Classical Music Reviews: AEQUA, Philip Glass’s Symphony no. 11, and the Neave Trio plays Piazzolla

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Aequa is one of the year’s standout new-music albums. Philip Glass’s Symphony no. 11 suggests that the veteran composer has more than a few tricks left up his sleeve. And Neave Trio’s Celebrating Piazzolla is a thoroughly delightful, engaging album.

The music of Anna Thorvaldsdottir almost defies categorization. It is, on the one hand, rooted in tradition, thoughtfully structured, and marked by ideas that unfold with clear, inexorable logic. At the same time, it freely draws on styles and techniques that are very much of the present day. The influence of the natural world; sometimes a Messiaen-like sense of timelessness; and a free embrace of beautiful, consonant sonorities are also very much a part of Thorvaldsdottir’s voice.

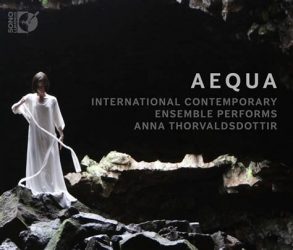

What does it all add up to? Well, for want of a more specific label, her music’s typically haunting and singular, traits that are powerfully demonstrated in her latest release, Aequa (Sono Luminus).

Aequilibria, a 2014 score for large chamber ensemble, is the disc’s biggest piece and exemplifies several of Thorvaldsdottir’s defining qualities. It opens with a series of busy, arpeggiated figures. These recur throughout its duration – indeed, they lead to its turbulent climax – but are countered (and sometimes accompanied) by long stretches of sustained, sonorous writing that suggests some kind of infinite sonic and psychological expanse.

Then there’s Spectra, a trio for violin, viola, and cello, which begins in a static place but, over its central third, becomes animated. After this involved middle section ends, the textures clear out and we’re left with a lovely melody that’s passed through the ensemble, anchored by sustained cello chords and punctuated by “seagull effect” glissandos. Gradually, these sounds, too, disintegrate into airy wisps.

Much of Thorvaldsdottir’s writing draws freely on extended techniques – breathing effects in the woodwind quartet Sequences, piano preparation in Scape, and so forth – but she never uses them as ends in themselves. Rather, they serve clear, expressive ends, as in Illumine, a delicately ravishing octet for strings, whose unaccompanied snap pizzicatos near the beginning foreshadow the seething last minute or so of the piece.

It’s compelling stuff, and the impeccable performances on offer – by Cory Smythe and members of the International Contemporary Ensemble (Steven Schick conducting) – make Aequa one of a year’s standout new-music album.

Philip Glass — he still has some musical tricks up his sleeve.

Love him or hate him, Philip Glass is, arguably, the most important symphonic composer of the 21st century. His Symphony no. 11 (Orange Mountain Music), which received its premiere at Carnegie Hall on his 80th birthday in January 2017, suggests Glass is a composer with more than a few tricks yet up his sleeve.

The first movement, for example, is structured in big rhetorical musical paragraphs and owes a big spiritual and technical debt to Bruckner – even as it draws on earlier pieces of Glass’s.

Subtle metrical games unfold in the big middle movement, which isn’t exactly a slow movement: it starts and ends spaciously, but the big, central part is marked by roiling arpeggios and pungent shifts of harmony that accompany long-breathed-but-urgent lyrical episodes.

It’s in the Eleventh’s finale, though, that the music really heads in some strange, unexpected directions. An extended percussion introduction is eventually joined by a tune that almost sounds like a John Adams reinvention of an Ives march before more typically Glass-ian figures try to emerge. Nothing quite settles down, though, and, before long, the whole thing’s transformed into a phantasmagoric romp. Fragments of melodies, percussive riffs, and a sort of gleeful, anything-goes mentality prevails to the riotous final bars. Surely, this is one of the most unpredictable movements Glass has ever written.

The performance by the Bruckner Orchester Linz and Dennis Russell Davies brims with spirit and color. This is an ensemble that knows Glass’s symphonic output better than anybody (they premiered all but one of his symphonies) and they’re totally at home in his style. Here, that means the orchestra can emphasize the music’s subtle details – the harp arpeggios in the second movement, the xylophone accompaniment to one of the finale’s opening tunes, etc. – with a real sense of character and purpose, but never lose sight of where the larger piece is heading. And they know a thing or two about how to effectively pace Glass’s large-scale forms. In all, then, a rousing accomplishment.

If you heard the Neave Trio’s French Moments album from earlier this year (Arts Fuse review), it should come as no surprise that the ensemble plays with character and panache. How well their approach translates to the passionate world of the Argentine tango, though, may come as a bit of a shock…as in, you might be astonished that they didn’t get their collective start in one of Astor Piazzolla’s quintets. At least that’s one takeaway from Celebrating Piazzolla, the group’s first release on the Azica label.

The Neave’s make fiery work of José Bragato’s arrangement of Piazzolla’s Las cuatro estaciones porteñas, a set of four “portraits” of Buenos Aires that correspond to each of the year’s season. “Primavera Porteña,” with its biting rhythms and slashing accents, draws torrid playing from violinist Anna Williams, in particular. The second movement, “Verano Porteño,” receives a swooning, sultry reading from the group, while cellist Mikhail Veselov makes scorching work of his solos in “Otoño Porteño.” A glowing nostalgia informs the lush finale, “Invierno Porteño.”

Vocalist Carla Jablonski then joins the Neaves for a set of five Piazzolla songs, all in arrangements by Leonardo Suárez Paz.

Jablonski brings rich tone and knowing heat to “Los pájaros perdidos,” a 1973 canto that channels Weill almost as much it does Piazzolla. In “El Gordo Triste” and “El Titere,” her spot-on intonation, tight rhythms, and dusky register imbue Piazzolla’s Cimmerian writing with force and direction. A similar focus marks her performances of “Oblivion” and “Yo soy Maria,” the latter a tango song from Piazzolla’s 1968 operetta Maria de Buenos Aires.

The album’s last track, “Milonga de los Monsters” isn’t a Piazzolla creation – it’s by Suárez Paz – but, in terms of language and style, it’s a loving homage to the older composer. Williams makes blistering work of the opening violin cadenza, while cellist Veselov, pianist Eri Nakamura, and Jablonski play (and sing) with droll energy. A fresh, spirited ending, then, to a thoroughly delightful, engaging album.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.