that always seems to be anticipating the beat. He draws on a grab bag of techniques. He often plays melodramatic introductions that have little to do with the tune to come. It’s a game he plays with listeners: they (and perhaps his accompanists) are left to guess whether they are about to hear “Sweet and Lovely” or “Sweet Lorraine.” Live audiences tend to applaud when they recognize the tune that is being played. Garner likes to suspend that satisfaction; his introductions are full of contrasts, gigantic tremolos punctured by sudden hushes that seem to imitate a cat walking. He might launch single notes that fan out in harplike sprays or are so distinct and percussive they almost sting, like darts. His introduction to “Movin’ Blues” gives us Garner at his harshest — busy chords tripping over each other, as if we are listening to a train, filled with iron scraps, rattling along.

Dreamstreet opens with a series of those aggressive chords, with little right hand figures forcing their way in. The tune turns out to be “Just One of Those Things.” Garner mostly plays hoary standards and his own compositions. Amusingly, on Dreamstreet he also performs a medley of tunes from the musical Oklahoma. He makes each piece his own. On Closeup in Swing, “St. Louis Blues” starts off as a kind of mambo before he begins to improvise in four. One World Concert shows, once again, how Garner is inevitably energized by a live audience. For this listener, “Mack the Knife,” already a staple of Louis Armstrong’s repertoire, is one of the disc’s highlights. (Bobby Darin would make a killing from it in 1959.)

The surprise set in this initial multidisc release is 1963’s A New Kind of Love, a session with orchestra made for a now (justly) forgotten romantic comedy. The movie is very dated: Paul Newman plays a journalist who interviews a character played by Joanne Woodward, whom he thinks is a prostitute. Humor inspired by the battle between the sexes was different in those days — but the music holds up, splendidly. So often the dominating center of things, Garner plays the role of a tactful, nuanced commentator on the orchestra. His performance here is as gentle as he gets. The soundtrack contains three versions of his “Paris Mist”: a trio version, a bossa nova (inevitably — it was 1963), and what they call a “waltz and swing version.” Garner starts the latter cut with chords as emphatic as the opening of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, which may have been a model. In these years Garner was consistently intriguing. Yes, he is an inventive improviser, but mostly he epitomizes what older musicians would call a stylist. These albums have left me looking forward to what else is to come out of Octave’s vaults.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: A New Kind of Love, Closeup in Swing, Concert by the Sea, Dreamstreet, Erroll Garner, Mack Avenue, Michael Ullman, Octave Records