Dance Review: Dorrance Dance at Jacob’s Pillow — Stretching the Boundaries of Tap

Nicholas Van Young supplied an astounding display of virtuosity that seemed to amaze even the dancer himself.

Dorrance Dance at Ted Shawn Theatre, Jacob’s Pillow, July 18 through 22.

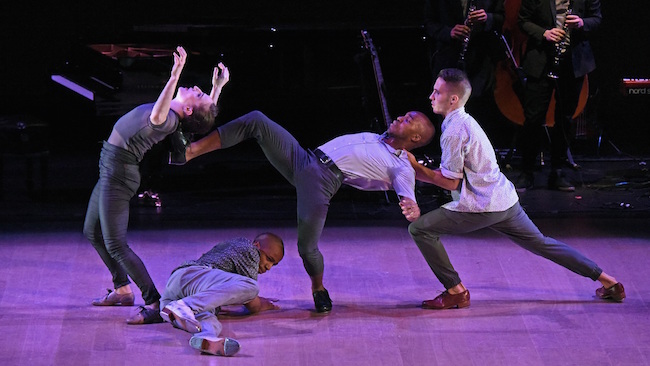

Dorrance Dance in action at Jacob’s Pillow. Photo: Kevin Parry.

By Mary Paula Hunter

Michelle Dorrance, the creative force behind Dorrance Dance, presented two very different works at Jacob’s Pillow this season. The premiere All Good Things Come to an End opened the program. Perhaps over time this work will coalesce, but at this early stage of its development All Good Things came off as a confused attempt at storytelling through tap. The program’s second half featured the much heralded Myelination, a show-stopping ode to the inventiveness of rhythmic tap as well as a boundary-stretching work that often pushes tap composition into the realm of concert dance through exciting juxtapositions of phases and techniques, overlapping rhythms, and a brilliant incorporation of duets into large groupings.

All Good Things began with dancers holding up signs that seemed to announce the end of the world. Signs flew back and forth across the space, preparing us for a debunking of long-held myths: The Myth of America, The Myth of Narcissus, etc. But the dancing rarely advanced beyond proclaiming the dystopian concept. For the most part, Dorrance offered up standard rhythmic tap: lots of syncopated phrases and much rushing about in the retrieval and stacking of signs.

Luckily for the packed matinee audience, pieces of choreography stood out against this vague warning about the end of the world. The lovely “Cane and Able” was a duet for two dancers and four canes. Like ventriloquists, the dancers manipulated the canes so that feet and canes were in constant conversation. “Cane and Able” proved that timing and choreographic ingenuity are at their best when steps serve an overall concept.

Equally inventive was a quartet in a tight grouping. Perhaps marooned on a raft, dancers moved heels and toes by way of a skating, lightly tapping locomotion. This time canes were used to punt the group along to the stage wings, where dancers disembarked by lifting their legs high onto imaginary docks of safety. Were these refugees fleeing across dangerous waters? Perhaps relating to The Myth of America sign, this was a relevant dance, to say the least.

How the Ugly Duckling dance or the Narcissus dance — both prop heavy compositions featuring big shoes and lots of mirrors — related to impending doom was never clear. In the end, All Good Things had the feel of a variety show. Perhaps, stripped of signs and its vague narrative, the work might resonate as an ode to vaudeville. The music, familiar selections from Artie Shaw and Fats Waller, smacks of a bygone era. In this context, though, it came off as more nostalgic than challenging.

Myelination is divided into short chapters that go back and forth between groups and solos. The work began with a much expanded company covering the stage in lines that resembled notes on a staff. Behind the performers was a band, made up of keyboard, bass, synthesizer, vocals, and clarinet. Music and dance engaged with each other throughout the 40-minute work, often in opposition — trance music to pounding feet, piercing synthesizer to complex rhythmic tap that worked against the wall of sound. Sometimes, the music seemed to converse with the tapping sounds ,lending an improvised, jamming feel to the experience.

Dorrance is at her most inventive when choreographing group works in which she challenges tap’s reliance on solo-ism — the dancer as virtuoso or corps as soloist made to perform in drill-like synchronicity. Her techniques for group choreography cover a wide range: splitting the stage with contrasting action on either side; creating files of dancers that face each other or the wings as opposed to the audience; and, the most interesting of the lot, she often embeds a pas de deux or a soloist within the corps — a subversion of the traditional hierarchy in which the corps frames the soloists or duo. In the latter configuration, Dorrance challenges us to locate the higher-ups within the crowd — before they dissolve into the anonymity of corps work.

In Myelination, Dorrance conquers the pas de deux as well as the large group numbers. A pas de deux between guests Ephrat Asherie and Matthew West brilliantly underlined Dorrance’s disregard for stylistic boundaries; it could easily stand on its own in a mixed-bill. Hip Hop masters, these two floated and glided like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers through a range of movements, from modern to hip hop. This was an iconic postmodern duet, handstands and flips juxtaposed with spirals of the spine and the relaxed falls of the Release Technique. The dancers were no longer bound by one specific technique or style.

On the one hand, Myelination contained one too many solos, to the point that the piece sometimes crumbled into pieces. Still, certain solos stood out, particularly Nicholas Van Young’s racing study in gentle and pounding tapping in which he watched his feet as often as we did. It was an astounding display of virtuosity that seemed to amaze even the dancer himself.

Mary Paula Hunter lives in Providence, RI. She’s the 2014 Pell Award Winner for service to the Arts in RI. She is a choreographer and a writer who creates and performs her own text-based movement pieces.