Dance Review: “Full on Forsythe” — Revolutionary

By Jessica Lockhart

William Forsythe asks dancers to go beyond their mastery of technique — in order to have the music move audiences to a higher level of emotional involvement.

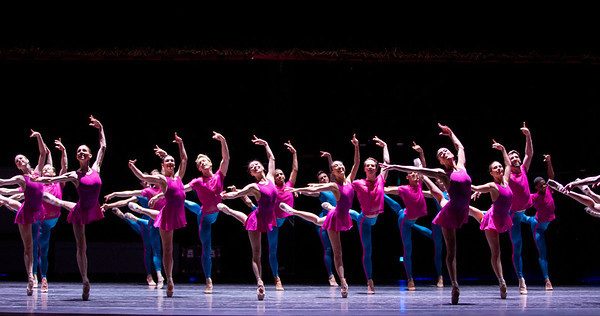

“Pas /Parts 2018” in the Boston Ballet presentation of “Full on Forsythe.” Photo: Rosalie O’Connor.

William Forsythe is considered to be one of ballet’s most groundbreaking choreographers. He has worked in Europe for the past 30 years. When he decided to return to the U.S., Forsythe established a partnership with Boston Ballet. He is currently half way through the arrangement; he is scheduled to create a total of five dances for the company. The three dances presented in Full on Forsythe (through March 17) concentrate our attention on the troupe’s dancers, and the ways that music can move them. Old fashioned? Yes, but it is still invigorating when modern music is employed. The evening’s dances don’t use videos, props, or spoken word, which are routine ingredients in multi-media enhancements, the kind that are designed to create a complex storytelling experience for contemporary audiences. All three dances are presented on a big open stage: the focus is only on the bodies and the sound.

“Playlist (EP)” was the finale, and it is a world premiere. This infectious dance juxtaposes classical ballet movement with popular songs in six parts. The piece opens with 12 male dancers scattered across the stage, swaying their hips to the music of singer Peven Everett. They are dressed in red t-shirts and blue athletic pants — a vision of real cool dudes! The dancing slowly becomes more intricate, including classical ballet movements, completed with grace and speed. Then the performers mix in bebop foot stomping and react to pulsing rhythms — as if they were out on a party dance floor. The piece was executed with passion as well as impressive skill.

The women displayed the same range of dynamics, dancing to the electronic funk of Abra, in another section of “Playlist (EP).” Their stretched arms and turning legs react to each beat and lyric. Forsythe has adapted the classical movement of ballet to contemporary music: what was rigid somehow becomes sinewy and lush. And memorably emotional: the dancing evokes the feeling that one receives from listening to a beloved song. Bodies become a means of suggesting the psychological resonance of the lyrics. The result is revolutionary, a new way of translating to the ballet the experience of hearing modern music.

A scene from Boston Ballet’s production of “Full on Forsythe.” Photo: Angela Sterling.

Part of what makes Forsythe’s strategy so effective is that it draws on contradiction. Highly skilled dancers are trained to hold the torso upright: it is liberating, artistically, when they are asked to bend in untraditional directions and manipulate their torso in unconventional ways. Ballet strives for a sense of weightlessness on pointe with effortless leaps and turns. Forsythe asks dancers to go beyond their mastery of technique — in order to have the music move audiences to a higher level of emotional involvement. The upshot is that the dancers are still precise but not rigid — they are actually playful. This high-spiritedness was in full throttle during the last segment, which was performed by the full company to Natalie Cole’s This Will Be (an everlasting love).

“Blake Works 1” created in 2016 for the Paris Opera Ballet features songs from 30 year-old British downtempo musician James Blake. His approach to composition ranges from electronic and soul to post-dubstep. A standout section in “Blake Works 1” featured a duet, performed to “The Color in Anything,” between principal dancers Chyrstyn Fentroy and Lasha Khozashvili. The haunting song’s drama was beautifully expressed through the couple’s struggle to embrace and detangle. The dancers wrapped their arms around each other in awkward gestures: each wanted to be held — but only for a moment. They kept pushing each other away. The attempt to embrace was messy, but they tried again and again. The feeling of desperately wanting the impossible was vividly conveyed –the dance is beautifully sad.

“Pas/Parts 2018” is a revision of a work that first premiered in 1999 at Paris Opera Ballet. The score, composed by Forsythe’s long time collaborator Thom Willems, is made up of electronically mixed sounds. The women’s costumes are two-toned: the front of the leotard is black, the rear a bold color. The geometric design is not only visually stunning; its power is enhanced by the exhilarating energy of the dancers, who moved with enormous force.

Jessica Lockhart is a National Endowment for the Arts Fellow in Dance Criticism and has a BA in Communication from the University of Southern Maine. Lockhart is a Maine Association of Broadcasters award winning independent journalist. Currently, she also works as program director at WMPG Community radio.