The Arts on Stamps of the World — November 6

An Arts Fuse regular feature returns (temporarily): The Arts on Stamps of the World.

By Doug Briscoe

With a post intended for last November 6th we come to the final entry in our project to restore to fullness the grand spectrum that was The Arts on Stamps of the World. A word of caution: don’t become so engrossed in the scintillating subject matter that you forget to vote!

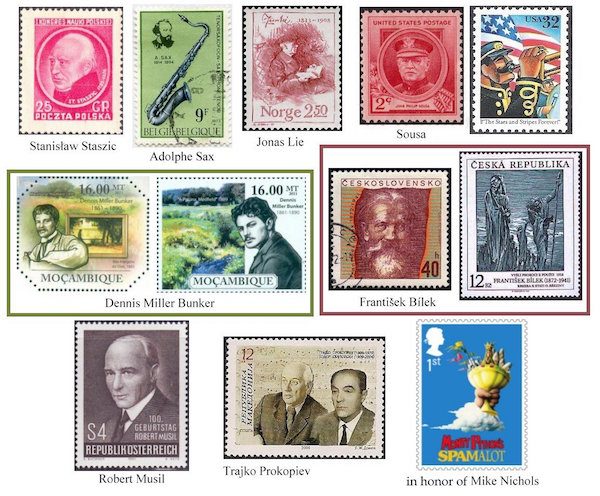

November 6th’s most prominent figures are John Philip Sousa, Robert Musil, Mike Nichols, and the inventor of the saxophone. (No, there’s no Mike Nichols stamp, but there is one for Spamalot!)

Polish polymath—or perhaps I should call him a Polishmath—Stanisław Staszic (stah-NEE-swahf STAH-shits, by your leave) was an extremely important figure in the Enlightenment in his country. He helped establish the Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning in 1800 and became its president in 1808, retaining the position until his death. Staszic, who was baptized on this day in 1755 and died on 20 January 1826, was of greater significance as a statesman, political thinker, philosopher, geologist, statistical analyst, sociologist, ethnographer, student of mining, industry, and the Tatra Mountains, and writer on a number of these topics than as a poet. But as he did compose at least one work in poetic form, he earns a place here on AoSotW. The book in question is Humankind: A Didactic Poem (Ród Ludzki. Poema Dydaktyczne), a huge, three-volume philosophical essay and poem. (I gather the entire thing was written in verse.) Another reason to include Staszic here is that he translated the Iliad into Polish in 1811, although that effort was not well regarded. Curiously enough, it was precisely one hundred years later that Poland issued this stamp for him as part of a set recognizing the First Congress of Polish Science. By the way, Staszic was also a Catholic priest and abolitionist (of serfdom). Another thing: Charles Dickens wrote a novella, “Judge Not”, with Staszic as the main character in 1851!

Belgian Antoine-Joseph “Adolphe” Sax (1814 – c. 7 February 1894) invented the saxophone (as well as the saxotromba, the saxhorn, and the saxtuba!). The saxophone was patented in 1846, though Berlioz had admired it as early as 1842. Sax’s parents were also instrument makers, and Adolf himself entered two of his own flutes and a clarinet into a competition when he was just 15. His childhood was an incredible litany of accidental, near-fatal injuries: he fell from a three-story window, drank a bowl of vitriolized water, was burned in a gunpowder explosion, fell onto a hot frying pan, fell into a river and was nearly drowned… His neighbors called him “little Sax, the ghost”.

Though much less well known outside Norway, Jonas Lie (pronounced YO-nahs LEE-eh, with just a hint of a second syllable in the surname; 6 November 1833 – 5 July 1908) is held by his countrymen to belong in the company of Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. With Alexander Kielland, another name most of us wouldn’t recognize, Lie is one of the Four Greats of 19th century Norwegian literature. From the ages of five to eleven he lived in Tromsø, within the Arctic Circle. He met both Ibsen and Bjørnson while a student at the University of Christiania. Lie practiced law, but with few clients was able to write articles for newspapers and journals. His first book was an 1866 poetry volume that went unnoticed, but succeeding works of fiction earned him a government pension, allowing Lie to travel to Rome, Germany, and Paris. His masterwork (in the eyes of some readers), The Family at Gilje, was set down in 1883, but Lie’s most productive period as a writer was after 1893.

Not unlike Adolphe Sax, John Philip Sousa (1854 – March 6, 1932) was also responsible for the invention of a musical instrument, the sousaphone (built by James Welsh Pepper at Sousa’s request in 1893). He led the US Marine Band from 1880 to 1892, then his own Sousa Band until his death. Besides his 136 marches, the “March King” composed operettas and songs and many works in dance form, such as waltzes, galops, and quadrilles. Sousa was selected as one of five prominent American composers for a 1940 set, and “The Stars and Stripes Forever”, composed on Christmas Day of 1896, was commemorated on a stamp of 1997.

