Visual Arts Review: “Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900” — A Fabulous Surprise

Who knew that there were dozens of first-rate female American, Scandinavian, German, Swiss, French, and Russian painters in Paris in the second half of the 19th century?

Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA through September 3.

By Helen Epstein

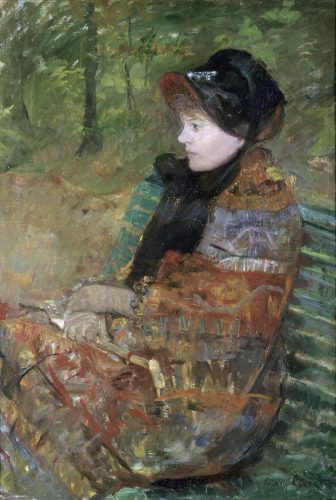

Mary Cassatt, “Autumn, Portrait of Lydia Cassatt,” 1880. Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris. Photo: Bulloz © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

A kind of giddiness wafted through the crowd at the entrance to the Clark Art Institute’s exhibit Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900 both times I visited: museum-goers were pointing at the wall-size black and white photo of 50 nameless female art students at the Académie Julian circa 1885, just a fraction of the first wave of females who came to Paris to study art. Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900 shows us up close what several of these artists looked like, how and where they worked, and what 33 of them made. The exhibit includes some 70 paintings chosen from over 60 museums, mainstream as well as far off the beaten track. Some works are by well-known artists, such as Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, and Rosa Bonheur, but many are a fabulous surprise.

Who knew that there were dozens of first-rate female American, Scandinavian, German, Swiss, French and Russian painters in Paris in the second half of the 19th century? Who knew that they produced such a variety of canvases, small and large, despite strict government restrictions on dress, work space, and access: hunting scenes and animal paintings, large landscapes as well as domestic scenes of tea parties, bourdoirs and nurseries — even an autopsy scene. Some, like the French upper middle-class Berthe and Edma Morisot, enjoyed the friendship or collegiality of male artists Corot, Daubigny, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Puvis de Chavannes, Stevens, and Manet, though they were depreciated by them. Degas used Mary Cassatt as a model, but never portrayed her as a painter. A number of these female artists sat as models for male painters. Others — especially the foreigners — seem to have lived a separate existence. I was struck by the absence of characteristic Parisian subjects: café, bar, backstage or brothel scenes, people reading newspapers or playing cards, and the absence — except for babies — of nudes. Was there such a thing as a “female gaze” in 19th century Paris? What did it gaze at?

Former Musée d’Orsay curator Laurence Madeline, who created the show for the American Federation of the Arts, was more focused on the pioneering effort of gathering these works together rather than delving into these provocative questions. As she told it at the Clark Art Institute last month, it was not easy to assemble this exhibit. Some paintings had to be dug out of storage, where they had been consigned many decades ago, while others had to be pried from museums that are capitalizing on newly lucrative feminist interest in women artists.

So, who were these women and what did they look like?

Marie Bashkirtseff, “In the Studio,” 1881. Dnipropetrovsk State Art Museum, Ukraine, KH-4234. Photo: Dnipropetrovsk/Bridgeman Images.

Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900 opens with “In the Studio” by the gifted, feisty, and short-lived Ukrainian Marie Bashkirtseff. In this realistic community portrait, Bashkirtseff paints the studio where she studied in 1881 — the Académie Julian. Rodolphe Julian founded his school in 1868 in order to prepare men and women for exams at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Since most foreigners could not meet the École’s stringent French language requirement — and women were barred until 1897 — the Académie Julian provided an alternative education. Men and women alike could receive permission to copy painting in the Louvre – Harper’s Weekly published a Winslow Homer engraving of that intermingling in 1867. But the idea of men and women drawing nude figures together in a closed and private space offended norms of the time, so Julian created four sub-studios, one of which segregated women into their own space.

