Jazz Concert Review: A Third Report from the 40th Montreal Jazz Festival — Harmony Amidst Chaos

By Robert Israel

This year’s Montreal Jazz Festival Festival would have been more successful had it not been for all the construction ripping apart the city.

The 40th Montreal Jazz Festival was, for the most part, a marvel. At least given what I could see of the expansive event. At both indoor and outdoor venues I heard a cavalcade of top-notch performers who hailed from Canada, the States, Chile, Norway, and beyond. Standing sardined amidst throngs on Ste. Catherine Street in the heart of city’s center, I grooved to tunes while basking in the late Quebec summer twilight that lingered high in the sky long past 9 p.m.

The Festival would have been more successful had it not been for all the construction ripping apart the city. Montreal is repairing a crumbling infrastructure — in downtown, in Chinatown, in Old Montreal, and in the streets surrounding Marche Jean Talon, the city’s popular outdoor marketplace. Streets and sidewalks are pocked with open, fetid pits. Sandy pumice befouls the air. Pont Champlain — the main bridge that crosses the St. Lawrence — was closed: I often moved about (and about) in dead-ended circles; poor signage heightened my sense of malaise.

How do Montrealers cope with chaos? Marc Lebrèche, a Montreal-based stage performer and television personality, in an interview in the Arts Fuse, explained it best:

I come from a culture that has gone through so many hardships over so long a time and yet, like my fellow Quebecois, I am jovial, ebullient, cursed with an unquenchable joie de vivre.

It is this joy of life – with its inherent hardships and fleeting joys — that rules the day in Montreal, and that’s a splendid backdrop for jazz, a music born of struggle and repression. Jazz is capable of lifting our spirits and then, on the turn of a note, send those spirits on a downward spiral.

The set performed by Melissa Aldana, a Berklee College graduate, tenor saxophone virtuoso, composer, and bandleader, is a perfect example of juggling highs and lows: she performed both upbeat and dark hued tunes.

Melissa Alana — her music celebrates the achievements of Latinas. Photo: Harrison + Weinstein.

When Boston-area concertgoers last heard Aldana, it was during a Celebrity Series event for Monterey Jazz Festival on Tour at the Berklee Performance Center that offered only a glimpse of her talents. Her late night June 27 Festival performance in Montreal let her strut her stuff. Chilean-born Aldana showcased her own band (now on a world tour) and featured selections from her new recording, Visions.

From the stage at Le Gesu (a performance space carved out of the nave of a nineteenth century Montreal church), Aldana explained that her new album was inspired by the late Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. She’s aligned with “Los Fridas,” a group of fans formed in the 1940s, defined by Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts as an example of “Fridamania,” or “a fascination with all things Frida.”

For Aldana, Kahlo is not just an idol: the late Mexican painter embodies the struggles many Latinas, past and present, have faced in a culture that celebrates the achievements of men at the expense of women. In her composition “La Madrina” (“The Godmother”) she takes us on a “vision” quest with a Latin beat that resonates with street sounds and midnight wailings. A physical performer, she stoops her lanky frame low to bring forth the notes and then follows by rising up from bent knees, as if to encourage her tenor sax to hit the higher octaves.

Frida Kahlo’s paintings took viewers on a similar trip, tapping into a world of the subconscious, drawing on folklore and family ties that explored her Mexican traditions. Aldana, the daughter of Chilean saxophonist Marco Aldana (who tutored her as a youngster), honors her traditions while also setting herself on a fresh path. Her compositions echo approaches of Coltrane, Monk, and Getz, but she has created a distinctive sound. She is also a generous collaborationist. In one composition she interfaced with drummer Tommy Crane, who circled his cymbal with the wooden tip of his drumstick – the way one might wet one’s finger to produce a hum from the rim of a crystal glass goblet. Aldana carried that sound forth, catching Crane’s high, single note and, once grasping it, tunneling it low, mesmerizing the audience.

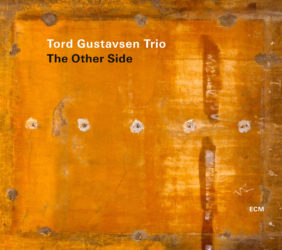

While Chilean saxophonist Melissa Aldana finds inspiration in Frida Kahlo, Norwegian pianist Tord Gustavsen finds his in the works of J.S. Bach and Montreal-born songwriter Leonard Cohen. Returning to Montreal after an absence of 11 years, Gustavsen entered the Gesu auditorium and proceeded to pay demonstrate why J.S.Bach lends himself to jazz interpretation.

He called Bach “a famous Buddhist” because the German composer excelled at mastering his inner life and emotions. Gustavsen admitted that “this is very dark music” but added, “it is from the deepest sorrows that we appreciate life.” A description of his fellow Quebecois that resembles the characterization of Marc Lebrèche.

Playing a Steinway grand, he produced darkly stirring notes, with warm complex tones punctuated by sudden bursts of rhapsodic lightness, along with lyrical bursts and well-timed pauses. He wove Norwegian folk tunes into his compositions, and freely interpreted Cohen’s verse from “Came So Far for Beauty,” a song that includes the refrain: “I came so far for beauty/I left so much behind/My patience and my family/My masterpiece unsigned.”

Loss, melancholy, the danker recesses of the human spirit: all this disappointment was a far cry from the upbeat vocals — and millennial-themed lyrics — of Quebecois singer Charlotte Cardin, who commanded the outdoor stage on June 27, riding on the popularity generated from appearances on numerous Canadian television shows. The 25-year-old chanteuse has not yet released an album, yet she is embarking on a world tour. Her voice is rousing; it lifts the crowd and moves them, like a strong wind. More of a pop, torchy vocalist than a jazz interpreter, she nonetheless suggested where jazz may be headed — embracing the kind of music that attracts large crowds, tunes saturated with a heavy doses of rock and electrics.

Singer Charlotte Cardin — a rousing voice.

Despite the noisy cacophony that came with the odious construction, Montreal still manages to do justice to the desire for music. In Old Montreal, near St. Suplice cathedral, a line of several hundred people formed to hear an organ recital; across the square, opposite the church, a flamenco guitarist with his own amp performed Spanish melodies. He later passed the hat for change. Around the corner, on St. Francois Xavier St., Bonaparte restaurant manager Martin Bédard told me that re-vamping his venerable establishment – it is housed in a building that dates from the mid-1800s – took over three years to complete. The old streets around the building are skinny and permits took forever to complete. The traffic snafus were abominable. And yet, despite all these hurdles and inconveniences, the work was successful. Today, the dining room shines.

And, no doubt, next year’s Montreal Jazz Festival will shine too, though there is not much of a chance Montreal will be able to reign in the construction. No doubt the throngs of international visitors will be challenged once again. In this sense, the Montreal Jazz Festival may be symptomatic of an increasing number of major cities that are trying to construct tourist havens — in the midst of de-construction.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Tagged: Melissa Aldana, Monreal Jazz Festival, Robert Israel