Book Review: “Big Deal — Bob Fosse and Dance in the American Musical”

Big Deal differs from other Bob Fosse biographies in its focus on the dances themselves.

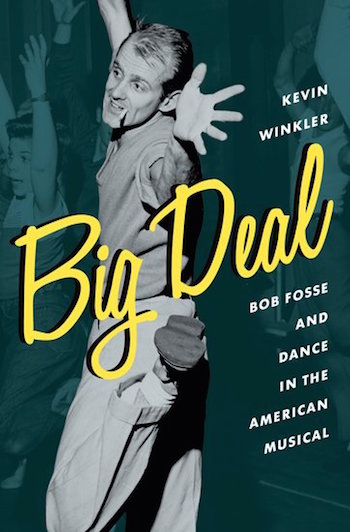

Big Deal: Bob Fosse and Dance in the American Musical by Kevin Winkler. Oxford University Press, 368 pages, $29.95.

By Christopher Caggiano

Bob Fosse is singular among musical theater practitioners. No other choreographer’s work is as instantly recognizable, and few have had lives as fascinating. In addition, Fosse is a morass of contradictions: self-assured and self-deluded, full of genius and full of crap. No wonder there has been so much continuing interest in his life and his work, including the biographies Fosse (2013) by Sam Wasson and All His Jazz: The Life and Death of Bob Fosse (2009) by Martin Gottfried.

Add to that mix the latest attempt to capture, in print, the bedeviling magic of Fosse — Big Deal: Bob Fosse and Dance in the American Musical. This is author Kevin Winkler’s first book and, as we’ll see, his lack of experience shows. He does have ample experience as an archivist, curator, and administrator at the New York Public Library, and he certainly knows the landscape from his previous career as a professional dancer.

Big Deal differs from other Fosse biographies in its focus on the dances themselves. Wasson delves more into the interpersonal relationships in Fosse’s life, while Gottfried is a bit more sensational as he goes about uncovering lurid details. Winkler aims to be more of a dance archeologist.

As the biographer states in his introduction, his mission in writing the book was “to pull apart the Swiss watch precision of [Fosse’s] dances and understand … the wide-ranging sources of his movement vocabulary.” Also, Winkler pays particular attention to how Fosse’s three wives were instrumental inspirations regarding the various big breaks and breakthroughs in the artist’s life.

With the eye of a dancer, Winkler takes a show-by-show, dance-by-dance, step-by-step approach to Fosse’s career. He seems intent on creating a historical record of Fosse’s dances, and that is admirable. But the results are often predictably tedious — rich in painstaking detail but lacking in overall perspective. As a result, Big Deal feels more comprehensive, in a documentary sense, with respect to Fosse’s choreographic output, than either Wasson’s or Gottfried’s tomes. But Winkler’s style is considerably more pedestrian.

To his credit, the biographer strives for balance in his analyses, determined to avoid the pitfalls of hagiography. For example, in describing the evolution of Fosse’s style during the ’70s, Winkler notes a move from “traditional musical comedy … to a more lyrical, self-serious approach that [Fosse] could not always support.”

Winkler attempts to speak with an authoritative voice and, for much of the time, it is convincing. But, although he sounds certain of his arguments, he frequently ends up overstating his case. In discussing the significance of Jerome Robbins’ work as director and choreographer of West Side Story, Winkler asserts that “[the show] proved decisively that it was a choreographer who could most effectively harness a musical’s various elements into an integrated whole.” Really? So only a choreographer can effectively direct a musical? Many would beg to differ, including Harold Prince, Jack O’Brien, Bartlett Sher, Diane Paulus, Tina Landau, Rachel Chavkin … I could go on.

Particularly risible is Winkler’s claim that, with the opening sequence of the film All That Jazz, “Fosse virtually created the modern MTV music video.” So, Fosse singlehandedly gave rise to the MTV style? Um … debatable. I may have been spoiled by having gone through two books by Ethan Mordden just prior to reading Winkler’s. Mordden is one of the most prolific and respected musical-theater historians we have, unimpeachable in both his skill as a writer and expertise in his field. Compared to that high level of knowledgeable maturity, Winkler’s work feels like the effort of an ambitious, hard-working amateur.

The biographer may have worked in musical theater, but his grasp of the form’s history is shaky at times. Winkler posits that, with West Side Story, “Robbins eliminated the traditional overture and opening vocal number.” The wording suggests Robbins did it first. However, both Carousel (1945) and Guys and Dolls (1950) were staged without overtures and opening choral numbers years before West Side Story (1957). Winkler also refers to the “satirical athleticism” of Michael Kidd’s dances for Finian’s Rainbow, Guys and Dolls, and Can-Can, but Finian’s Rainbow is the only genuinely satirical show on his list.

On an admittedly picayune level, Winkler’s prose contains a distracting number of rookie slips in grammar and diction. For example, he insists that the musical “[Gypsy]’s depiction of both the twilight of vaudeville and burlesque’s transition to coarse comics and strip acts had been playing out across the United States for some time.” This is poorly worded at best. The “depiction” wasn’t playing out. The decline was. Winkler also uses “notoriety” when he means “fame,” “ironic” when he means “coincidental,” “disinterested” when he means “uninterested,” and “inferring” when he means “implying.” He also refers to a sequence in a musical piece in which the music drops out as “tacit,” whereas any musician will tell you that the proper term is “tacet.”

Bob Fosse in action. Photo: Wiki.

One of the strongest features of Winkler’s writing is his knack for succinctly establishing the cultural context of Fosse’s shows. He aptly describes the film Cabaret as “one of the touchstone films of the 1970s … [bringing] new life to a moribund film genre and, as musicals seldom do, [connecting] with contemporary politics and sexuality.” Winkler also provides numerous insights into the underpinnings of Fosse’s dances, as well as supplying insightful comparisons between Fosse’s work and that of his peers.

So Big Deal gets the big picture right. Winkler is aware of the central irony of Fosse as an artist. Fosse didn’t play well with others, and over the course of his career worked with fewer and fewer collaborators, his isolation driven by his fear that others would compromise his creative vision. The biographer notes that “Fosse achieved his goal of total control, but it would be hard to argue that his work had not benefited from the creative struggle of collaboration with artists like John Kander and Fred Ebb.”

Various qualifications notwithstanding, Winkler’s volume is a welcome addition to the field of Fosse. Toward the end of Big Deal, he neatly captures the artist’s bewilderingly contradictory nature: “About [All That Jazz], [Fosse] sounded plaintive when he said, ‘I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done, but I don’t know how good it is.’”

Christopher Caggiano is a writer and teacher based in Boston. He serves as Associate Professor of Theater at the Boston Conservatory at Berklee. His writing has appeared in American Theatre and Dramatics magazines, and on TheaterMania.com and ZEALnyc.com.

Tagged: Big Deal: Bob Fosse and Dance in the American Musical, Bob Fosse, Kevin Winkler