Book Review: “The Mars Room” — Women Behind Bars

The strength of The Mars Room lies in its compelling vision of the stultifying and claustrophobic underworld of women in prison.

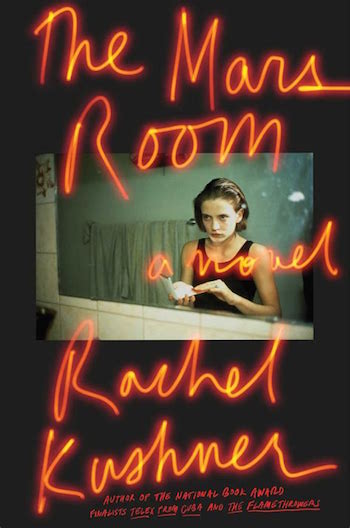

The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner. Simon and Schuster, 352 pages. $27.

By Ed Meek

There are 2.3 million people in prison in the United States in 2018 according to prisonpolicy.org. America is the number one jailor in the world! About ten percent of the inmates are women. That’s right, ninety percent of the people in jail are men. Nonetheless, there’s been an interest lately in the women behind bars, partly inspired by Orange is the New Black, a TV comedy/drama about women who are locked up. The Mars Room delves into the darker “true” story of the women we put away, though it retains some of the comedic elements of OITNB.

The title refers to a strip club where the main character, Romy, works as a lap dancer. The place has a distinct pecking order: “if you showered you had a competitive edge…If your tattoos weren’t misspelled you were hot property. If you weren’t five or six months pregnant, you were the it-girl in the club that night.” Romy works as a lap dancer because she can make good money without actually having sex with the customers. She is a single mother who, in a world with more opportunities, might have gone to college. She has the smarts, but like many women struggling on the bottom rung, she grew up poor and was abused and raped at an early age. Drugs are a necessity for dealing with debilitating reality. The Mars Room poses a new problem: a customer who becomes obsessed with Romy to the point of stalking. When he shows up in her apartment, she defends herself — vigorously. As the novel begins, she is serving two consecutive life terms for murder. As a result, Romy’s son has been taken away from her, vanished into the maw of foster care.

The Mars Room moves back and forth between the present and the past. Romy gives us the inside scoop on what it is like to be locked up, and Rachel Kushner’s research delivers considerable verisimilitude. She interviewed women in prison. We learn that the guards hate working in a women’s prison—they would rather be where the real action is—with the men. There are other lessons: “Certain women in jail and prison make rules for everyone else…If you follow their rules, they make more rules. You have to fight people or you end up with nothing.” Since there is no alcohol, women get meds from the infirmary and save them up in order to bring them to a “party.” The environment is structured to be deadening, dehumanizing. For example, women are woken up at 2 am, shackled, and then driven around the perimeter of the prison. The unnecessary aim is to remind them that life behind bars is no picnic.

Because the novel commences with the main character locked up for life, the plot quickly becomes episodic, focusing on conflicts with, and stories of, the other women in jail. There’s an empathetic woman named Conan who looks like a man, a bully named Teardrop, a baby killer named Laura Lipp who won’t shut up. One surprising conflict: a trans woman is brought into the prison, which causes a shake up in group alignment. Some are in support of her, others are against her. Although these stories are interesting, they don’t generate a plot that moves forward.

Kushner brings in two other characters to expand the scope of the narrative, a cop and a teacher. The chapters on the cop aren’t very effective, but the instructor, Gordon, brings books into the novel, including Thoreau’s Walden. Literature provides a real (and welcome) contrast to the unnaturally constricted setting of the jail. Women prisoners use people like Gordon to illegally procure gifts for them from the outside world. He buys yarn for one woman, mails letters for another. Romy tries to have him to find her son. Gordon is also useful to Kushner because he researches the cases of the prisoners and lets us in on their back stories. (According the Romy, women don’t talk about their crimes to other prisoners.)

My sister-in-law, a minister, volunteered for two years at a maximum-security prison in New York. Like the women in Kushner’s novel, they told her stories filled with poverty, abuse by men, addiction to drugs, and a justice system that made them pay in full for their crimes. Given a fairer justice system, they would probably not have gotten such stiff sentences. In some cases, like Romy’s, the presence of a Michael Avenati or a Gloria Allred in their corner — instead of an overworked, underpaid court-appointed hack — would have made an enormous difference. Any way you look at it, our underfunded justice system, with its parasitic for-profit prisons (which are generating riches for many among our top rung) is morally abhorrent.

Eventually, Kushner comes up with a way to move her plot to a conclusion. But the strength of The Mars Room lies in its compelling vision of the stultifying and claustrophobic underworld of women in prison.

Ed Meek is the author of Spy Pond and What We Love. A collection of his short stories, Luck, came out in May. WBUR’s Cognoscenti featured his poems during poetry month this year.