Book Interview: Tina Cassidy on the Woman Who Made Women’s Sufferage Happen

By Blake Maddux

Tina Cassidy talks about her revealing and enjoyable new book about how a woman’s right to vote became enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

Author and former Boston Globe journalist Tina Cassidy has covered quite a bit of historical acreage with the three books that she has written.

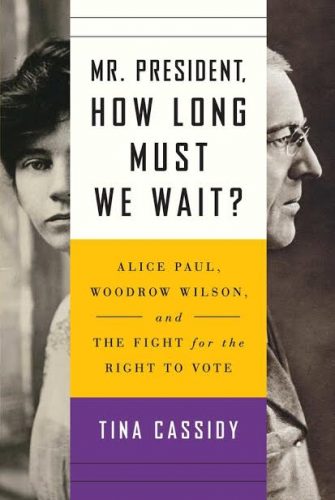

This is apparent by their titles: Birth: The Surprising History of How We Are Born (2006), Jackie After O: One Remarkable Year When Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Defied Expectations and Rediscovered Her Dreams (2012), and Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait?: Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote, which will be published by the Simon & Schuster imprint Atria Books on March 5.

Although the relatively obscure Paul is — in Cassidy’s words — the “clear protagonist,” How Long Must We Wait? is as thorough and insightful in its coverage of the much better-known Wilson. And while the book is not a military history, its chapters on World War I elucidate how the worldwide calamity obliterated the 28th president’s claim to have “kept us out of war” while providing a valuable opportunity for Paul and her fellow suffragists.

Cassidy will be discussing How Long Must We Wait? at Brookline Booksmith on the day of its release. She spoke by phone to The Arts Fuse about her revealing and enjoyable new book about how a woman’s right to vote became enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

The Arts Fuse: How is this book different from other books about the women’s suffrage movement?

Tina Cassidy: Well, I’ve read a lot of books about the suffrage movement and I’ve read a lot of biographies of Woodrow Wilson. The reason why I wrote this book is because I didn’t feel like there was a suffrage history that was narrative, that really expressed the drama of this tiny little Quaker from New Jersey, willing to take on the president of the United States, fully committed, for his entire two terms. So that was the story that really excited me here. These two very different people for the first time in a book, sharing the stage, if you will. All the biographies I’ve read of Wilson might have a sentence or a paragraph or maybe a few paragraphs about suffrage in it. That’s kind of shocking to me. This was one of the most important things that happened in the 20th century, and Wilson biographers tend to be more focused on his role in the League of Nations or other things.

AF: How much did you know about Alice Paul when you decided to write this book?

TC: I have to be honest and say that I knew nothing about Alice Paul. When I’m really interested in something that I know nothing about, it ends up being a book. It’s a great way to learn, frankly! But my curiosity about her and how the 19th Amendment passed is truly what inspired me here. She is not as well-known, I don’t believe, as Susan B. Anthony or even Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and yet she really picked up the baton from them and got the amendment passed. Frankly, the women’s suffrage movement was stalled, and not making any progress when Alice Paul came on the scene, and in fact, Susan B. Anthony was already dead. So this is the woman that made it happen and I think that that’s really interesting and also really sad that so few people actually know who she is. I don’t believe that she has been properly celebrated.

AF: Why do you think that is?

Author Tina Cassidy. Photo: Gulnara Niaz

TC: I think there’s two reasons why she’s not as well-known. One is that she was personally quite humble, and didn’t make the campaign for suffrage in any way about her. I also think that she was viewed as the sort of black sheep in the suffrage movement because she used more, I hesitate to use the word militant, but people describe it as such. She organized a suffrage parade, which today we would call a protest march. She organized the first protest outside of the White House, which was quite a radical thing then. So I think because of that, there are a lot of people who were grateful to have the vote but didn’t necessarily want to credit a radical with winning it.

And the other piece of it is that the president himself didn’t really recognize her contribution to it. That would have been admitting defeat. He praised another faction of the women’s movement, the women of the National American [Woman Suffrage Association], who went around asking for the vote at the state level. They were the polite ladies who were well-behaved.

AF: Should she be a household name like Susan B. Anthony?

TC: She should be a household name, because she was the singular person who demanded that a federal amendment was the only way that all American women would be enfranchised. The other suffragists were content keeping it at the state level. And there were a band of states that were never going to allow women to vote, so the federal amendment was really, in Alice Paul’s mind, the most egalitarian way to give more women the vote.

AF: How big of an influence on Paul was the time that she spent among the English suffragettes?

TC: It’s the reason why she became interested in suffrage. The suffragettes in England really showed her the way. They piqued her interest, they inspired her. She basically learned everything she knew from them and brought it home to America … I think learning the specific so-called militant tactics of the Pankhursts [English suffragettes Emmeline and Christabel] and bringing those home was exactly the gasoline to create the combustion in the women’s movement that was stuck. It was totally stalled before she brought these new ideas home.

AF: What was the significance of the timing of the United States’ entrance into World War I to the suffrage movement?

TC: World War I is important to this book for one really important reason, and that is because that war was about democracy in Europe. So it serves as a really tremendous backdrop for the suffragist movement in America because women were outraged that they were sending their husbands and sons to fight for democracy abroad and we did not have democracy at home. We were really kidding ourselves, right? And it was really a motivating factor, and it really created this stark contrast that I think helped the suffragist cause tremendously … How can we be the light for democracy around the world when we don’t even allow women to vote?

AF: Was there any sort of backlash when women began to actually avail themselves of access to the voting booth?

TC: I don’t believe that was a backlash, per se, but there was a lag that first year, in 1920, when women were allowed to vote. It was a fairly low turnout, and there were a couple of reasons why. One, they just didn’t have the muscle memory or the capability to know how to actually vote. That was going to require building up infrastructure and education and so forth. And it was 1920. There were still plenty of women who were quite conservative and were stuck in the mindset that there was one head of household and he was the one who made the decisions in politics and he spoke for the family. So it took time for that to change, but not too long. Within a decade, women were voting on par with men.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins–Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson–in Salem, Massachusetts.

Tagged: Alice Paul, Blake Maddux, How Long Must We Wait?, Tina Cassidy, women's vote