Poetry Review: Poems, Not Artifacts — “New Poets of Native Nations” and a “Poets Playlist” at the Peabody

Editor Heidi E. Erdrich has brought together a richly varied selection of poems, chosen from first collections of poetry written by twenty-one Native poets since the year 2000.

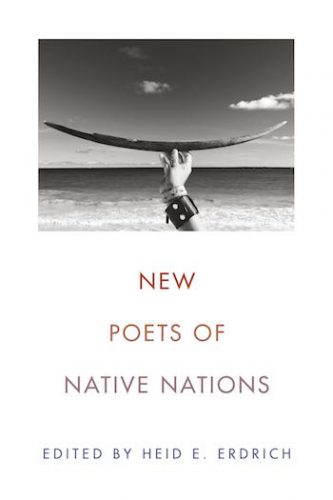

New Poets of Native Nations, edited by Heid E. Erdrich. Greywolf Press, 304 pages, $18.

Native American Poets Playlist: Poets in the Gallery, Harvard Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, through November 30.

By Eric Fishman

In one of his poems in this collection, Tommy Pico describes listening to the unfortunate conversation of two “white ladies in buttery shawls” as they wander past a display case of “traditional” Native clothing in a natural history museum.

It’s horrible how their culture was destroyed

as if in some reckless storm

but thank god we were able to save some of these artifacts – history is so

important. Will you look at this metalwork? I could cry —

I listened to a recording of Pico read this poem as I myself — a white man without a shawl — wandered past a similar display case in the Peabody Museum of Natural History. The poem is part of a “playlist” of eight poems from the New Poets of Native Nations collection that you can carry on an audio player as you walk around the exhibits. It’s a strange thing to encounter poetry in a museum of archaeology and ethnology, instead of in an art museum. Are these poems another example of Native cultures being put on display for others to observe?

The difference is that objects cannot talk back to you like poems. And poems like Pico’s can bring museum goers to reflect on their own biases regarding how they relate to the “historical artifacts” in museums. Voices cannot be so easily exiled to the past. Earlier in this poem, Pico asserts that “I don’t want to be seen, generally.” But listening to the recording of his reading, the comma disappears: “I don’t want to be seen generally.” This feels a natural epigraph for this anthology and exhibit.

Anthologies can be agents either of generalization – “this is what Native poetry is” – or granularization – “this … and this … and this … are what Native poetry can be.” This anthology falls into the second group. Heid E. Erdrich, the editor, has brought together a richly varied selection of poems, chosen from first collections of poetry written by twenty-one Native poets since the year 2000. As Erdrich stresses in her introduction: “Our poetry might be hundreds of distinct tribal and cultural poetics as well as American poetry.” This collection gives a glimpse into some of these many complex artistic identities.

I want to be mindful of the dangers presented in being a White critic writing about Native literature. Gordon Henry, Jr. warns, in “Simple Four Part Directions for Making Indian Lit”:

read to:

They may be hearing

Indin in everything

non Indin

Perhaps it is telling that the first thing I did when contemplating this review was to ask around for recommendations of essay collections about Native poetry. The critic’s drive to set literature into frameworks comes from an impulse to contextualize — to help the reader see how a small segment might fit into larger patterns — but also from a temptation towards intellectualization, and away from lived experience. This intellectual bent is itself part of a larger pattern of academics (and particularly, white academics) describing Native cultures, and thus relegating them to the museum case of the other. As Erdrich notes: “It is often said that we original inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere are the most written about peoples on earth. But our own writing is often ignored or placed in restrictive contexts that keep us in the past and far from the words contemporary or new.” Erdrich’s stated goal, then, is to help move Native writing away from the realm of “artifacts” and towards the realm of, well, writing.

“Everything is in the language we use,” writes Layli Long Soldier, in “38.” She is referring to the treaties the US Government amended and broke repeatedly with the Dakota people. However, one of the ways the poets in this volume complicate this statement is through the use of Native languages. Margaret Noodin, of Chippewa heritage, tells us in the author notes that:

Akawe nind’anishinaabegiige apane. I always write first in Anishinaabemowin.

Indeed, we encounter her poems first in Anishinaabemowin, on the left-hand column, with her translations into English on the right. This is a radical gesture, a staking out of territory. Anishinaabemowin is reinstalled as the primary language of the poem, and English as a latecomer, one who must strive towards the original. Brandy Nālani McDougall, in explaining her refusal to italicize ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i when she uses it in her poems, observes wryly that:

to adhere to the MLA rules of italicizing foreign languages means that all of the English should be italicized and all of the Indigenous American and Pacific languages left “Roman.”

The use of these languages in a political decision. Yet it is also a personal one. For the poet, the calling forth of heritage languages can be a way to connect to past — and future — generations. In “The Petroglyphs at Olowalu,” McDougall writes:

their words I ask for, the old work of hands.

In many communities, the use of Native languages still carries significant intergenerational trauma, trauma that originated from residential boarding schools where teachers would throw students in “black / isolation chambers for speaking / a language still their only ink” (Eric Gansworth, “It Goes Something Like This”). Several of the poets, in their author notes, discuss how they use these languages as a conduit towards learning cultural practices they didn’t learn as children. Trevino L. Brings Plenty tells us that, “I come to use Lakota words as I gather momentum learning my language and cultural practices.” Just as each poet writes with their own form of English, one that feels necessary to express their inner world, poets can use their heritage languages to express thoughts they could not otherwise. Dg nanouk okpik writes that “I can use Inupiaq as a tool to be as concise in the Inupiaq thought process.” Languages die unless they are used, and not only used, but welcomed into the most intimate spaces of the peoples’ bodies and minds. Perhaps writing poetry is one way for these languages, and those who speak them, to “rise up and be renewed” (Noodin).

The use of languages other than English in poems, when they aren’t translated, can feel estranging for a non-Native reader. And this is perhaps part of the point. At a reading at the Peabody given by Erdrich, Gansworth, and Tacey M. Atsitty, a White audience member asked how they should engage with moments of polylingualism in the poems. The panelists offered different perspectives. One suggested that “maybe you take it as music.” Another suggested an aesthetic approach, to “notice the lines’ shape on the page.” The most provocative response, though was political: “why shouldn’t the reader experience the feeling of being dominated by another language?” This is one of the ways the poems in this volume resist complete understanding, resist “mastery” and the ownership it implies.

Of course, for many of these poets, English is their first and their primary language of thought and writing. Yet the use of multiple languages offers a potent allegory for the larger mission of this volume: to move Native poetry out of the realm of tokens and artifacts. Writing in a language other than English is one way to hold something back from the reader. Layli Long Soldier insists that “everything is in the language we use.” Yet we don’t all have access to these languages. This is one of the most compelling reasons I can think of to read: to experience something you cannot fully grasp. “I show you my poem,” the poets seem to be saying, “but I keep something behind, something you do not have the key to enter.”

Eric Fishman is an elementary school teacher, writer, translator, and cellist. His Water Slower than Stones: Poems of André du Bouchet, co-translated with Hoyt Rogers, is forthcoming from Bitter Oleander Press. For more information, visit here.