Classical Music Review: “Widma” — An Imaginative Polish Experiment

By Ralph P. Locke

This recording challenges our settled sense of what art music, in conjunction with colorful spoken and sung verse, can accomplish.

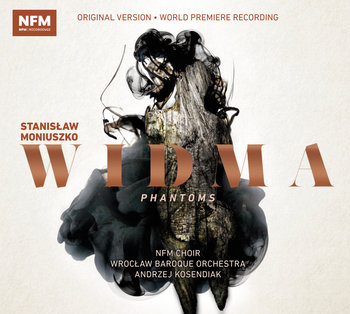

Stanisław Moniuszko’s Widma (cantata) NFM CDAccordACD243 — 65 minutes

Aleksandra Kubas-Kruk, soprano; Jaroslaw Bręk, Jerzy Butryn, Bogdan Makal, bass-baritones; Antoni and Mikołaj Szuszkiewicz, boy soprano, Wroclaw Baroque Orchestra, NFM Choir, conducted by Andrzej Kosendiak.

According to the fascinating booklet that comes with this world-premiere recording of Widma (Phantoms, 1865), the noted Polish composer Stanislaw Moniuszko (1819-72) — known outside of Poland mainly for one opera, Halka — was inspired to write several cantatas after encountering Félicien David’s Le désert (The Desert), the “ode-symphony” of 1844 that had taken the musical world by storm. (David’s remarkably fresh work has now been recorded twice, and quite enchantingly. See my review here. Moniuszko would eventually conduct Le désert in Warsaw. David’s other “ode-symphony,” Christophe Colomb, has been recorded recently as well.)

According to the fascinating booklet that comes with this world-premiere recording of Widma (Phantoms, 1865), the noted Polish composer Stanislaw Moniuszko (1819-72) — known outside of Poland mainly for one opera, Halka — was inspired to write several cantatas after encountering Félicien David’s Le désert (The Desert), the “ode-symphony” of 1844 that had taken the musical world by storm. (David’s remarkably fresh work has now been recorded twice, and quite enchantingly. See my review here. Moniuszko would eventually conduct Le désert in Warsaw. David’s other “ode-symphony,” Christophe Colomb, has been recorded recently as well.)

Whereas Le désert portrays a caravan wending its weary, determined way across the vast sands of some Arab land, Moniuszko’s Widma cantata deals with village life, class conflict, young love, death, and moral and religious values in a strictly Polish (indeed, often specifically Polish-Catholic) context. Nonetheless, there is a striking resemblance between the two works: both combine spoken poetry, solo vocal numbers, choral sections, and purely orchestral passages.

The texts in Widma are excerpted from part 2 of a major verse epic, Dziady (Forefathers’ Eve), by Poland’s most renowned poet, Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855). Forefathers’ Eve, as Mickiewicz explains, is an Eastern European custom — pagan in origin, but with some Christian coloration because of its having been linked up to All Soul’s Day — in which the souls of one’s progenitors and of individuals still in Purgatory are summoned up. As in Dvořák’s cantata The Specter’s Bride — which uses all the elements mentioned in the previous paragraph except spoken recitation — the solo singers represent the poem’s various characters. In this case, there are eight: Guślarz (a figure melding traits of a pagan bard and, here, a Catholic priest), a Maiden, a Ghost or Phantom, a Voice, an Old Man, an Owl, a Raven, and a Little Angel (sung here by two boy sopranos). The characters also are assigned verses that are to be recited rather than sung. On this recording, the reciting is done by brilliant actors capable of conveying a wide range of emotions. (In the header I have not named the actors, nor two minor singers.)

Mickiewicz’s verses mingle a wide range of mythical, religious, anti-aristocratic, and nationalistic images, and include such lines as: “He who’s not tasted bitterness / Will take no sweets from Jesus’ hand” and (sung by the ghost of a feudal lord who was vicious during his life) “My body’s ever slit and rent: / [Serving now as] ravenous vultures’ filthy meat.” To the latter, the chorus of ravens eventually replies in one of the work’s most intense passages: “Tear up each morsel, rip each piece– / And when there’s no more bread or wine / Slice off his flesh! Let bare bones shine.”