Bashkirtseff, a daughter of minor Russian nobility whose girlish diary was perhaps the most famous before Anne Frank’s, created some 230 works of art between 1877 and her early death of tuberculosis in 1884. She situates herself in the foreground in dark and modest dress, palette in hand, engaged in an intense discussion with another woman. Her painting affords us a glimpse at a class of 19th century women training to be artists; the obligatory norms of impeccable female dress stand in ironic contrast to the messy art materials, the interactions among students, and the unusual arrangment of fully-dressed women depicting a boy model, who is not.

I was fascinated by the pictures that show us these painters up close. We are used to viewing the portraits and self-portraits of male artists from Rembrandt to Lucian Freud. The Clark owns a couple of dozen, including three self-portraits by Renoir. But, before the twentieth century, portraits of women artists are scarce. In fact, as Madeline writes in the superb exhibit catalogue, “Women rarely appear in nineteenth century French representations of artistic communities in any medium, visual or literary.”

Berthe Morisot and Pittsburgh-born Mary Cassatt (who spent most of her life in France) are perhaps the most familiar 19th century female painters. Both are well represented in Massachusetts museums, but we have never seen them at work. Edma Morisot’s somber 1867 portrait of her younger sister Berthe lingers in my mind. Berthe married Édouard Manet’s brother and gave birth to a daughter, yet she remained a successful and prolific artist until her death; Edma stopped painting after her marriage to a naval officer and becoming a mother.

The crucial importance of supportive friends and partners is highlighted throughout this show. We see it illustrated in Swiss painter Louise Breslau’s large portrait of herself and her two 20-something roommates — another painter and a singer. Danish painters Anna and Michael Ancher’s “Judgement of a Day’s Work” shows the married couple — both painters — at home, ostensibly critiquing a completed canvas. Such heterosexual artistic partnership was extremely rare in 1883 — even in the progressive art colony of Skagen, Denmark, where Anna grew up.

I was astounded by how many Nordic painters came to Paris in the latter part of the century, even though many of them, such as Swedish painter Hanna Hirsch-Pauli, were permitted to study at their native state institutions of art. The daughter of a music publisher, Hanna studied from 1885 until 1887 at the Académie Colarossi, sharing a studio with a painter friend. Her portrait of another friend, Finnish artist Venny Soldan-Brofeldt, despite being seen as extremely provocative for its time, was accepted at the Paris Salon in 1887. In it, Venny is sitting on the floor of her studio like a peasant or beggar, her left hand holding a clump of clay. Her pose and expression are startling even today; they were excused back then as evidence of a “Nordic liberated lifestyle” foreign to the French.

Hannah (Hirsch) Pauli, “The Artist Venny Soldan-Brofeldt,” 1886-87. Gothenburg Museum of Art, Sweden. Photo: courtesy American Federation of Arts.

Perhaps the most formidable portrait in the exhibit is of “the matriarch and model for all women artists,” Rosa Bonheur. Bonheur had sat for portraits several times before, but in this one she was a year away from her death. American painter Anna Elizabeth Klumpke – who had grown up in San Francisco playing with a Rosa Bonheur doll — has posed her at her easel, with her Légion d’Honneur rosette prominently displayed on a lapel.

The magisterial, white-haired Rosa Bonheur portrayed in this 1898 portrait was born in 1822. Apprenticed to a seamstress at the age of 12, Rosa was a failure at couture. Only after that did her painter father allow her to follow in his footsteps. Rosa not only copied paintings at the Louvre, but sketched dead animals in Paris slaughterhouses and dissected them at the national veterinary institute. For visits to this and other ‘low class’ venues she was obliged to obtain official permission to wear men’s clothing. Her realist canvas “Plowing in Nivernais,” a depiction of cattle that measures nearly 4.5 x 8.5 feet, was exhibited in 1849 to wide acclaim and was purchased by the government. It eventually wound up in the Musée d’Orsay.

