Jazz Review: A Dispatch from the 39th Montréal Jazz Festival

Among the festival’s highlights: pianist-singer Jeremy Dutcher, who arrived on the stage at the tiny space Gésu dressed in shorts and a long flowing black robe with a hood.

Herbie Hancock performing at the 39th Montreal Jazz Festival. Photo: Benoit Rousseau.

By Michael Ullman

I am in the midst of the 39th Montréal Jazz Festival (June 28 through July 7). I can’t say that I am covering it. No one person could. It would be more accurate to say that the ten day festival pretty well covers central Montréal. The Festival takes place in, according to my count, 42 different venues: symphony halls, night clubs, churches, huge outdoor stages, and odd rooms that could be described as musty hideaways. There are jazz musicians of international stature playing here…Herbie Hancock, Dave Holland, Brian Blade, and Ingrid Jensen … as well as dozens of local heroes. The festival has also reaches out to musicians of different genres, such as Ani DeFranco and Ben Harper. There are hundreds of performances, offering a dizzying whirlwind of alternatives.

Montréal has a long history with jazz. In the nearly blistering heat, I and a few other intrepids went on a tour of the music’s history in the city, beginning near the train station, in an area nicknamed Le Coin, or corner. It was populated at one time by porters for the trains and their families. The clubs, some large, followed the growing crowds. In the ’30s, dance halls that could accommodate several thousand customers featured the major big bands: Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway played Montreal, as did Louis Armstrong. The scene degenerated in the ’40s and ’50s. But it was a thrill to stand in front of the Club Paree and listen to a version of “Ornithology” that Charlie Parker had recorded inside. Its no wonder the Montréal’s populace are engaged by the Festival — even boisterous and appreciative.

On Monday night, at the concert room in the Monument National, I heard the Orchestra national de jazz de Montréal perform the music of the now 80 year old composer Carla Bley. She was supposed to conduct, but withdrew because of ill health. Christine Jensen took over the reins: the evening featured a series of piano players, each with his or her own style, playing with the ‘big band.’ The first, Gentiane MG, played a long, sweetly lyrical introduction that sounded to my ears like a version of “My Foolish Heart.” She yielded to the bass player. Then the band, which has been playing together since 2012, took over. Some of Bley’s humor emerged in her tune “On the Stage in Cages,” which turned into a kind of woozy waltz. Pianist Marianne Trudel was featured on “Greasy Gravy.” The composition was not (despite the title) a funk tune; rather, the alto saxophonist played its melody in a lyrical Johnny Hodges style. Among the high points of the evening: performances from pianist Helen Sung and trumpeter Ingrid Jensen. Montréal-born Francois Bourassa played a solo tribute to Bley while the Orchestra National de Jazz de Montréal listened.

The next night, playing with his quartet at L’Astral, Bourassa seemed to be channeling Bley’s creative spirit. One of his numbers was dedicated to, and meant to evoke, two of his musical influences: Bley and Stockhausen. It was called “Carla and Karlheintz” and, as one might expect, it was made up of two parts, or approaches: a slamming insistent rhythmic purr and a more fluttery gentle section. In the latter, Bourrassa played pedaled chords, generating sounds that were a little dreamy. He’s a fascinating musician, with a full-bodied, two-handed style that often seems free regarding its improvisation. Yet his band is tight and disciplined: on “Onze Beignes,” flutist Andre Leroux played the melody, or what I took to be the melody, via a series of rushed phrases and then sudden pauses. It seems as if he were awed by his own presumption. At one point, he and Bourassa played high staccato notes. Between numbers, various members of the audience yelled things at the pianist: I heard one request for a particular composition, but otherwise they were examples of good-natured heckling. Bourassa’s music is challenging, but he has a committed following that are engaged, to say the least — some of them must think of him as family.

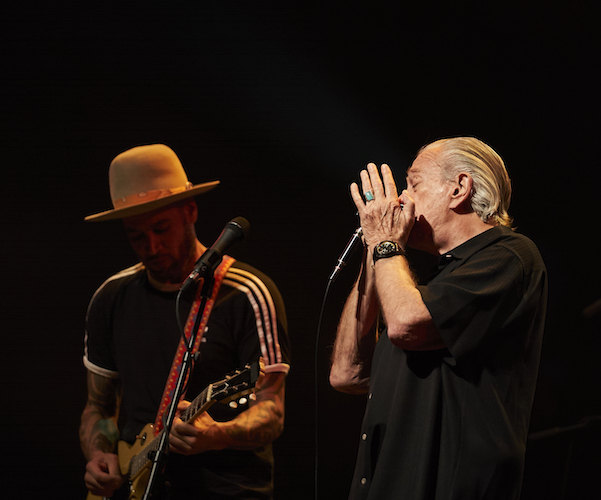

Ben Harper performing with Charlie Musselwhite at the 39th Montréal Jazz Festival. Photo: Benoit Rousseau.

I rushed to hear blues vocalist and guitarist Ben Harper perform with harmonica player Charlie Musselwhite. I got to the packed concert hall in time to hear Harper receive the Ella Fitzgerald Award from the Festival. Harper informed us he and Ella had several things in common: a commitment to human rights; a common home town in Los Angeles; and they each had three spouses. He then played a solo version of “Summertime.” Perhaps he was thinking of Ella’s recording of Porgy and Bess with Louis Armstrong. Most of the set featured his high powered, heavily amplified blues.

Finally, a pianist-singer Jeremy Dutcher, who arrived on the stage at the tiny space Gésu dressed in shorts and a long flowing black robe with a hood. He is, he told us, one of the last 100 people who speak the native language of the territory in and around New Brunswick, Canada. His set was “a ceremony” in which he plays songs written over a hundred years ago by those natives.

Dutcher’s story is fascinating. His parents spoke the virtually extinct language. Somehow, the singer discovered that, 110 years ago, an anthropologist recorded (on wax cylinders) native singers singing the area’s traditional songs. Some of the vocalists included Dutcher’s ancestors. The cylinders were placed in a museum; the language languished; the people dispersed. Dutcher found out about the recordings, and for the last five years he has been learning the songs and working on ways to perform them in his style. His approach is unusual: his piano playing is lyrical, modernist-tinged. His vocals are also distinctive: almost operatic, but he also draws on heavy vibrato, sometimes falsetto. Dutcher can sound intense: he sang one trading song that, because of its overwhelming force, made the listener wonder how well business was going. More often he was modulated, as when he sang a song meant to welcome the elders, as well as other ceremonial numbers. At the end the performance Dutcher stood up and bent over so that his head was inside the piano. He looked like a near-sighted piano tuner, and chanted into, or virtually onto, the strings, creating eerie overtones. It was a unique ending to a one-of-a-kind concert.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.)

Tagged: Ben Harper, Carla Bley, Charlie Musselwhite, Christine Jensen, Francois Bourassa, Herbie Hancock, Jeremy Dutcher