Classical CD Reviews: Gerald Finzi’s Orchestral Music, Bernstein’s “Wonderful Town,” and Arvo Pärt’s “Works for Violin”

Sir Simon Rattle revisits Wonderful Town with disappointing results; cellist Paul Watkins does magnificently right by Gerald Finzi’s Cello Concerto, and violinist Viktoria Mullova supplies one of the year’s most programmatically-cohesive and thoughtfully-executed albums.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Gerald Finzi’s Cello Concerto is one of those pieces that’s both new and familiar at first hearing. Recognizable in that it clearly hails from a stylistic tradition: echoes of Dvorak’s lyricism, Elgar’s pastoral melancholy, and Saint-Saens’ impish wit dot its pages. But its freshness lies in the fact that, while the music references those touchstones, it’s never beholden to them. Indeed, Finzi’s is as striking and engaging an entry into the genre as they come – perhaps more so, given that it dates from the middle of the 20th century.

Begun just after the composer’s diagnosis of terminal cancer, its first movement is about as turbulent a concerto opening as you’ll find, marked by taut rhythms, sudden (sometimes violent) shifts of mood, and a powerful cadenza. The second one, in contrast, is as tranquil and enchanting as a summer day in the English countryside, meltingly lyrical and unspoiled. Everything’s tied up in a jaunty rondo-finale that’s not quite straightforward – its chromaticism is a mite unsettling and tempo shifts suggest something’s afoot – but, at the very least, satisfyingly energetic.

In Chandos’ new recording with cellist Paul Watkins, all of the Concerto’s contrasts come across magnificently. The lyrical moments swoon with intensity, while a certain resigned aggression marks Watkins’ attacks in the first movement’s tempestuous gestures. The soloist’s tone is never less than warm, though, and his intonation – even in the most devilish runs of double stops – is unfailingly precise.

Sir Andrew Davis leads the BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBCSO) in a robust, full-bodied accompaniment that ably embraces the score’s blend of serenity and chop.

Three substantial Finzi scores fill out the album.

Louis Lortie gives a lush, elegant reading of the keyboard solo of Finzi’s famous Eclogue, Davis and the BBCSO strings providing an impassioned accompaniment throughout. Later on, Lortie gets to exhibit a bit more of his impressive range in Finzi’s Grand Fantasia and Toccata, which channels the composer’s admiration of Bach

Left to themselves, Davis and the BBCSO give a stirring reading of Finzi’s elegiac New Year’s Music. This is pensive music, tender and lonely, and you can hardly ask for a more sensitive reading of it than the piece receives here.

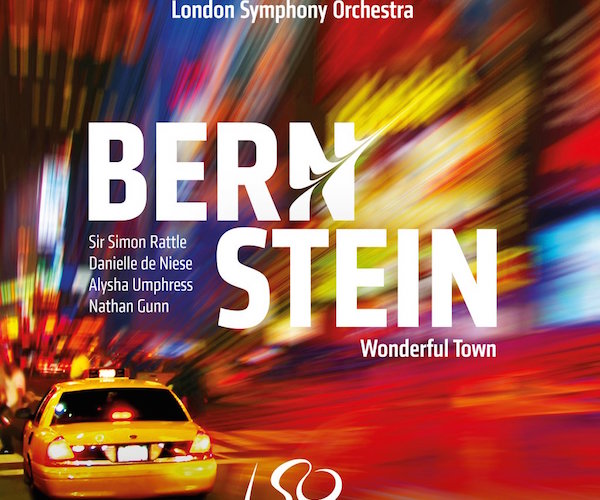

Sir Simon Rattle has an affinity for Leonard Bernstein’s 1952 musical Wonderful Town. Nearly twenty years ago, he recorded it for EMI with the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group and a cast that included Kim Criswell, Audra McDonald, and Thomas Hampson. He conducted it again with the Berlin Philharmonic during his tenure as music director and last season, in his first year as the London Symphony’s music director, made a new recording with that orchestra.

The best thing about this account is, in fact, the playing of the London Symphony (LSO), which had a long history with Bernstein and has now recorded nearly all of his major theater works (the big omission being West Side Story). Surely, Wonderful Town’s orchestral writing has never benefited from technical and stylistic assurance on display here: in a word, the ensemble’s evocations of 1930s jazz, swing, and popular song and dance rip.

If only the same could be said for Rattle’s cast.

Let’s put it this way: if he had brought back Criswell and McDonald, this likely would have been a Wonderful Town for the ages. But he didn’t – and it isn’t.

The biggest problem with this Wonderful Town are leads that, at least over its first half, sound stiff as boards. Danielle de Niese’s Eileen and Alysha Umphress’s Ruth seem too often to be detached and uninterested in their roles. The latter’s “A Little Bit in Love” ought to be a dreamy reprise; here it’s frustratingly intense. Similarly, Ruth’s “A Hundred Easy Ways to Lose a Man” sounds bored. And Ruth’s part in the “Conga” is about as flat as they come.

That said, in Act 2, things generally work better. “Swing” and the “Wrong Note Rag” rival Rattle’s earlier recordings of the piece: they let loose and romp, and the singing is correspondingly lively. But it’s a case of too little, too late.

In other roles, Nathan Gunn’s Bob Baker is a less operatic than Hampson’s 1999 account of the part. “What a Waste” and “A Quiet Girl” are strongly – and warmly – sung. On the debit side, Duncan Rock’s Wreck is rather less charismatic than Brent Barrett’s (in 1999).

The LSO Chorus suppresses their British accents impressively and sing with terrific diction, but the whole performance remains a mixed blessing: consistently dazzling from an instrumental perspective; less than compelling, vocally.

Violinist Viktoria Mullova’s recording of the violin-orchestral works of Arvo Pärt with Paavo Järvi and the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra (ENSO) is among the year’s most programmatically-cohesive and thoughtfully-executed albums.

Most of these pieces – Fratres, Tabula rasa, and Spiegel im Spiegel are probably the best known – were written for Gidon Kremer, who’s also recorded them. But Mullova brings a fresh perspective: a warmness of tone and directness of expression that’s not (necessarily) connected to their points of origin.

Her accounts of the familiar pieces are compelling.

Fratres, in Pärt’s 1991 adaptation for violin, strings, and percussion, is, in her hands, both contemplative and muscular. Tabula rasa, with its austere textures and powerful sonorities (highlighted by the bell-like gestures of a prepared piano), builds to a similarly potent expressive climax. And Mullova’s Spiegel im Spiegel (with pianist Liam Dunachie) marries expressive purity with understated dramatic and spiritual insights.

Two minor post-1995 pieces are well-played and smartly-placed palate-cleansers. Pärt’s Passacaglia evokes Bach and Shostakovich with it sequential riffs while Darf ich… kicks off the album with a certain liturgical sobriety.

Järvi leads the ENSO in accompaniments that never lack for concentration or fervor and Florian Donderer matches Mullova color-for-color as the second violin soloist in Tabula rasa.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: -Arvo-Pärt, Chandos, Gerald Finzi, Leonard Bernstein, LSO Live, Onyx, orchestral music, Wonderful Town