Anna Klempke, “Rose Bonheur,” 1898. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

Like author George Sand, a generation before her, Rosa was praised for possessing the genius of a man. Unlike Sand, she had no interest in men. As critic Karen Chernick has written, both her intimate partnerships began with a portrait. “In 1836, when she was 14, her father was commissioned to paint a portrait of a local girl, Nathalie Micas. Almost immediately, Bonheur and Micas felt a strong affection toward one another, and they eventually decided to spend their lives together. Micas supported Bonheur as she built her illustrious career, largely tending to household affairs so that Bonheur could focus on painting. Their partnership continued for 50 years, until 1889.”

A few months after Micas’ death, at a business meeting with an American horse dealer, Bonheur met Klumpke, 34 years her junior. While studying painting in Paris, Klumpke had fallen in love with, and copied, Bonheur’s “Plowing in the Nivernais.” The sale of that painting, for 1,000 francs, enabled her to pay her tuition at the Académie Julian. Klumpke later set up residence in Boston, but in 1898 she asked to paint Bonheur’s portrait and wound up moving in with her now elderly model. When Bonheur died a year later, Klumpke founded the Rosa Bonheur Memorial Art School for women artists.

Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900 is loosely organized into rooms designated by overlapping themes –- The Art of Painting, Lives of Women, La Toilette, Picturing Childhood, Jeunes Filles — rather than chronologically, or by style, country, or painter.

This curatorial strategy frustrated me on a number of counts: many of the paintings fit into more than one category; the conventional domains of “women’s lives” have already been thoroughly represented in museums around the world; and I wanted to be able to look at the work of unfamiliar painters in a less scattered way.

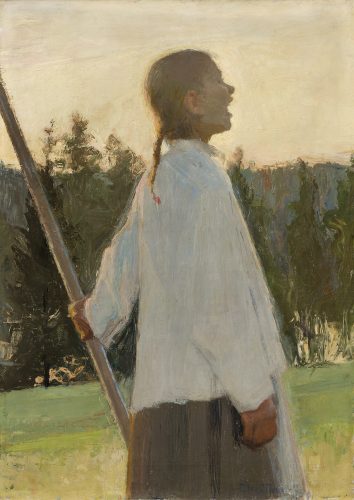

Ellen Thesleff, “Echo,” 1891. Anders Wiklöf Collection, Andersudde, Åland Islands. Photo: Kjell Söderlund.

What remains in my mind, apart from the opening portraits, are the realist paintings of working class women doing laundry or attending church, and personalized landscapes by Nordic artists such as the 1890 eerie lake landscape “Stokkavannet” by Norwegian Kitty Kielland; “Beach Parasol,” a painting of the artist at work on a beach in Brittany by Swedish Emma Lowstadt-Chadwick, and Finnish Ellen Thesleff’s “Echo,” a painting of a young peasant girl in a field experimenting with the sound of her voice. That image serves as the cover for the beautiful catalogue for Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900.

There are several other outstanding paintings and painters that could be described here, but I urge you to see this unusual exhibit for yourselves.

The Clark offers daily gallery talks through August 31, at 3:30 p.m.

Helen Epstein has been reviewing for artsfuse.org since 2010. She is the author of Joe Papp: An American Life, Music Talks, and other books about theater and the arts. You can find all her books at plunkettlakepress.com

Tagged: Clark Art Institute, Culture Vulture, Ellen Thesleff, Hannah (Hirsch) Pauli, Helen Epstein, Mary Cassatt

This article is SO interesting: my grandmother, a painter about whose many art colony residences I wrote in my just out Creative Gatherings: Meeting Places of Modernism (Reaktion Books, distributed by Chicago University Press), always took me to see Rosa Bonheur’s paintings in the Met Museum in New York, and she herself went to the Academie Julian, the basis for my book. AND the Swedish art students were so many in the small town of Grez-sur-Loing (where Robert Vonnoh painted and many US painters) that Sweden took over the main building and art studios there! THANKS!