Theater Commentary: Drums in the Night — A Glimpse of the Real Weimar

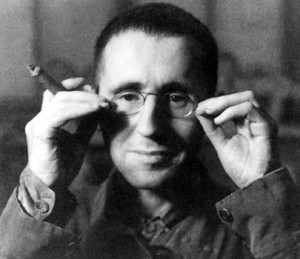

“My condition was like that of a man who has fired a gun at people he dislikes, and finds these same people coming and giving three cheers for him: inadvertently he had been firing loaves of bread. – Bertolt Brecht, “Drums in the Night’s Success With the Bourgeoisie”

By Bill Marx

Granted, some of Brecht’s regrets for the popularity of his early play Drums in the Night reflect youthful bravado, the giddy thrill of having fired off bullets and fired up the box office at the same time. (The 1922 premiere production also earned him a big award—the prestigious Kleist Prize.) Still, the play’s lyrical disdain for all classes and parties in post-WWI Germany is real, reflecting Brecht’s essentially apolitical, hedonistic vision before he turned to Marxism. A poem entitled “Born Later,” written by the dramatist around the time the play was produced, expresses his despair: “I admit it: I/ Have no hope./ The blind talk of a way out. I/ see. // When the errors have been used up/ As our last companion, facing us/ Sits nothingness.”

The American Repertory Theatre (A.R.T.) asks that its Institute productions not be reviewed, so I won’t, but those who want a compelling serving of the cool, cruel, anarchistic art of Weimar should take a look at this rarely produced play, whose final two performances will be presented today in the Loeb Experimental Theatre at the Loeb Drama Center in Cambridge. At the very least, the script serves as a welcome contrast to the ‘love me, love me’ sentimentality of The Blue Flower, the latter a visually attractive homage to Weimar culture that didn’t hand out bread but Swiss chocolates to the bourgeoisie on its opening night—let them eat candy.

Andreas Kragler, a traumatized solider thought to have been killed in Africa, returns after four years to claim his love but finds Anna engaged to a slick war profiteer and the city of Berlin in violent upheaval, Spartacists leading an uprising in the streets, the police and the army using guns and cannons to crush the communists’ calls for social justice. Though the ghostly Kragler sleepwalks through various allegiances in his absurd quest for a reluctant Anna, he ultimately refuses to accept the opportunistic cant of either the fatcats or the radicals, preferring his woman and a warm bed.

Thus the conventional romantic ideal (celebrated in The Blue Flower) becomes an anti-romance—it is the necessary, pleasurable, but nasty triumph of the libido in a culture dedicated to death. That notion of animal comforts trumping all, erotic gamesmanship serving as a means to control others, runs through other rookie Brecht script such as Baal. Perhaps Drums in the Night‘s surprising mainstream success came from how it probes society’s guilt about the plight of returning soldiers while supplying the sardonic reassurance that nothing could be done but to go home and have a roll in the hay with your significant other. For some, that looked like uplift.

One reason Drums in the Night isn’t produced often is that it is a bit of a mess. It opens with broad satire of the moneybags who stayed out of combat and who are now desperate to forget the war as soon as possible, despite mouthing bromides about enduring heroism. The easy jabs have some wicked kick: a manufacturer of ammunition boxes declares that with the war over he will make baby carriages, a witty send-up of the Biblical exhortation to turn swords into plowshares that also touches on the play’s obsession with fecundity.

Kragler encounters would-be revolutionaries in confusing scenes that, decades after the play’s premiere, Brecht jiggered with because of his political conversion. As a Marxist, the dramatist wants the audience to disapprove of his anti-hero’s choice of “a big, white, broad bed” rather than revolution—he should have gone off with his comrades and become a martyr. Brecht realizes that his revisions haven’t done the trick: “The reader or spectator had then to be relied on to change his attitude to the play’s hero, unassisted by appropriate alienations, from sympathy to a certain antipathy.”

Luckily, spectators and readers can think whatever they want; the angry rejection of Left and Right remains for me the strongest element in the play because it springs from Brecht’s visceral, expressionistic vision of the world as a frigid slaughterhouse. “It’s all a lot of make-believe, ” exclaims the weary soldier, “A few boards and a paper moon. The only thing that is real is the butcher’s block in the background.” In a sense, Kragler’s primal yearning for a warm bed, driven by his horrific memories of war, is also an anarchistic cry to be free of the delusions of hope fostered by plays such as The Blue Flower. Here is a real taste of Weimar culture.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: A.R.T. Institute, Bertolt Brecht, Drums in the Night, The Blue Flower