Visual Arts Review: Surrealism — One of America’s Favorite Art “isms”

By Peter Walsh

Despite its serious treatment of surreal art, Monsters & Myths is a real delight.

Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s at The Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford, CT, through January 13, 2019.

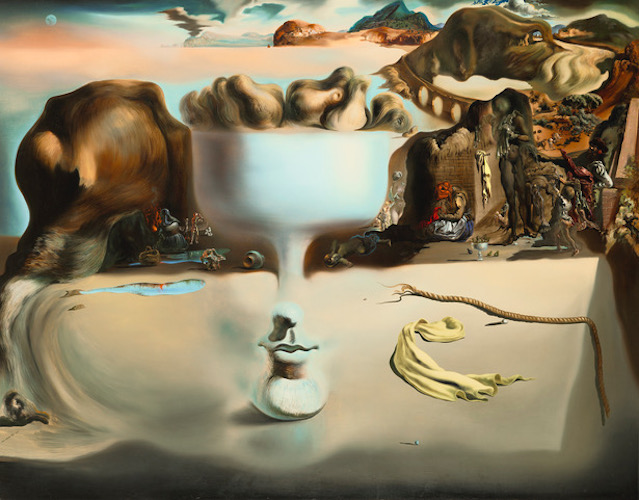

Salvador Dali, “Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach,” 1938. Oil on canvas, 45 x 56 5/8 in. Photo: courtesy of the Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art.

Of all the many “isms” of 20th-century art, Surrealism, in America, is surely the biggest hit. Analytic Cubism might confuse and Abstract Expressionism annoy but Surrealism, enigmatic but not opaque, with its easy-to-read photographic illusionism, dream-like images, visual puns and puzzles, playful jests, flamboyant theatricality, strange juxtapositions of the ordinary and the bizarre, and Freudian edginess appeals to an American idea of what advanced art and artists should be. Surrealism, a movement founded by artist and writers with revolutionary intent and distinct leftist overtones, became immensely popular on this side of the Atlantic almost as soon as it arrived. It has remained so ever since.

Its success was, in fact, stunning. New York department stores hired Surrealists to arrange shop windows. Fashion houses enlisted them to design clothes and photograph models. Hollywood directors eagerly collaborated with them. Pop icons wrote songs about them. Their influence on graphic design and advertising seems limitless. And the catchphrase “It’s so surreal” has entered the language as a code for bemused angst.

The Wadsworth Athenaeum’s fascinating surrealism exhibition was jointly organized by two American museums, the Wadsworth and the Baltimore Museum of Art, with important collections of Surrealist art. It is focused (with some digressions) on Surrealism and the war years, when many European modern artists were in exile in the U.S, But woven into the tapestry are many other narratives: the Surrealists’ early and vehement resistance to European fascism, the rich history of Surrealism in Hartford and Connecticut, harrowing tales of artists driven out of country to country by war and repression, the reception of advanced modern art by American collectors and museums, the many overlapping relationships and influences between artists, gallery owners, collectors, museum curators, and each other. Finally, a suggestion of a coda: the early, surrealist careers of American artists who went on to found Abstract Expressionism.

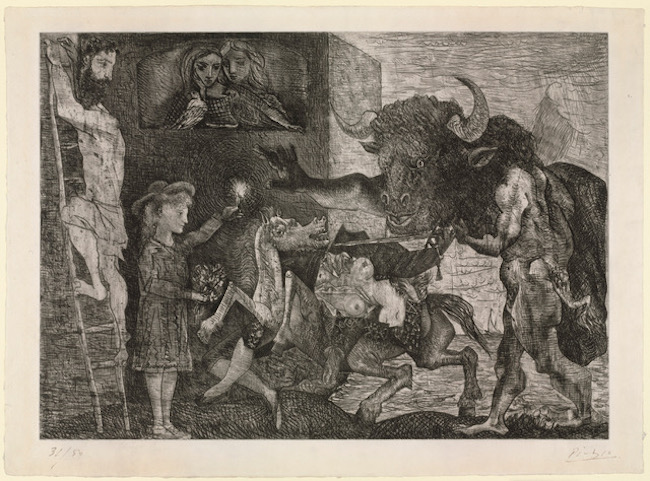

Monsters and Myths is built around a series of key work that include Salvadore Dali’s “Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach,”1938, and “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War),” 1936; Max Ernst’s “Europe After the Rain II,” 1940-42; Pablo Picasso’s etching “Minotauromachy,” 1935; André Masson’s “There Is No Finished World,” 1942; and Joan Miro’s “A Drop of Dew Falling from the Wing of a Bird Awakens Rosalie Asleep in the Shade of a Cobweb,” 1939. The “monsters and myths” of the show’s title spans figures from classical myths, including the half-man, half-bull Minotaur, and figures from imaginary and real nightmares, especially the Dictator Francisco Franco, whose destruction, in the 1930s, with the help of Hitler and Mussolini, of the Spanish Republic is a particular fixation of the Spanish artists in the show. There is also a rich selection of the full range of Surrealist preoccupations, including a number of artists little known today.