The alternation between spoken poetry and sung-and-orchestral music provides continual contrast that kept me quite curious about what the poet and the composer would do next. This unpredictability was further enhanced by an oddity in the booklet text: no clue is given about which passages are spoken and which are sung! More generally, the work offers occasion for reflecting on the different ways in which poetry can be conveyed and reinforced by voices (speaking, singing) and by instruments.

Moniuszko’s style in this work is intensely communicative, sometimes dark and foreboding (one recurring passage recalls the Wolf’s Glen scene in Der Freischütz), other times gentle and bouncing, as in the barcarolle-style duet for Guślarz and the Maiden — with choral support- — describing the Maiden’s light step as she wanders the countryside amidst butterflies and lambs. The Maiden also gets a short, waltzlike song to sing, at which point we learn her name: Zosia. We also end up learning that she died at nineteen. Happiness and painful loss are ever entwined in this fascinating work.

The performance is extremely strong. If you ever get a chance to hear any of the four adult singers named above, grab it! (The two boys are good, too.) The five reciters often speak quietly and confidentially, trusting in the microphone to amplify their gentle sounds. Early on, I found myself wishing that they would put more oomph into the task. I figured that this would have made the whole experience sound more consistently concert-like, whereas it often shifts between a full-bodied concert acoustic and the intimacy of a radio drama.

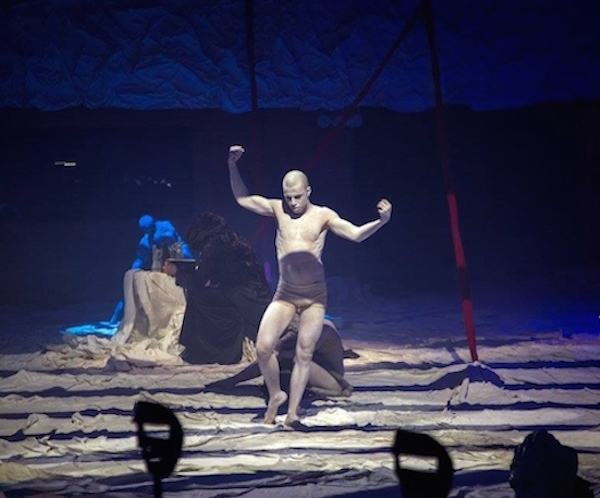

A scene from a recent Polish production in Warsaw’s Teatr Powszechny of “Widma.” Photo: Joanna Stoga/NFM.

Also (I was beginning to feel), a similar full-throated delivery would have helped the speaker and singer of the same role sound more similar. Two other performances of this work can be heard, in full or in excerpts, on YouTube. Both have the singer also do his or her character’s spoken lines; this helps me feel involved, as I watch and listen, even though the performances are in other ways much less expert than on this CD. The performances are also semi-staged, with simple costumes (or, in one case, with highly proficient modern dancers).

But back to the CD! As the drama increased, the reciters — who had first seemed too tame — became more spirited and varied in their delivery –indeed, sometimes downright grotesque and scary. In short, many wise aesthetic decisions have been made here; what I at first took to be a flaw is no flaw at all.

I recommend this recording for listening pleasure and also as a challenge to one’s settled sense of what art music, in conjunction with colorful spoken and sung verse, can accomplish.

The poetic texts are very helpfully laid out — not least by distinguishing between Mickiewicz’s original wordings and certain adaptations made by the composer. The English translations of the verses are the skillful work of the noted Slavicist Charles Kraszewski.

All in all, Widma reveals many aspects of Polish national and religious culture that one rarely encounters in international musical and cultural life. One essay in the booklet helpfully explains the scholarly effort that went into restoring the composer’s original intentions in this recording. The other essay regrets that Poland seems fated to have Moniuszko “all to ourselves. And only to ourselves.” Widma, now that we can get to know it, may well help draw wider attention to this composer’s imaginative compositional experiments.

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book.

Tagged: cantata, NFM Choir, Ralph P. Locke, Stanislaw Moniuszko, Widma