Book Review: “In the Galway Silence” — Another Tour of Hell

By Lucas Spiro

Jack Taylor’s world is very much our world and his despair is our despair.

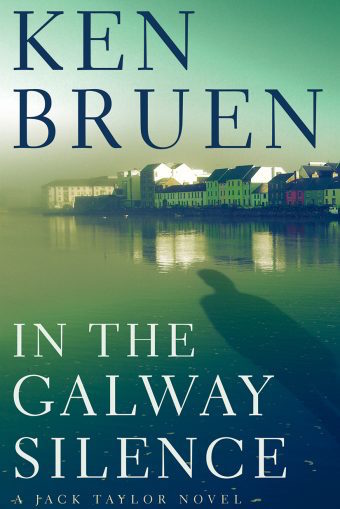

In the Galway Silence by Ken Bruen. Grove Atlantic, The Mysterious Press, 320 pages, $26.

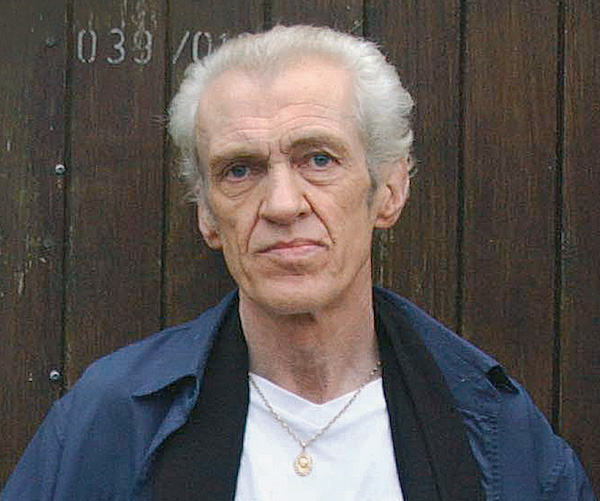

Jack Taylor cannot be happy. He says so himself, right there in chapter one of In the Galway Silence, the latest gruesome installment in the sordid life of Ken Bruen’s ex-cop anti-hero. “I was happy,” he says. Past tense. Anyone familiar with Bruen’s cruel style knows that happiness for Taylor is usually a bad omen, a surefire generator of future suffering. Bruen is regarded as one of Ireland’s premier noir writers, the “Godfather of the modern Irish crime novel,” and the reasons is that his stories relentlessly depict a person who seems to literally live in Hell. Satisfaction, joy, fulfillment, these only multiply the intensity of the psychological and physical violence that awaits Jack in a Galway that acts as a microcosm of everything that is bad in our world. And it appears that all the world’s misery finds its way into the world through Jack’s bedraggled heart.

Jack “had endured just about every trauma there is and had reached the point of suicide, and then,

Things got worse.” Bruen’s brusque language and signature line breaks are used to throttle the reader throughout this nearly impenetrable narrative. The book’s prose, like Jack himself, serves up a series of isolated objects, things, and ambiguous feelings. The thing is approached but never penetrated; vital information remains hidden in the shadows. Bruen is no stranger to the philosophical (he has a doctorate in metaphysics) and his absurdly grotesque and violent version of Galway, like Dante’s Inferno, is the perfect place to explore existential woe in a morally bankrupt social order. In Jack, we are served up the ceaseless torture of someone who just can’t seem to die, as much as he invites Death.

That there is no “end game” for Jack as he maneuvers through the maddeningly arbitrary narrative structure, over which Bruen overlays a chess motif. The catch is that it seems to be a chess match watched by someone who doesn’t understand how the pieces move. Jack gets tangled up in a murder spree that a wealthy banker (never a good dude in a Jack Taylor novel) named Jean Renaud unleashes on the city in the form of a ‘knight.” An American killer who is driven by a psychopathic code along with an obsession with chess. He goes by the moniker The Silence. Why does The Silence kill? That’s like asking why the horsey moves in an L. Because it’s the horsey.

However, Jack is given an out early on in the novel. His new girlfriend asks him to come to America for a month with her. Jack declines. He has been approached by the wealthy banker, who’s eighteen-year-old twin sons have been murdered by The Silence. He drowned them in the river after tying them to a wheelchair and supergluing their mouths shut.

Why doesn’t Jack go with his new belle? Because he’s Jack. He begins “a low-key investigation into the deaths,” which is like a junkie or a drunk (Jack is both) saying they’ll “just have one.” Contemporary narratives are full of these kinds of characters — the emotionally crippled anti-hero who can’t stop himself from continuing to mess up his life. And that is trying for some readers, understandably. But this is crime fiction: Jack can’t change too much, otherwise the novel might become “literary,” which is the last kind of book Jack wants to be in. Bruen masterfully moves the pieces, throwing Jack continually into the fray, a pawn who must battle kings, queens, knights, and bishops in the forms of bankers, ex-wives, corrupt cops, and, well, bishops. All of this in an Ireland still hurting from the recent complete economic collapse at the hands of a few greedy financiers and politicians.

The Emerald Noir style, as Paul French recently observed in CrimeReads, is deeply “concerned with contemporary Ireland,” an interest in contemporary decay that might be one of the reasons for the genre’s popularity. Jack Taylor, for all his selfish, self-pitying, and self-destructive behavior, is perpetually distressed by what he reads in the newspapers; he consumes tons of media through Netflix and DVD boxsets. Reading a Jack Taylor novel is like getting a digest of the previous year’s awful headlines. When he is first approached by Renaud, Jack is “Reading the latest horror from Trump. Le Pen was ranting in France and all of Europe in turmoil.” Jack’s world is very much our world and his despair is our despair.

Ken Bruen — Godfather of the modern Irish crime novel. Photo: Grove Atlantic

There’s an element to Jack’s character that is a little perplexing. The clichés — the whiskey, the fighting, the references to his media tastes — are traditional genre stuff. But then he cuts against type in ways that might be confusing. He doesn’t like the new, the hip, the different. He meets his girlfriend and her son at a restaurant he likes a lot because “they still served old-fashioned grub and had no list of calories on the menu.” This is the first time he’s meeting the son, who has “a curled lip, from attitude rather than design.” The kid complains about not being able to go to McDonald’s: symbolic of a cheapening culture driven by the expansion of US hegemony, poisonous food that comes with a calorie count. By the end of Jack’s first meeting with the kid he’s berating the man for being exactly who he is — unwilling to change, confused about the horrors around him, and with no way to make the ghosts of his past go away. His psychological makeup would seem to make him an ideal recruit by Trumpian forces. And yet, for all his insensitivities, Jack’s no reactionary. He just doesn’t know how else to be, how else to move around the board — other than how the chess master has made him. It’s the only way he knows how to survive, but even that doesn’t always seem worth it.

In the Galway Silence has some quietly illuminating moments. It’s hard to slow down when reading a Bruen novel, but it pays not to rifle through — give it a patient perusal. He begins each chapter with a quotation, asking us to pause and consider its meaning before turning the page. They come from very different sources in Bruen’s universe of admired voices, from Edgar Allan Poe to Mother Theresa:

“The Irish can abide anything save silence.”

“The true genius shudders at incompleteness and usually prefers silence to saying something which is not everything it should be.”

“We need silence to be able to touch souls.”

“If you go far enough into the past you will meet yourself coming back (Galway drinking song lyric).”

And, “To appreciate silence you kind of need first to shut the fuck up.”

Good advice.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.