Pablo Picasso, “Minotauromachy,” 1935. Etching on cream laid paper. The Baltimore Museum of Art Gift of Israel and Selma Rosen, Baltimore (BMA 1979.72). © 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The Wadsworth’s large Dali canvas, “Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish,” sums up much of the show’s content. In this feverishly ambiguous, austere landscape of sand and mountains, the viewer can resolve a dog, a bowl of a fruit, and a human face. The face is that of the great Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. Lorca had been arrested in his native Granada in 1936, never to be seen again. It was widely believed he had been assassinated by a right-wing militia, considered by many to be one of the great atrocities of the Spanish Civil War.

Ernst’s “Europe After the Rain,” is typical of another type of Surrealist landscape: bleak, desert-like, and thinly populated with distorted figures, creatures, or geological formations. On this canvas, completed shortly after the artist fled captivity in Europe for the United States, Ernst creates what seems to be a premonition of the devastated post-war cities of Europe, filled with images borrowed from Medieval visions of Hell and crusted over with what could be coral or melted masonry.

Several times the exhibition moves out of the strict time frame of its title. René Magritte’s “The Fickleness of the Heart” was painted years after the end of the war in 1950. Given to the Wadsworth by two giants of American dance, ballet master and choreographer George Balanchine and his fourth wife, dancer Tanaquil LeClercq, it only hints at a violence that could be either physical or psychological. The painting shows the deadpan technique and unsettling juxtaposition of spare spaces and ordinary objects that have made Magritte one of the most beloved of the Surrealists.

Georgio De Chirico’s “The Endless Voyage,” also in the Wadsworth collection, was painted in 1914, long before there was such a thing as Surrealism. Its presence suggests the tempestuous relationship between the Italian painter the true Surrealists. Discovered in 1920s Paris by the poet André Breton, co-founder of the Surrealist movement and author of its manifestos, De Chirico’s pre-War “Metaphysical” paintings had a profound influence on the Surrealists, even though by then De Chirico had moved on to a traditionalist, classical style that they detested. Nevertheless, De Chirico’s Surrealist admirers admitted them into their group until growing aesthetic differences drove them apart. De Chirico, content to live in Fascist Italy and increasingly at odds with the whole of modern art, later denounced his former admirers as “contentious and hostile.” By the 1930s, he was painting in a neo-Baroque style inspired by Rubens.

A side gallery gathers together documents that connect the Wadsworth and many figures, European and American, connected to the Surrealist Movement. Under the legendary directorship of the Wadsworth by A. Everett “Chick” Austin, from 1927 to 1944, the museum was one of the most progressive and innovative in America, collecting advanced modern art even before New York’s Museum of Modern Art had been established. Several important Surrealists settled in Connecticut or had ties there. Masson moved to the village of New Preston, not far from Alexander Calder’s in Roxbury. Dalì visited Hartford in the 1930s. Yves Tanguy and his American wife, Surrealist painter and poet Kay Sage, settled permanently in Woodbury where they remained for the rest of their lives. After taking up residence in New York, Breton organized a major Surrealist exhibition at Yale.

By the exhibition’s account, Hartford society and even its local mass-market newspapers embraced the movement. The gallery documents Surrealist events and parties and the network of artists, curators, collectors, art dealers, and scholars that connected New York City, Hartford, and nearby universities and towns.

The influx of European artists during the war years had a major influence on the relatively provincial American art community. Previously, American artists had known their work largely through imported publications. Now European artists were living almost next door; their paintings and sculpture were there to be seen in galleries, museums, studios, and private homes.

Joan Miró, “A Drop of Dew Falling from the Wing of a Bird Awakens Rosalie Asleep in the Shade of a Cobweb,’ 1939, Oil on basketweave fabric. University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City, Purchase, Mark Ranney Memorial Fund (1948.3). © Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris 2018.

One of the most interesting themes of the Wadsworth exhibition is the Surrealist phase of young American artists who went on to become major figures in world art in the 1950s and ‘60s. David Smith’s bitterly anti-war “Medals for Dishonor,” massive dinner-plate-sized cast bronzes from the late ‘30s are among the sculptor’s most ambitious early works. Suggesting commemorative bronzes that were popular at the time, the “medals” use a classic vocabulary of Surrealist imagery to “award” scientific warfare, collaboration of the clergy, propaganda, and other horrors of modern warfare. Mark Rothko’s “The Syrian Bull,” 1943, and Jackson Pollock’s “Water Birds,” 1943, show how deep the the Surrealist influence ran in this younger generation of Americans. Both artists use adapted Surrealist imagery while edging ever so slightly towards abstraction.

It was as if Smith, Rothko, Pollock, and other younger Americans grew out of their Surrealist phases as they matured as artists. The rough and tumble, post-War, and thoroughly American Abstract Expressionist movement digested all European influences completely. In due time, that “ism” came to overthrow Europe’s dominance in world art. This early American Surrealist work comes across now as a youthful phase that the Expressionists later outgrew.

Something similar eventually happened in the critical reception of Surrealism. While the more restrained Surrealists like Miro and Magritte ascended to Modern Master status, the reputations of the flamboyant Dalì and Ernst in particular, declined. A few cast them in with the poseurs of modern art. Some specialists regret Picasso’s “diversion” into Surrealist imagery, even though it produced his great anti-war masterpiece, “Guernica.”

None of this insider debate need particularly concern visitors. Despite its serious theme, Monsters & Myths is a real delight.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than eighty projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Tagged: Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s, peter-Walsh, surrealism