American painter Dennis Miller Bunker (1861 – December 28, 1890), born in New York City, was perhaps inspired to a life in art by the fact that his uncle was the illustrator Sol Eytinge Jr. Bunker’s first showpiece was a watercolor that was exhibited at the Boston Art Club in 1881, followed by more such showings at the same venue in the next few years. In the meanwhile Bunker had gone to Paris (1882-83) to study with Jean-Léon Gérôme. He moved to Boston for a teaching post in 1885 and had his first solo exhibition in that year. Shortly thereafter he undertook a number of portraits, with members of the Gardner family and Samuel Endicott Peabody among his sitters. By this time his circle of friends included John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase (whose birthday was just five days ago), William Dean Howells, composer Charles Martin Loeffler, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Bunker married in 1890 but fell ill, probably with cerebro-spinal meningitis, and died three months later, aged only 29. He is buried at Milton Cemetery, with a tombstone designed by Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White. On two stamps from Mozambique we see On the Banks of the Oise (1883) and The Pool, Medfield (1889), which is housed at the MFA.

Unable to pursue a course as a painter because of color-blindness, František Bílek (6 November 1872 – 13 October 1941) turned to sculpture and architecture instead. A representative of the Art Nouveau and Symbolist movements, Bílek found inspiration in the Bible, as in his Moses (1905) and a woodcut, The Prophets Came Out of the Desert (1918), shown on the later of the two Bílek stamps (1972 and 1997). He also carved extensively in various types of wood, and as an architect he created his own villa in brick and stone in the Hradčany district of Prague in 1911.

It’s also the birthday of the great Austrian novelist and playwright Robert Musil (1880 – 15 April 1942), author of The Confusions of Young Törless (1906) and the monumental but unfinished The Man Without Qualities (I started reading it this year, another effort that will likely remain unfinished). Shortly after Musil’s birth in Klagenfurt, his father was named chair of mechanical engineering at the German Technical University in Brno. The young man’s experiences as a military cadet informed his first novel, a Bildungsroman that was made into the film Young Törless in 1966 by Volker Schlöndorff (with arresting music by Hans Werner Henze). Musil, a Catholic, married a Jewish woman in 1911, with both converting to Protestantism as a sign of their commitment (to each other, not, presumably, to their newly adopted faith). He edited literary magazines and then served in World War I, during which time, while on leave in Prague, he met Kafka, whose work Musil much admired. After the war he was a theater critic, had two plays published, the first of which won him the Kleist Prize, and produced a volume of three long stories. From as early as 1921 he was working on the massive Man Without Qualities, but the first two parts were not published until 1930. During this period his finances became precarious, and he received assistance from such figures as Thomas Mann, who helped found the Robert Musil Society in Berlin in 1932. The Nazis banned his books and closed down the Society, but a new one opened in the Musil’s new home of Vienna. In 1939 the couple fled the scourge of Nazism again, this time for Geneva, where Musil died of a stroke. After his death his wife Martha oversaw the publication of a substantial fragment of work constituting Part Three of The Man Without Qualities.

Macedonian composer Trajko Prokopiev (not to be confused with Sergei Prokofiev) was born on this date in 1909. On the centenary stamp he is paired with his compatriot composer Todor Skalovski. (Prokopiev is on the left.) He studied with Miloje Milojević and became a teacher and conductor, running choral societies in Skopje and Sarajevo. Later, after further studies at the Prague Conservatory, he was named head of the music department of Radio Skopje, directing also that city’s symphony orchestra and opera as well as a folklore ensemble. Besides the operas Kuzman Kapidan and Parting, he composed a ballet, Labin and Dojrana, and much film music. He died on 21 January 1979.

One of the great American talents, Mike Nichols (November 6, 1931 – November 19, 2014), was born Mikhail Igor Peschkowsky in Berlin. His mother was a distant cousin of Albert Einstein. In the same year that the Musils fled Berlin for Vienna, Mikhail, then seven, was sent with his brother to join their father in the United States, their mother being reunited with them the next year (1940). His father changed his name to Paul Nichols and established a medical practice in Manhattan. Little Mike lost all his hair as the result of an inoculation for whooping cough and had to wear wigs all the rest of his life. He studied at the University of Chicago and worked as an announcer (for a folk music program that Nichols expanded to include comedy and “odds and ends”) for WFMT. He met Elaine May while performing on stage (she was in the audience), and the wonderful, wonderful team of Nichols and May was formed in 1958. Alas, the partnership endured for only three years. Nichols began directing plays on Broadway with Barefoot in the Park in 1963 (he won a Tony for best director) and moved into film with the splendid Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in 1966. The Graduate followed the next year (these two movies got Nichols his two Best Director Oscars), and three years after that Catch-22 (1970). Among his later projects were the evergreen film comedy The Birdcage (1996), the HBO miniseries Angels in America (2003), and, in 2005, the Broadway production of Spamalot, which earned Nichols another Best Director Tony, his seventh. Spamalot is one of the hit plays selected for a set of British stamps issued in 2011.

There’s no stamp for the Elizabethan playwright Thomas Kyd (baptized 6 November 1558; buried 15 August 1594), author of The Spanish Tragedy.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, and last year that project was expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.