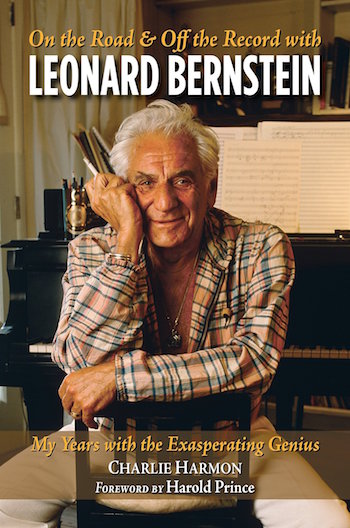

Book Review: “On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein”

If Charlie Harmon’s story jumps around a bit and reads rather like a series of diary entries, it’s at the very least engaging and, for the most part, entertaining.

On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein: My Years With the Exasperating Genius by Charlie Harmon. Imagine Publishing, 272 pages, $24.99.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Surely most assistants don’t write memoirs. But when your boss was Leonard Bernstein, it’s a safe bet that the work – and experiences – were singular. So it was for Charlie Harmon, Bernstein’s penultimate adjunct, whose tenure with the maestro (who almost everybody, Bernstein included, referred to as LB) covered about half of the great man’s last decade. As Harmon’s gossipy new memoir, On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein: My Years With the Exasperating Genius, makes clear, though, the gig was anything but a cakewalk.

By the time Harmon answered a vaguely-worded classified and joined the entourage, LB was on a downward spiral. Pushing sixty-five and on the heels of a decade of musical and personal tumult, he was in a bad place, emotionally. With no one to rein in his worst impulses, Bernstein could be a chaotic mess. Indeed, as Harmon recounts, LB’s frenetic lifestyle was largely fueled by a potent mix of drugs and alcohol. If he wasn’t hopped up on “halfsies” of Dexedrine or inebriated, Bernstein was just as likely to be fighting through some mix of depression, insomnia, and/or self-loathing.

His behavior veered wildly.

Sometimes it was bizarre. Early on, Harmon relates the story of a dinner at a swanky Bloomington, IN restaurant with Indiana University School of Music Dean Charles Webb and his wife, Kenda, during which Bernstein took a cork from a wine bottle, charred it in a candle on the table, and proceeded to paint his and his dinner-mates’ faces (including Harmon’s) with the ash, to the bewildered stares of the restaurant’s other patrons. Later, there’s a birthday party for Bernstein’s son, Alexander, during which LB inexplicably smashed the birthday cake to a pulp with his fist in front of all the guests.

Other times, his conduct was just unseemly. At one point, Bernstein’s receiving guests in his hotel suite nude except for a waist-length leather “Sharks” jacket (a gift from the 1980 West Side Story revival cast). A couple years later he’s taking an all-male troupe of Tanglewood composition and composing fellows out for a night on the town (or, more accurately, the Seven Hills Inn in Lenox, MA). “I prayed everyone at Seven Hills was of legal age,” Harmon writes – and he proceeded to take the night off.

Indeed, Bernstein’s sexual appetite in On the Road and Off the Record suggests a voracious twenty-something constantly on the prowl, not a guy in his seventh decade. Harmon recounts a parade of LB’s lovers, one-night stands, and other shenanigans, culminating in perhaps the book’s most shocking passage where Bernstein grabs Harmon’s crotch late one night. We’re told this was a three-months-on-the-job ritual to which all LB’s assistants were subjected. But Harmon’s response to the experience reads like that of a sexual assault survivor – which, to some degree at least, he was.

Granted, none of this information is new: anyone who’s followed Bernstein’s life in print, at least since Joan Peyser’s trashy 1987 biography, has been privy to rumors along these lines. But to have them confirmed in such detail as Harmon provides is, to say the least, jarring.

Despite LB’s demons frequently holding sway, the picture Harmon paints of his term isn’t entirely off-putting or grim.

Bernstein’s itinerant life as a conductor in the early-‘80s is well documented here. Harmon was responsible for arranging many of the details of LB’s travels and the narrative skips quickly from Indiana to Los Angeles to Israel, Vienna, Munich, New York, London, and a host of other locales.

There were concerts, tours, and recording sessions, including some of Bernstein’s most notable interpretations of his last decade. Indeed, Harmon’s work with Bernstein coincided with some of the musician’s more controversial recorded projects, like his 1982 Elgar disc and his 1984 recording of West Side Story, a three-day project during which nothing went smoothly.

Leonard Bernstein on the TV program “Ominbus.”

Much of Harmon’s work routine was humdrum. He recaps the minutiae of days spent in the office and on the road: packing and unpacking twenty-some suitcases filled with clothes, books, music, and LB’s travel paraphernalia (which ranged from medications to a noise machine to a stuffed monkey called Moneto); setting up media interviews; responding to ticket requests from LB’s friends and relatives; making last-minute travel arrangements; catering to LB’s whims; and contending with the challenges presented by Bernstein’s cantankerous, often bullying, manager, Harry Kraut.

Lots of faces pass by. Some of them – like Julia Vega and Ann Dedman (LB’s housekeeper and cook, respectively) – helped to anchor Harmon as he started navigating Bernstein’s orbit. Other Bernsteins (LB’s three kids, Jaime, Alex, and Nina, as well as his siblings, Shirley and Burton) make regular appearances, as does the family’s matriarch, Jennie (“You’ll never know till you try,” was the memorable advice she gave Harmon while they were chatting about ambition – or lack thereof – during a limo ride between Newark International Airport and LB’s Dakota apartment).

