Film Review: Director Bill Gunn — Two Restored Gems at the MFA

A chance to see two important works by pioneering African-American filmmaker Bill Gunn.

A scene from director Bill Gunn’s “Personal Problems,” screening at the Museum of Fine Arts.

By Peg Aloi

Boston filmgoers may be familiar with Ganga & Hess; I first saw it presented at a winter program curated by local filmmaker and academic John Gianvito, who also screened the film during his tenure as Head Curator at the Harvard Film Archive. It is being presented in a newly restored version at the Museum of Fine Arts for one night only (June 13th), in the company of a longer program (playing through June 14th) featuring a newly uncovered work by filmmaker Bill Gunn: Personal Problems, made for public television to be aired in 1980, but ultimately unreleased and, until now, largely unseen.

Personal Problems was conceived as a collaboration between two pioneering black artists who experimented with portraying the black experience in America. Writer Ishmael Reed and director Bill Gunn set and filmed this ensemble dramatic series in Harlem. The central character, Johnnie Mae Brown, is played by Vertamae Grosvenor (later Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor), an anthropologist who specialized in food culture (particularly of the Gullah community in South Carolina) and was a frequent commentator on NPR. She held memorable dinner parties with guest lists that were a who’s who of black American artists: James Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, and Maya Angelou. A noted singer and designer, her work as an actress also included roles in the recently-restored and re-released Julie Dash film Daughters of the Dust and Beloved. As Johnnie Mae, a hardworking nurse at Harlem Hospital who also writes poetry, Grosvenor is earthy and natural. She takes scenes of violence and stress at work in stride, but when her domestic situation becomes untenable (her husband Charles is unfaithful and her half-brother and sister arrive unexpectedly, causing chaos) she lets loose with a rant cataloguing her frustration with being everyone’s caretaker.

We learn about Johnnie Mae’s life by watching her live it. But there are also brief snippets of personal interviews with an unseen questioner. She speaks of missing her home (South Carolina) and of the difficulty of leaving work behind at day’s end. There is a sturdy naturalistic quality that results in a profound intimacy in the portrayal of the characters’ lives. One rollicking scene gives us Johnnie Mae with two friends at an outdoor wine bar, drinking chablis as they discuss clothes, dating, men, and their families. Johnnie Mae hints to her friends that she has started seeing a musician (played by Ishmael Reed), who is charmed by her poetry and impressed with her gusto for life. But, in the second part of the 165 minute long narrative, the pair run into problems. Johnnie Mae’s desire for a happier, more peaceful life remains elusive. The series has its cringeworthy moments (as when a white man, burning with political fervor, holds forth at a party about exploitation of the working class to a black man who doesn’t want to hear it), but the film’s power and honesty is rooted in a rough-edged realism — as well as its eagerness to utilize the then-fledgling form of video storytelling.

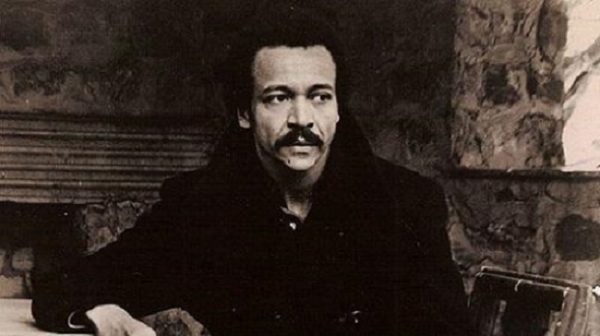

Director Bill Gunn — an experimental voice in portraying the African-American experience.

The Museum of Modern Art restoration of 1973’s Ganga & Hess, Gunn’s iconic experimental work, offers viewers a rare opportunity to see the film uncut (a mutilated version, which reduced its original 110 minutes to 78, was renamed Blood Couple and released on VHS; the director wanted no part of it). Ostensibly a horror film, but with an odd tone that merges humor, religion, and African-American cultural themes, the film nods to the blaxploitation cinema of the ’70s. By casting its star Duane Jones as Dr. Hess Green, the movie also tips its hat to the racially-charged George Romero debut Night of the Living Dead (1968). Hess is described in the film’s opening titles as an anthropologist who has been stabbed three times (a reference to the Christian trinity). The man now has an addiction to blood and he cannot die. His friend George (played by Gunn in a powerful cameo), who knows his secret, comes to visit and dies in Hess’s presence. When George’s self-centered, materialistic wife Ganga (Marlene Clark) comes to find her husband (annoyed he has not left her any money), she makes a play for Hess. The two immediately become lovers and Ganga learns, rather unexpectedly, that she is a widow. She embraces her new existence, however, eventually marrying Hess in a private ceremony. She becomes addicted to blood and immortal, as he is.

The word “vampire” is never uttered and it would be a disservice to the film to place it within the parameters of this narrow supernatural genre. Still, this is surely a vampire story. Ganga & Hess offers subtle, haunting layers of intrigue and narrative density, thanks to its unusual dramatic structure as well as its music and iconography, which overlay a European storyline with African mythology. In 2014 it was remade, rather lovingly, by Spike Lee; retitled Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, the homage is often a shot for shot rendition of the original. Ganga & Hess is an important work of contemporary cinema; an unusual film that is as beautiful as it is groundbreaking.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for The Boston Phoenix. She taught film and TV studies for ten years at Emerson College, and currently teaches at SUNY New Paltz. Her reviews also appear regularly online for The Orlando Weekly, Cinemazine, and Diabolique. Her long-running media blog “The Witching Hour” can be found at themediawitch.com