Theater Interview: Playwright Paula Vogel on “Indecent” and a Love of Yiddish

By Robert Israel

“Yiddish is above all a language of yearning, a language of anxiety.”

A scene from the Huntington Theatre Company production of “Indecent.” Photo: Carol Rosegg

My last interview with playwright Paula Vogel took place in 2009, when the Huntington Theatre Company staged her play A Civil War Christmas. This week, a decade later, we spoke about her new play Indecent — her retelling of the 1923 controversy that erupted when Yiddish writer Sholem Asch’s God of Vengeance was banned on Broadway, its cast arrested on charges of obscenity. Indecent had its New York premiere in 2016; nominated for several Tony awards, it reaped a single Tony presented to the play’s director, Rebecca Taichman. A Center Theatre Group and Huntington Theatre Company co-production of Indecent (at the Huntington Avenue Theatre, 264 Huntington Avenue) runs from April 26 through May 25.

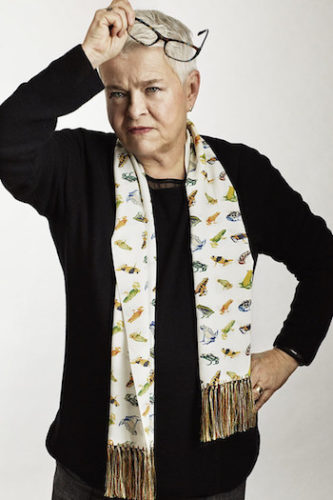

First, the back-story: Vogel, 67, lives in Wellfleet with her wife, author Ann Fausto-Sterling. Vogel is the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, an Obie, and the Robert Chesley award, among others. Now retired from full-time teaching at Brown and Yale (but not retired from what she calls “guest teaching”), she has, much like the early days of her career, been a champion for more resources being allocated to playwrights.

“I have a not-so secret strategy,” Vogel said, “and that is that I talk to my students as peers. When they leave my class, I tell them they leave as my colleagues. I treat the classroom as a workshop. I provoke students. I tell them that talent is not a survival of the fittest, it is a collaboration.”

Vogel’s former students include Pulitzer winners Nilo Cruz, Quiera Alegria Hudes, and Lynn Nottage, Gina Gionfriddo, a Pulitzer finalist, and HTC artistic director Peter DuBois. DuBois told Brown Alumni Magazine Vogel admonished him and his classmates “to never romanticize the theater….There’s a battle out there. Think of yourselves as generals.“ Indeed, Vogel uses the military term “boot camp” to describe a specific approach to teaching. Two years ago she offered a free course in playwriting in New York City to 30 students – they signed up on a first come, first served basis –- to learn how to write a short play.

“A ‘boot camp’ can be taught during the week, or during a weekend,” Vogel explained. “But I also teach what I call a ‘bake off’ – a short play that everyone writes on the same theme. During my last ‘bake off’ in North Carolina, I gathered around 60 people in the room and told them they were going to write a short play that had a ghost, a statue, a master, a servant, sword play, and a scene of coitus interruptus. They had 48 hours to write it. No editing. No criticism. What happened was a room full of students bursting with tremendous energy.”

Paula Vogel. Photo: Carol Rosegg.

For Indecent, Vogel drew on her exposure to Yiddish as a youngster growing up in Washington, D.C., as well as on the experiences of director Rebecca Taichman, who encountered Yiddish through a relative in Canada.

“The Yiddish of Sholem Asch was not the High Yiddish of poet I.L. Pertez, or novelist Issac Bashevis Singer,” Vogel says. “It was the Yiddish spoken in the homes, in the factories, the Yiddish I heard at my grandmother’s knee when she told me words I wasn’t supposed to repeat in polite company.”

Indeed, this is the same Yiddish, or mama loshn (mother tongue), I heard spoken as a boy growing up among immigrant Jews who labored as “sweaters” in the schmatte (garment) shops in Providence, Rhode Island.

One of the first jobs playwright Asch had, Vogel recounted, was “writing letters for newly arrived immigrant Jews…he wanted to become a rabbi, but he ended up a playwright (and novelist) instead.”

One of the challenges that Vogel recalled she and Taichman faced with the play was finding a way to share their feeling about the Yiddish language with contemporary audiences. Yiddish was considered coarse by many, and it was considerably diminished when the Jews that spoke it were murdered by the Nazis during World War II.

“As a youngster, I grew up among people who experienced the Shoah (Holocaust), and who knew that the world would never be same,” Vogel said. “Yiddish is above all a language of yearning, a language of anxiety. I believe we’ve worked hard to communicate that love to audiences. We’ve had productions in Omaha, Nebraska and in Boise, Idaho, where Yiddish has rarely been spoken. Audiences there have said they feel the emotion we are trying to convey.”

Soon after the Boston run of Indecent, Vogel will be “guest teaching” at UCLA. She expects to return to Wellfleet in time to see the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown offer its first Women’s Playwrights Series. This new “workshop” series grew out of a challenge she presented to the FAWC board when she accepted an award from them in 2017.

“There is new leadership there now, “ Vogel said of the Center. “One of the great joys of my life is to make sure theater and the studying of theater is more accessible. And now that’s happening right here in my own backyard.”

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.