LB’s dinner guests read like a who’s-who of late-20th-century American culture and includes the likes of Elie Wiesel, Lewis Thomas, and Adolph Green. At one point, there’s a party at Hickory Hill with Ethel Kennedy and a number of political and media luminaries (including Ted Kennedy and Diane Sawyer). Various Bernstein collaborators like Stephen Sondheim, Stephen Wadsworth, and Betty Comden, as well as friends like Lauren Bacall, come and go, as do a host of classical music luminaries: Isaac Stern, Christoph Eschenbach, and Michael Tilson Thomas among them.

Through it all, Bernstein remained vigorously active as a composer, pianist, and teacher. In part, thanks to Harmon’s cajoling, his opera A Quiet Place was finished in time for its 1983 premiere. Alas, the piece badly misfired with audiences and critics at its premiere. But the experience of helping arrange the score for workshops and eventual publication led Bernstein to entrust Harmon with his music after his death.

By that time there had been a new assistant, Craig Urquhart, for several years and Harmon had taken on other roles in the Bernstein industry. It was, ultimately, a good thing for him: Kraut forced him out of his job in 1986, by which time he was at his wit’s end. Some years of therapy and distance from Bernstein’s sun seemed to have done the trick, and Harmon presided over the publication of new editions of several of LB’s theater works over most of the ‘90s. Then that gig ended, too, after the last of a countless series of fights with Kraut, who died in 2007.

What to make of it all, then?

Harmon’s a capable writer and, if his story jumps around a bit and reads rather like a series of diary entries, it’s at the very least engaging and, for the most part, entertaining. Among recent Bernstein literature, On the Road and Off the Record makes for a particularly welcome complement to Jonathan Cott’s Dinner With Lenny and Jack Gottlieb’s Working with Bernstein.

Harmon’s assessment of his old boss is remarkably detached, given the craziness of the job and how it ultimately wore him out. There’s a remarkable lack of judgment and degree of understanding involved: clearly Harmon’s spent a lot of time analyzing Bernstein’s life and the forces that shaped it these last couple of decades. Ultimately he chalks LB’s most outrageous behaviors up to his inability to come to terms with the 1978 death of his wife, Felicia. That’s a perfectly reasonable explanation, given Bernstein’s devastation by her passing and by what he saw as his own role in hastening it. Felicia, often enough, was a guardrail who could hold him in some sort of check; once she was gone, anything could – and did – go.

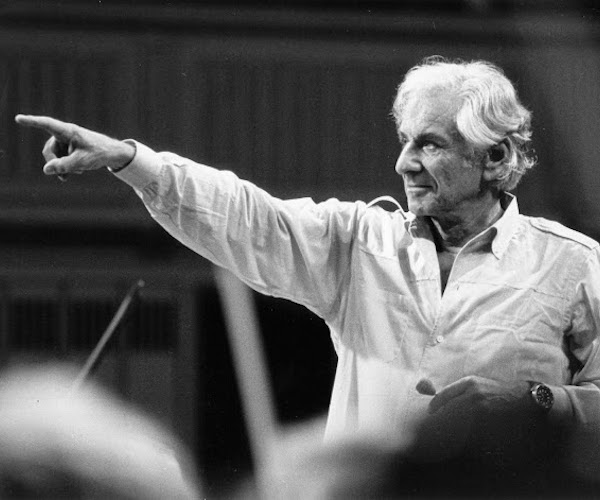

Leonard Bernstein conducting a performance of “Candide.” Photo: Operalia.

So On the Road and Off the Record documents the aftermath of her demise, showcasing those two sides of Bernstein that were constantly at odds: the one, a man of unchecked ego, celebrity, wealth, and talent; whose whims were capricious; judgments not always sound; and who could be casually petty, selfish, debauched, shamefully cruel, and remarkably vulgar.

At the same time, LB could be surprisingly self-aware (“People like me for what I do, not for who I am,” he tells Harmon in a revealing, post-Dexedrine-crash exchange); generous to a fault; brilliant – in word games, writing music, discussing any subject under the sun; funny and charming; an inspired teacher; and a musician with few equals.

Of course, such oppositional dynamics are present in all of us; they’re commensurately exaggerated in those giant personalities that walk among us. They shaped the person of LB and to attempt to reconcile their contradictions is impossible. To his credit, Harmon doesn’t do that; nor does he try to make the virtues of one compensate for the flaws of the other. He simply gives us Bernstein as he was.

At its best, then, what his book manages by drawing out these divergent characteristics is to lend a deeper understanding of Bernstein’s music (especially the late pieces like A Quiet Place and Arias and Barcarolles), which unashamedly – and sometimes very uncomfortably – traffic in these very contrasts. In so doing, Harmon provides his old chief perhaps the best and most necessary service he could have aimed for.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

For an unexpectedly candid portrait of life from the inside with Leonard Bernstein – also read Famous Father Girl ” A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein ” / Harper- Collins 2018 by Bernstein’s eldest daughter, Jamie. The Bernstein Celebration Concert that took place at Tanglewood this past August on the occasion of what would have been Bernstein’s 100th birthday will be broadcast on PBS television’s Great Performances on Dec. 28th at 9 p.m.